Palestine Pilgrims' Text Society.

THE

PILGRIMAGE OF S. SILVIA OF

AQUITANIA TO THE

HOLY PLACES

(CIRC. 385 A.D.),

Translated,

WITH INTRODUCTION AND NOTES,

BY

JOHN H. BERNARD, B.D.,

FELLOW OF TRINITY COLLEGE, DUBLIN, AND ARCHBISHOP KING'S LECTURER IN DIVINITY.

WITH

AN APPENDIX BY MAJOR-GENERAL SIR C. W. WILSON, R.E.

K.C.B., K.C.M.G., F.R.S., D.C.L., LL.D.

LONDON:

24,

HANOVER SQUARE, W.

1896.

CONTENTS.

| PAGE | |

| INTRODUCTION | 3 |

| PILGRIMAGE OF S. SILVIA OF AQUITANIA TO THE HOLY PLACES | 11 |

| S. SILVIAE AQUITANAE PEREGRINATIO AD LOCA SANCTA | 79 |

| APPENDIX | 137 |

ILLUSTRATIONS.

| PLAN OF CONSTANTINE'S CHURCHES AT JERUSALEM | 136 |

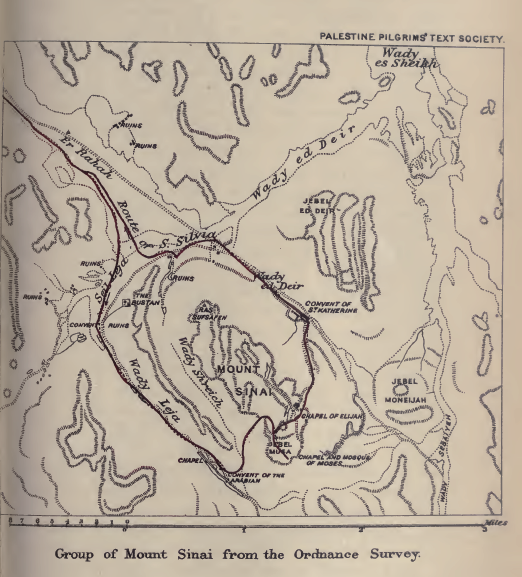

| GROUP OF MOUNT SINAI | 140 |

| MAP TO ILLUSTRATE THE ROUTE OF S. SILVIA | End |

THE PILGRIMAGE OF S. SILVIA

(CIRCA

385

A.D.).

INTRODUCTION.

THE MS. from which we derive our knowledge of the 'Pilgrimage of S. Silvia,' now for the first time translated into English, was discovered in 1883 at Arezzo, in Tuscany, by Signor G. F. Gamurrini, the learned librarian of a lay-brotherhood established in that place. He published an account of his discovery in Studi e Documenti di Storia e Diritto (1884), and in 1887 issued a volume containing the text of the MS., with introduction, facsimiles, and notes. The MS. is said to be written in an eleventh-century hand, and Gamurrini considers it tolerably certain that it was the work of a monk at Monte Casino. It is mutilated in several places, but contains a portion of the lost treatise, De Mysteriis, by S. Hilary of Poitiers, and two hymns, as well as the account of a journey to the Holy Land made by a female pilgrim. It is with this latter that we are here concerned.

The date of the pilgrimage can be fixed within a very few years, as Gamurrini and others1 have shown. The arguments upon which reliance may be placed are briefly as follows:

1°. In the account given of the services held at Jerusalem throughout the year, we have frequent mention of the great Church of the Resurrection, built by Constantine; and we also have an allusion (p. 44) to the Church of the Apostles at Constantinople, completed by the same emperor in 337 A.D. On the other hand, there is no mention of the churches of S. Stephen and S. Maria, which were built in Jerusalem in the fifth century, before which date, therefore, we must suppose the pilgrimage to have been undertaken.

2°. On the pilgrim's visit to Charræ she made inquiries of the bishop of that place as to the possibility of extending her journey inland, upon which he replied (p. 41): 'Hinc usque ad Nisibin mansiones sunt quinque; et inde usque ad Hur, quæ fuit civitas Chaldæorum, aliæ mansiones sunt quinque: sed modo ibi accessus Romanorum non est; totum enim illud Persæ tenent.' Now, Nisibis, which had been taken by Lucullus in 72 B.C., was restored to the Persians by Jovian in 363 A.D. This probably took place not long before the pilgrim's visit, as she is not aware of the cession having been made. The bishop's words ('modo ibi accessus,' etc.) also indicate that the transfer of territory had been recently brought about; but, in any case, we may conclude that the date of the pilgrimage is later (and probably not very much later) than 363 A.D.

3°. The pilgrim saw the church of S. Thomas at Edessa (p. 35), which she describes as 'nova dispositione.' Now, it was finished under Valens in 372 A.D.2

4°. Further, her visit to Edessa was apparently made during a period of tranquillity; there is no mention of the persecution of the Catholics by the Arians under the sanction of Valens. Gamurrini therefore suggests that she was there at a time when peace had been restored to the church after Valens' death in 378 A.D.

5°. On the other hand, she speaks of the 'martyrium' of S. Thomas as if it were distinct from the church. Hence her visit must have been prior to the translation of the tomb of S. Thomas to the new church, which took place in 394, under Bishop Cyrus.3

6°. The bishops of Bathnæ (p. 35), Edessa (p. 35), and Charræ (p. 38), are described as confessors. This, in all probability, refers to the persecution under Valens, who put all the Catholic bishops out of their sees. Now, Eulogius, Bishop of Edessa, died in 387-388, and was succeeded by Cyrus, who, as far as we know, and as is probable from the character of Theodosius and Arcadius, did not undergo persecution, and therefore was not a confessor. Accordingly, the bishop whom the pilgrim saw would be Eulogius, and this would fix her visit to Edessa as prior to 389 A.D.4

We conclude from these indications that the date of the pilgrimage is from 379 to 388 A.D. We now go on to determine the nationality and rank of the pilgrim.

Latin was her native tongue, although she understood at least a little Greek, sufficient to explain Greek words and phrases to the members of the sisterhood for whose benefit she writes. Thus the priest showing her the garden of S. John the Baptist at Enon (p. 31), describes it in Greek as κῆπος τοῦ ἀγίου ᾿ΙωάΝΝου, and then adds: 'Id est quod dicitis Latine hortus sancti Johannis.' Again (p. 46), speaking of the evening service, called at Jerusalem λυχΝικόΝ, she explains 'nam nos dicimus lucernare,' and notes that at this service the choir boys respond 'Kyrie eleison' instead of the familiar 'Miserere Domine,' etc.

Again, her comparison of the Euphrates (p. 34) with the Rhone implies that the writer is, and expects her readers to be, familiar with the latter river; hence, probably, the community to whom the account is addressed lived in the neighbourhood of the Rhone. With this, too, would well agree the words of the Bishop of Edessa, that she had come 'de extremis terris ad hæc loca' (p. 35).

And on examination of the linguistic peculiarities of the narrative the same conclusion emerges. The words perdicere, peraccedere, consuetudinarius; the use of eo quod instead of the acc. with infin. after verbs of narration; the use of quod in the sense of quando; and the use of ad for iu in such phrases as 'profecta sum de Antiochia ad Mesopotamiam' (p. 34); all point to the dialect of the south-west of France, and agree generally with the phraseology of Prosper of Aquitania. For a full discussion of these details the reader is referred to the special articles by Wölfflin and Geyer.5 What has been said is sufficient to justify the statement that our author came from Gaul, very possibly by the same route as that taken by the Pilgrim of Bordeaux. But she was not an ordinary pilgrim; she seems to have been a personage of considerable importance. She was courteously received wherever she went, and had interviews with the bishops and leading clergy of all the holy places. She had a guard of soldiers when proceeding from Sinai to Egypt through a disturbed and dangerous country (p. 20). Who, then, was she? This question cannot be answered with the same confidence as those with which we have been hitherto concerned. Kohler suggested that she might be identified with Galla Placidia, daughter of Theodosius the Great. This princess was at Constantinople in 423, and, according to a tradition related in an office of the Church of Ancona, went to Jerusalem afterwards. But, apart from the untrustworthiness of this tradition, the date which we must assign to our author's journey is at least forty years prior to that of Placidia, so that Kohler's guess need not detain us. Gamurrini, however, has made a much more plausible suggestion, namely, that the pilgrim whose account we have before us is S. Silvia of Aquitania, a sister of Rufinus, Prefect of the East under Theodosius the Great, of whose journey from Jerusalem to Egypt there is a notice in the Historia Lausiaca of Palladius. Like our author, S. Silvia was an earnest student of Scripture; the date of her journey, her rank and nationality, as also the fact that she rested at Constantinople for awhile on her return from Palestine, correspond well with our pilgrim's account – so well, indeed, that, in the absence of a better conjecture, and for convenience of reference, we have adopted provisionally Gamurrini's title: 'S. Silviæ Peregrinatio ad Loca Sancta.' But it should be pointed out that, while S. Silvia was an ascetic of a very severe and uncleanly type, there is no trace of asceticism in the conduct or language of our author.6 She looks with veneration on the ascetics whom she meets in her travels, but does not betray any tendency to follow in their steps. She grumbles much over the steepness of Mount Sinai (p. 13), and seems to regret that she cannot be carried up in a chair (in sella); while she saves herself a great deal of fatigue by riding on an ass up the slopes of Mount Nebo (p. 27) instead of walking on foot, as a genuine ascetic would have done. S. Silvia, on the other hand, boasts that she has never used a litter in her life.7

Whether our pilgrim be S. Silvia of Aquitania or not, there is no doubt as to the value of the story of her travels. It throws much light on many obscure topographical points, some of which have been discussed in the notes which follow.8 It opens up a large field for philological inquiry, as the Latin is peculiar. And last, but not least, it gives us a most interesting picture of the ritual of the Church at Jerusalem towards the close of the fourth century. We are informed that the Lenten fast was continued for eight weeks (p. 52), a hitherto unknown usage; and we find in the narrative the earliest notices extant of the use of incense in Christian worship (p. 48), of the festivals of the Purification of the Blessed Virgin (p. 51) and of Palm Sunday (p. 58), and of the custom of reciting three psalms at the canonical hours (p. 48). We also gather that the Kyrie Eleison had not yet found its way into the Gallican offices (p. 46), and that the custom of adapting the choice of psalms to the various seasons was unknown in Gaul at the date of our account (p. 76). All these are materials full of interest to the liturgiologist.9

The student of the Old Latin Versions of the Bible will find here several passages preserved, some of which were not hitherto known.10 Gamurrini has pointed out that the text of this MS. seems to have been largely made use of by Peter the Deacon, a librarian of Monte Casino in the twelfth century. His tract, De Locis Sanctis, is printed by Gamurrini as an appendix to the editio princeps of S. Silvia, and we hence see that the account given by our pilgrim of Mount Sinai and its neighbourhood was incorporated almost entire in Peter's treatise. However, Gamurrini's attempt to distinguish all the passages in the tract which are due to S. Silvia from those which bear traces of having been borrowed from Bede's work on the Holy Places is not very satisfactory; such discrimination is at best but guesswork.

In the Latin text appended to this translation, MS. readings have always been followed, except when the divergence is marked by footnotes. Gamurrini's second edition11 is much more accurate than the editio princeps, but cannot be used without caution, as his readings have been questioned in several instances by those who have personally inspected the MS. It is only necessary to add that the translation aims rather at being literal than elegant; S. Silvia, or whoever our pilgrim was, really does not deserve to be put into good English, as her Latin is very slipshod and tedious.

JOHN H. BERNARD.

TRINITY COLLEGE, DUBLIN,

November, 1890.

THE

PILGRIMAGE OF S. SILVIA OF AQUITANIA

TO THE HOLY PLACES.

[Sinai.]12 .... were shown according to the Scriptures.13 Meanwhile, as we walked, we arrived at a certain place, where the mountains between which we were passing opened themselves out and formed a great valley, very flat and extremely beautiful; and beyond the valley appeared Sinai, the holy Mount of God. This spot where the mountains opened themselves out is united with the place where are the Graves of Lust.14 And when we came there those holy guides, who were with us, bade us, saying: 'It is a custom that prayer be offered by those who come hither, when first from this place the Mount of God is seen.' So then did we. Now, from thence to the Mount of God is perhaps four miles altogether through that valley which I have described as great.

For that valley15 is very great indeed, lying under the side of the Mount of God; it is perhaps – as far as we could judge from looking at it and as they told us – sixteen miles in length. In breadth they called it four miles. We had to cross this valley in order to arrive at the mount. This is that same great and flat valley in which the children of Israel waited during the days when holy Moses went up into the Mount of God, where he was for forty days and forty nights. This is the valley in which the calf was made; the spot is shown to this day, for a great stone stands fixed in the very place. This, then, is the valley at the head of which was the place where holy Moses was when he fed the flocks of his father-in-law, where God spake to him from the Burning Bush.16 Now, our route was first to ascend the Mount of God at the side from which we were approaching, because the ascent here was easier; and then to descend to the head of the valley where the Bush was, this being the easier way of descent from the Mount of God. And so it seemed good to us that having seen all things which we desired, descending from the Mount of God, we should come to where the Bush is, and thence retrace our way through the middle of the valley, throughout its length, with the men of God, who showed us each place in the valley mentioned in Scripture.

So then we did. Then, going from that place where we had offered up prayer as we came from Faran, our route was to cross through the middle of the head of the valley, and so wind round to the Mount of God. The mountain itself seems to be single, in the form of a ring; but when you enter the ring [you see that] there are several, the whole range being called the Mount of God. That special one at whose summit is the place where the majesty of God descended, as it is written, is in the centre of all. And although all which form the ring are so lofty as I think I never saw before, yet that central one on which the majesty of God descended is so much higher than the others, that when we had arrived at it, all those mountains which we had previously thought lofty were below us as if they were very little hills. And this is truly an admirable thing, and, as I think, not without the grace of God, that although that central one specially called Sinai, on which the majesty of God descended, is higher than all the others, yet it cannot be seen until you come to its very foot, though before you actually are on it. For after you have accomplished your purpose, and have descended, you see it from the other side, which you could not do before you are on it. This I learnt from the report of the brethren before we arrived at the Mount of God, and after I had arrived there I perceived it to be so for myself.

It was late on the Sabbath17 when we came to the mountain, and arriving at a certain monastery, the kindly monks who lived there entertained us, showing us all kindliness; for there is a church there with a priest. There we stayed that night, and then early on the Lord's day we began to ascend the mountains one by one with the priest and the monks who lived there. These mountains are ascended with infinite labour, because you do not go up gradually by a spiral path (as we say, 'like a snail shell'), but you go straight up as if up the face of a wall, and you must go straight down each mountain until you arrive at the foot of that central one which is strictly called Sinai. And so, Christ our God commanding us, we were encouraged by the prayers of the holy men who accompanied us; and although the labour was great – for I had to ascend on foot, because the ascent could not be made in a chair – yet I did not feel it. To that extent the labour was not felt, because I saw that the desire which I had was being fulfilled by the command of God. At the fourth hour we arrived at that peak of Sinai, the holy Mount of God, where the law was given, i.e., at that place where the majesty of God descended on the day when the mountain smoked.18 In that place there is now a church – not a large one, because the place itself, the summit of the mountain, is not large; but the church has in itself a large measure of grace.

When therefore, by God's command, we had arrived at the summit, and come to the door of the church, the priest who was appointed to the church, coming out of his cell, met us, a blameless old man, a monk from early youth, and (as they say here) an ascetic; in short, a man quite worthy of the place. The other priests met us also, as well as all the monks who lived there by the mountain; that is, all of them who were not prevented by age or infirmity. But on the very summit of the central mountain no one lives permanently; nothing is there but the church and the cave where holy Moses was.19 Here the whole passage having been read from the book of Moses, and the oblation made in due order, we communicated; and as I was passing out of the church the priests gave us gifts of blessing20 from the place; that is, gifts of the fruits grown in the mountain. For although the holy mount of Sinai itself is all rocky, so that it has not a bush on it, yet down near the foot of the mountains – either the central one or those which form the ring – there is a little plot of ground; here the holy monks diligently plant shrubs and lay out orchards and fields; and hard by they place their own cells, so that they may get, as if from the soil of the mountain itself, some fruit which they may seem to have cultivated with their own hands. So, then, after we had communicated and the holy men had given us these gifts of blessing, and we had come out of the door of the church, I began to ask them to show us the several localities. Thereupon the holy men deigned to show us each place. For they showed us the famous cave where holy Moses was when for the second time he went up to the Mount of God to receive the tables [of the law] again after he had broken the first on account of the sin of the people; and the other places also which we desired to see or which they knew better they deigned to show us. But I would have you to know, ladies, venerable sisters, that from the place where we were standing – that is, in the enclosure of the church wall, on the summit of the central mountain – those mountains which we had at first ascended with difficulty were like little hills in comparison with that central one on which we were standing. And yet they were so enormous that I should think I had never seen higher, did not this central one overtop them by so much. Egypt and Palestine and the Red Sea and the Parthenian Sea,21 which leads to Alexandria, also the boundless territories of the Saracens, we saw below us, hard though it is to believe22 all which things those holy men pointed out to us.

[Horeb.] Having satisfied every desire with which we had made haste to ascend, we began now to descend from the summit of the Mount of God to another mountain which is joined to it; the place is called Horeb, and there is a church there. This is that Horeb where was the holy prophet Elijah when he fled from the face of King Ahab, where God spake to him saying, 'What doest thou here, Elijah?'23 as it is written in the books of Kings. For the cave where holy Elijah hid is shown to this day before the door of the church which is there; the stone altar is also shown which holy Elijah built that he might offer sacrifice to God. All which things the holy men deigned to show us. There we offered an oblation and an earnest prayer, and the passage from the book of Kings was read; for we always especially desired that when we came to any place the corresponding passage from the book should be read. There having made an oblation, we went on to another place not far off, which the priests and monks pointed out, viz., that place where holy Aaron had stood with the seventy elders when holy Moses received from the Lord the law for the children of Israel.24 There, although the place is not roofed in, there is a huge rock having a circular flat surface on which, it is said, these holy persons stood. And in the middle there is a sort of altar made with stones. The passage from the book of Moses was read, and one psalm said which was appropriate to the place; and then, having offered a prayer, we descended.

[The Bush.] Now, it began to be about the eighth hour, and we had yet three miles to go before we should have gone through the mountains we had entered upon late the day before; but we had to go out at a different side from that by which we had entered, as I said above, because it was necessary to walk over all the holy places and to see the cells that were there, and so to go out at the head of that above-mentioned valley lying under the Mount of God. It was furthermore necessary to go out at the head of the valley, because there were there many cells of holy men and a church where the Bush is; this bush is alive to the present day, and sends forth shoots. So having descended the Mount of God, we arrived at the Bush about the tenth hour. This is the Bush I spoke of above, from which God spake to Moses in the fire, which is in the place where there are many cells and the church at the head of the valley. Before the church there is a very pleasant garden with abundance of good water, in which garden the Bush is. The place is shown near where holy Moses stood when God said to him, 'Loose the latchet of thy shoe,'25 etc. When we came to this place it was the tenth hour, and because it was so late we could not make an oblation; but prayer was offered in the church, and also in the garden at the Bush; also the passage was read from the book of Moses as usual, and so, as it was late, we took a light meal there in the garden before the Bush with the holy men. So there we stayed, and rising early on the next day, we asked the priests that the oblation should be made, which was done accordingly.

Now, our way was to go through that central valley, throughout its length, i.e., the valley where, as I said before, the children of Israel stayed while Moses ascended and descended the Mount of God. The holy men used to show us each place as we came to it throughout the valley. For at the first head of the valley where we had halted we had seen the Bush from which God spake to holy Moses in the fire; we had also seen the place where holy Moses stood before the Bush, where God said to him: 'Loose the latchet of thy shoe, for the place whereon thou standest is holy ground.' And so also they began to show us the other places as we came to them from the Bush. For they pointed out the place where the camp of the children of Israel was during the days that Moses was in the mount. They also pointed out the place where the calf was made; a great stone is fixed in that place to this day. As we went we saw from the opposite side the summit of the mountain, which looks down over the whole valley; from which place holy Moses saw the children of Israel dancing at the time when they made the calf.26 They also showed a huge rock at the place where holy Moses descended with Joshua, the son of Nun, on which rock he, being angry, brake the tables which he was carrying. They also showed their dwelling-places throughout the valley, of which the foundations appear to this day, of circular form, made with stone: they also showed the place where holy Moses, when he returned from the Mount, bade the children of Israel run 'from gate to gate.'27 They also showed the place where the calf which Aaron had made for them was burnt at the command of holy Moses. They also showed the stream of which holy Moses made the children of Israel to drink, as it is written in the book of Exodus.28 They also showed us the place where the seventy men received of the spirit of Moses.29 And they showed us the place where the children of Israel lusted for food. [Taberah.] They showed us also that place called the Place of Burning, because a part of the camp was burned, the fire abating at the prayer of holy Moses.30 They showed also that place where it rained manna and quails. In fine, everything recorded in the holy books of Moses as having been done in that place, to wit, the valley which I said lies under the Mount of God, holy Sinai, was shown to us; of all which things it is superfluous to write in detail, not only because such great things could not be retained [in the memory], but because when it pleases you to read the holy books of Moses you will see more quickly all the things that were there done.

But, as I was saying, this is the valley where the Passover was celebrated, the first year being completed of the journeying of the children of Israel from the land of Egypt; for in that valley Israel tarried for a space while holy Moses went up to the Mount of God and came down a first and second and final time. There they tarried until the tabernacle should be made, and all things which were shown him in the Mount of God. For the place was shown to us where Moses at the first constructed the tabernacle, and the several things were finished which God had commanded Moses in the Mount that they should be done. We saw also in the far end of the valley the Graves of Lust,31 at that spot where we came back again to our road; i.e., where, going out of the great valley, we re-entered the path between the mountains above mentioned by which we had come. On that day we met with those other very holy monks who, by reason of age or infirmity, were unable to be present in the Mount of God to make an oblation; however, they deigned to receive us very kindly when we arrived at their cells. So we saw all the holy places which we desired, and also all the places which the children of Israel had touched in going to or returning from the Mount of God; and having also seen the holy men who lived there in the name of God, we returned to Faran. And although I ought always to thank God in everything (not to speak of these so great benefits which He has vouchsafed to confer on me, unworthy and undeserving, that I should walk through all these places, benefits unmerited indeed), yet I am not even able sufficiently to thank all those holy men who deigned with willing mind to receive my insignificant self in their monasteries, or to guide me through all the places which I was always seeking in accordance with the Holy Scriptures. Many indeed of these holy men who lived in or round about the Mount of God deigned to guide us back to Faran; they were, however, of stronger frame.

[Faran.] Now, when we had arrived at Faran, which is distant thirty-five miles from the Mount of God, we had to stay there two days to recruit our strength. Then rising early on the third day, we came at length to the station – that is, to the desert of Faran – where we had halted on our way [to Sinai], as I said above. Thence on the next day making a circuit, and going yet a little way between the mountains, we arrived at the station which is over the sea – i.e. in the place where there is an exit from among the mountains, and the path begins to be quite near the sea; near the sea to this extent, that at one moment the waves come up to the feet of the animals, and at another moment the path through the desert is 100, 200, or sometimes more than 500, paces from the sea: the road there is not inland, but the deserts are quite sandy. The people of Faran, who were accustomed to travel about there with their camels, place landmarks here and there, and, attending to these, they march by day. At night the camels take note of them. In short, the people of Faran from habit travel by night in that place more quickly and surely than other men could travel on a highroad. So on our return journey we came out from among the mountains at that spot where we had entered originally, and thus we wound round to the sea. The children of Israel also, returning to Sinai, the Mount of God, returned by the way that they had gone to that very place where we came out from among the mountains, and finally approached the Red Sea. Thence our return journey was by the route that we had taken going; and the children of Israel made their march from the very same place, as it is written in the books of holy Moses.32 [Clesma.] We returned to Clesma33 by the same route and the same stations which we had gone by: when we got to Clesma we had to recruit for a while, for we had stoutly made our way through the sandy soil of the desert.

[Goshen.] Now, although I already had seen the land of Goshen when I was in Egypt the first time, yet [I wished] to explore all the places which the children of Israel as they came forth from Rameses had touched on their journey until they arrived at the Red Sea; the place is now called Clesma, from the fort that is there. So I desired to go from Clesma to the land of Goshen – i.e., to the city called Arabia (which city is in the land of Goshen). From it the territory itself derives its name, viz., the land of Arabia, the land of Goshen,34 which is part of the land of Egypt, though it is a good deal better than the rest of Egypt. From Clesma – i.e., from the Red Sea – to the city of Arabia there are four desert stations; so far desert, however, that at the stations there are cells with soldiers and officers, who used always to conduct us from fort to fort. On that journey the holy men who were with us – i.e., the clergy and monks – used to show us the several places which I was always seeking out in accordance with the Scriptures. Some were on the right, some on the left of our path; some at a distance from our course, others near. For I trust that you of your good will will credit me when I say that, as far as I could see, the children of Israel journeyed in such a way that, whatever distance they went to the right, that they returned to the left. As far as they went forward, so far used they again to return backward; and so they made their journey until they arrived at the Red Sea.

[Pi-hahiroth.] For Epauleum35 was shown to us, though from the opposite side, and we were at Migdol. [Migdol.] There is now a fort there, with an officer commanding the soldiery in accordance with Roman discipline. [Baalzephon.] According to custom, they guided us thence to another fort, and Belsefon36 was shown to us: we were there too. It is a plain above the Red Sea near the side of the mountain I mentioned above, where the children of Israel cried out when they saw the Egyptians coming after them.37 [Etham.] Oton,38 too, was shown to us, which is near the wilderness, as it is written, and also Succoth. [Succoth.] Succoth is a low hill in the midst of a valley, near which little hill the children of Israel encamped. For this is the place where the law of the Passover was received.39 [Pithom.] The city of Pithom, which the children of Israel built,40 was shown to us on the same journey. At the spot where we entered the borders of Egypt, leaving behind us the territories of the Saracens, that same Pithom is now a fort. [Heröopolis.] Heroöpolis, which was a city at the time when Joseph met Jacob his father as he came, as it is written in the book of Genesis,41 is now a mere κώμη, but a large one, what we call a village. This village has a church and martyr memorials and many cells of holy monks: to see each of which we had to descend, after the custom which we had adopted. This village is now called Hero, which Hero is at the sixteenth milestone from the land of Goshen. The place is within the borders of Egypt, and is tolerably large: a certain part of the river Nile runs by it. [The city of Arabia.] And so coming out from Hero, we arrived at the city which is called Arabia,42 a city in the land of Goshen, as it is written that Pharaoh said to Joseph: 'In the best of the land of Egypt make thy father and brethren to dwell, in the land of Goshen, in the land of Arabia.'43

[Rameses.] Four miles from the city of Arabia is Rameses. But in order to come to the station of Arabia we passed through the midst of Rameses, which latter city is now a bare field without a single habitation. It is quite plain that it was once a great city, built in a circular form, and had many buildings; its ruins just as they fell are visible in great numbers to this day. But there is nothing else there now except one great Theban stone,44 in which two great statues are cut out, which they say are statues of holy men, even Moses and Aaron, erected in their honour by the children of Israel. And there is, moreover, a sycamore-tree, which they say was planted by the patriarchs;45 for it is very old, and consequently very small, although it even yet bears fruit. Now, whoever has any ailment, they go there and pluck off twigs, and it serves them: this we learnt from the report of the holy Bishop of Arabia. He told us that the name of the tree, as they call it in Greek, was δέΝδρος ἀληθείας – as we say, the Tree of Truth. This holy bishop deigned to meet us at Rameses. He is an elderly man, truly devout, as becomes a monk, courteous, enter- taining strangers kindly, well versed in the Scriptures of God. He then put himself to the trouble of meeting us, and showed us everything, telling us about the statue which I have mentioned, and also about the sycamore-tree. This holy bishop also told us how that Pharaoh, when he saw that the children of Israel had escaped him, before he tried to catch them, had gone with his whole army into Rameses, and had burnt it completely, because it was very great, and thence had set out after the children of Israel.

Now, by chance it very happily fell out that the day on which we came to the station of Arabia was the eve of the most blessed day of the Epiphany.46 On that day vigils were to be held in the church. And so the holy bishop kept us there for some two days, a holy man, and in truth a man of God, known to me well from the time that I was in the Thebaid. This holy bishop was formerly a monk; he was brought up from a child in a cell, and was so versed in the Scriptures, and so disciplined in his whole manner of life, as I have said above. From here we sent back the soldiers who, according to the Roman military system, had given us protection as long as we walked through suspected places. But now, since the line of our route throughout Egypt was by the public road, which crossed it through the city of Arabia – i.e., which leads from the Thebaid to Pelusium – it was no longer necessary to trouble the soldiers. Proceeding thence right through the land of Goshen, we pursued our journey continually through vineyards and balsam plantations and orchards and tilled fields and gardens; at first keeping quite above the bank of the river Nile, through frequent estates which once were the farms of the children of Israel. In short, I think I never saw a fairer territory than the land of Goshen. [Taphnis.] So journeying from the city of Arabia for two days right through the land of Goshen, we arrived at Taphnis, 47 the city where holy Moses was born. This is that city of Taphnis which was once Pharaoh's metropolis.. And although I already had seen these places, as I said above, when I was at Alexandria or in the Thebaid, yet I wished to learn fully all about the places which the children of Israel had traversed as they marched from Rameses to Sinai, the holy Mount of God; and so it was necessary to return again to the land of Goshen, and thence to Taphnis. [Pelusium.] Marching from Taphnis, walking along a known route, I arrived at Pelusium; and marching thence, again making our route through the several stations in Egypt by which we had formerly taken our course, I arrived at the borders of Palestine; and thence in the name of Christ our God, again making my stations through Palestine, I returned to Ælia – that is, Jerusalem.

[Jerusalem.] Having spent some time there, God commanding me again, I had the wish to go as far as Arabia, to Mount Nebo, where God commanded Moses to go up, saying to him: 'Get thee up into the mountain Arabot, unto Mount Nebo, which is in the land of Moab, over against Jericho; and behold the land of Canaan, which I give unto the children of Israel for a possession: and die in the mount whither thou goest up.'48 And so Jesus our God, who will not fail those who trust in Him, vouchsafed to bring to effect this my wish. Starting from Jerusalem, and journeying with holy men, with the priest and deacons from Jerusalem, and some brethren – that is, monks – we arrived at that place of the Jordan where the children of Israel had crossed when holy Joshua, the son of Nun, made them cross the Jordan, as it is written in the book of Joshua.49 For the place was shown to us a little higher up where the children of Reuben and Gad and the half-tribe of Manasseh had made an altar at that part of the bank where Jericho is. [Livias.] Crossing the stream, we came to the city called Livias,50 which is in the plain where the children of Israel then encamped. For the foundations of the camp of the children of Israel and of the dwellings in which they abode appear there to this day.

The plain itself is very large, under the mountains of Arabia above Jordan. This is the place of which it is written: 'And the children of Israel wept for Moses in the plains of Moab and Jordan opposite Jericho forty days.'51 This is the place where, after the departure of Moses, Joshua the son of Nun was straightway filled with the spirit of knowledge. For Moses put his hands upon him, as it is written. This is the place where Moses wrote the book of Deuteronomy; here he spake in the ears of the whole congregation of Israel the words of his song, even to the end of that which is written in the book of Deuteronomy. Here holy Moses, the man of God, blessed the children of Israel separately in order before his death. And when we had come to this plain we went up to the very place, and there a prayer was offered, and a certain passage of Deuteronomy read at the spot, his song and the blessings with which he blessed the children of Israel. And after the reading, prayer was offered again, and, giving thanks to God, we moved on from thence. For it was always our custom that whenever we were enabled to approach the desired places, a prayer should first be offered, then the lection read from the book, then one appropriate psalm said, and, finally, another prayer. This custom we always held to, God commanding us, whenever we were able to arrive at the desired places. Then, that the work we had begun should be accomplished, we began to hasten in order that we might arrive at Mount Nebo. As we went the priest of the place, i.e., of Livias, whom we had persuaded to move with us from the station, because he knew the places better, gave us advice. And this priest said to us: If you wish to see the water which flowed out of the rock, which Moses gave to the children of Israel when they were athirst, you can see it if you like to impose on yourselves the fatigue of going52 about six miles out of your way. When he said this we eagerly wished to go, and immediately diverging from our road, we followed the priest who led us. In that place there is a little church under a mountain – not Nebo, but another inner mountain not far from Nebo; many truly holy monks live there, whom they here called ascetics.

These holy monks deigned to receive us very kindly; they permitted us to pay them a visit. When we had entered and had offered prayer with them, they deigned to give us gifts of blessing, which they are accustomed to give to those whom they receive kindly. But, as I was saying, in the midst there, between the church and the monastery, there flows out of a rock a great stream of water very fair and limpid, and with a very good taste. Then we asked the holy monks who lived there what was this water which was so good, and they told us that it was the water which holy Moses gave to the children of Israel in this wilderness. Then, according to custom, a prayer was offered there, and the lection read from the books of Moses, and one psalm was said; and so with those holy monks and clergy who had come with us we went out to the mountain. Many, too, of the holy monks that lived there near the water, who were able and willing to endure the fatigue, deigned to ascend Mount Nebo along with us. So then, starting from that place, we arrived at the foot of Mount Nebo, which, though very high, could yet be gone up for the most part sitting on an ass, but there was a bit slightly steeper which we had to go up laboriously on foot.

[Mount Nebo.] So we arrived at the summit of the mountain, where there is now a small church on the summit of Mount Nebo. Inside this church, at the place where the pulpit is, I saw a place slightly raised containing about as much space as is usual in a grave. I asked the holy men what this was, and they answered: 'Here holy Moses was laid by the angels, since, as it is written, "No man knows how he was buried,"53 since it is certain that he was buried by angels. For his grave where he was laid is now shown to-day; as it was shown to us by our ancestors who lived here, so do we point it out to you; our ancestors said that it was handed down to them as a tradition by their ancestors.' And so presently a prayer was offered, and all things which we were accustomed to do in order in the several sacred places were also done here, and then we began to go out of the church. Then those who knew the place, the priests and holy monks, said to us: 'If you wish to see the places written of in the book of Moses, go out of the door of the church, and from the very summit, but on the side from which you can be seen from here, behold and see;54 we shall tell you all the places which are visible.' At this we were delighted, and went out at once. [The Prospect from Mt. Nebo.] For from the door of the church we saw the place where the Jordan enters the Dead Sea, which place appeared below us as we stood. We saw also opposite, not only Livias, which was on the near side of Jordan, but Jericho which was beyond Jordan, so prominent was the lofty place where we stood before the door of the church. The most part of Palestine, the land of promise, was seen from thence, also the whole Jordan territory – that is, as far as our eyes could reach. On the left hand we saw all the lands of the Sodomites, and also Segor, which Segor55 is the only one remaining to-day of the famous five. There is a memorial of it, but of those other cities nothing appears save the overturned ruins, just as they were turned into ashes. The place where was the inscription about Lot's wife was shown to us, which place we read of in the Scriptures. But, believe me, venerable ladies, the pillar itself is not visible, only the place is shown. The pillar is said to be covered up in the Dead Sea. We certainly saw the place, but we saw no pillar; I cannot deceive you about this matter. The bishop of the place, that is, of Segor, told us that it is now some years since the pillar was visible. It is about six miles from Segor to the place where the pillar stood, which the water now covers. Also we went out on the right side of the church, and opposite were shown us two cities – Esebon,56 now called Exebon, which belonged to Seon, King of the Amorites; and another, now called Sasdra,57 of Og the King of Basan. From the same place was shown opposite to us Fogor,58 which was a city of the kingdom of Edom. All these cities which we saw were situated in the mountains. Underneath us the ground seemed to be somewhat flatter, and we were told that in the days when holy Moses and the children of Israel fought against these cities they encamped there; and the signs of a camp were there apparent. On the side of the mountain that I have called the left, which is over the Dead Sea, a very sharp mountain was shown to us, which before was called Agrispecula.59 This is the mountain where Balak the son of Beor placed Balaam the soothsayer to curse the children of Israel, and God would not allow him, as it is written. And so having seen all things which we desired, in the name of God, returning through Jericho, we retraced to Jerusalem the whole route by which we had come.

[Ausitis.] After some time I wished to go also to the region of Ausitis,60 to visit the grave of holy Job for the sake of prayer. For I used to see many holy monks coming from thence to Jerusalem to visit the holy places for the sake of prayer, who, reporting particulars about those places, made me desirous to impose on myself the labour of visiting them, if, indeed, that can be called labour when a man sees that his desire is being accomplished. So I set out from Jerusalem with the holy men, who deigned to accompany me on my journey, they also going for the sake of prayer. Taking our way from Jerusalem to Carneas, we passed through eight stations. (The city of Job is now called Carneas, formerly being called Dennaba,61 in the land of Ausitis, in the borders of Idumæa and Arabia.) Going by this route, I saw above the bank of the river Jordan a very fair and pleasant valley, abounding with vines and trees, for many very good streams were there. [Salem.] In that valley there was a large village, which is now called Sedima. In that village, situated in the midst of the plain, in the centre there is a little hillock, made as tombs are accustomed to be, like a large tomb, and on the top is a church. Underneath, round the circumference of the little hill, great and ancient foundations appear. And also in the village itself some tombs still remain. When I saw this pleasant place, I inquired what it was, and I was told, This is the city of King Melchizedek, formerly called Salem, whence the present village, by corruption of the name, is called Sedima.62 The building which you see at the summit of that little hill, in the centre of the village, is a church, which church is now called in the Greek language Opu Melchisedech63 for there Melchizedek offered pure victims to God – that is, bread and wine, as it is written.

Forthwith when I heard these things we got down from our animals, and, behold, the holy priest of the place and the clergy deigned to meet us; and they, receiving us, led us straight up to the church. When we had got there, first, according to custom, a prayer was offered, then the passage was read from the book of holy Moses, and a psalm said appropriate to the place, and again having offered a prayer, we descended. When we had descended, the holy priest, an elderly man, and well versed in the Scriptures, who had presided over the place from the time that he was a monk, spoke to us, of whose life many bishops, as we learnt afterwards, bore high testimony. For they said of him that he was worthy to preside in the place where holy Melchizedek first offered pure victims to God as he met holy Abraham.

When we had descended, as I have said above, from the church, this holy priest said to us: 'Behold those foundations round that little hill which you see, they are [the remains] of the palace of Melchizedek. To this day, if anyone wishes to build a house near there, and happens on the foundations, he sometimes finds little pieces of silver and bronze. The way which you see crosses between the river Jordan, and that village is the way by which holy Abraham returned from the slaughter of Chedorlaomer,64 King of Nations, coming back to Sodom, where holy Melchizedek, King of Salem, met him.' Then, as I remembered, it was written65 that S. John baptized in Enon near Salem, I asked of him how far off that place was. And the holy priest said: 'It is about two hundred paces; if you like, I shall now lead you there on foot. This large and pure stream which you see in the village comes from that source.' So I began to thank him, and to ask him to lead us to the place, which he accordingly did. Straightway we began to go with him on foot through a most pleasant valley, until we arrived at a very pleasant fruit-garden, where he showed us in the midst a fountain of very good and pure water, for it sent forth all at once a new stream. This fountain had before it a sort of lake, where it appeared that S. John the Baptist had baptized. Then the holy priest said to us: 'To this day this garden is called by no other name in the Greek tongue than Copos tu agiu Johanni66 – that is, as you say in Latin, Hortus sancti Johannis – "The garden of S. John." For many brethren, holy monks, coming from different places, proceed to wash here.' Then at the fountain, as at every place, a prayer was offered, and the lection was read, an appropriate psalm was sung, and all things which we were accustomed to do when we came to holy places we also did there. And the holy priest told us that to the present day, always at Easter, those who were to be baptized in the village – i.e., in the church called Opu Melchisedech – were all baptized in this fountain; and they would return early to vespers with the clergy and monks, singing psalms or antiphons, and so all who had been baptized would early be led back from the fountain to the Church of S. Melchizedek. Receiving then from the priests gifts of blessing from the orchard of St. John the Baptist, and likewise from the holy monks who there had their cells in the fruit-garden itself, and always giving thanks to God, we set out on our way whither we were going.

Thence going for some time through the valley of the Jordan above the bank of the river, because that was our route for a time, we suddenly saw the city of the holy prophet Elijah – i.e., Thesbe, whence he has the name Elijah the Tishbite.67 And there to this day is the cave where the holy man sat, and there is the grave of holy Getha,68 whose name we read in the books of Judges. And so giving thanks to God, according to custom, we proceeded on our journey. As we went we saw a very pleasant valley on the left approaching us, which valley, being large sent a great torrent into the Jordan; and there in that valley we saw the cell of a certain brother – a nunnus, that is, a monk. Then I, as I am an inquisitive person, began to inquire what this valley was where the holy monk had made his cell, for I did not think it was without reason. Then the holy men who were travelling with me – that is, those who knew the place, said: 'This is the valley of the Cherith,69 where holy Elijah the Tishbite dwelt in the days of King Ahab, when there was a famine; and at the command of God the ravens used to bring him meat, and he drank water from the torrent. For this torrent, which you see flowing from the valley into the Jordan, is the Cherith.' And so giving thanks to God, who vouchsafed to show us, undeserving, those things which we desired, we began to go on our way as on the other days. And so going on our way, suddenly on our left, whence opposite to us we saw the parts of Phoenicia, there appeared a great and lofty mountain, which extended a great distance. . . .

[A leaf wanting]

[Carneas.] which holy monk and ascetic thought it necessary, after the many years which he had spent in the desert, to move himself and to descend to the city of Carneas, that he might bid the bishop and clergy of that time, as it had been revealed to him, to dig in the place which was shown him. This was done, and they, digging in the place which had been pointed out, found a cave, which they followed for about a hundred paces, when suddenly as they dug a stone became visible; and when they had uncovered this stone they found carved on its face the word Job. To this Job the church that you see was built in that place; so, however, that the stone with the body should not be moved, but that the body should be placed where it had been found, and should lie under the altar. That church, which some tribune built, stands, imperfect, to this day. The next morning we asked the bishop to offer the oblation, which he deigned to do, and the bishop giving us his blessing, we departed. Then communicating, and ever thanking God, we returned to Jerusalem, pursuing our journey through the several stations through which we had gone three years before.

[Jerusalem.] There, in the name of God, having spent some time, it being now three full years from the time that I had come to Jerusalem, and having seen all the holy places, to which for the sake of prayer I had directed my course, I had a mind to return to my own country. But I wished, God commanding me, to go to Mesopotamia in Syria to visit the holy monks, who were said to be numerous there, and of such blameless life as baffles description; and also for the sake of prayer at the martyr-memorial of S. Thomas the Apostle at Edessa, where his whole body is laid. For Jesus our God testified that, after He had ascended into heaven, He would send him there, in the letter70 which He sent to King Abgar by Ananias as courier, which letter is preserved with great reverence at the city of Edessa, where the martyr-memorial is. I would have you of your affection to believe that there is no Christian who does not wend his way thither for the sake of prayer, who has got as far as the holy places at Jerusalem; it is at the twenty-fifth station from Jerusalem. And since from Antioch it is nearer to Mesopotamia, it was very convenient for me, at the command of God, that, as I was returning to Constantinople, and my way was through Antioch, I should go from thence to Mesopotamia. This, then, I did at the command of God.

[Antioch.] So, in the name of Christ our God, I set out from Antioch to Mesopotamia, holding my way through the stations and some cities of the province of Cœle-Syria, i.e., Antioch; and thence I entered the borders of the province of Augustofratensis,71 [Hierapolis.] and arrived at the city of Gerapolis,72 which is the metropolis of that province, viz., of Augustofratensis. And as this city is very fair and rich, and abounds in everything, it was necessary for me to make a halt there, as the boundaries of Mesopotamia were not far off. [The Euphrates.] And then, starting from Hierapolis at the fifteenth milestone, in the name of God, I arrived at the river Euphrates, of which it is very well written73 that it is 'the great river Euphrates,' so mighty and, as it were, terrible is it, for it rushes down in a torrent like the river Rhone,74 except that the Euphrates is bigger. As we had to cross in ships, and in none but large ships, I waited there till mid-day was past, and then, in the name of God, I crossed the river Euphrates, and entered the borders of Mesopotamia in Syria. [Bathnæ.] So, again making my way through some stations, I came to a city whose name we read in the Scriptures – that is, Batanis75 – which survives to this day. It has a church, with a right holy bishop, monk, and confessor, and some martyr-memorials. It is a city swarming with inhabitants, for there is to be found the soldier with his tribune. [Edessa.] Again setting out from thence, we arrived, in the name of Christ our God, at Edessa; and when we had arrived, we straightway proceeded to the church and the martyr-memorial of S. Thomas.

There, according to our custom, prayers were offered; and we read there both the other things which we were in the habit of reading at the holy places, and also some things of S. Thomas himself. The church is great and very beautiful, and built in a new form,76 truly worthy to be the house of God; and as there were many things there which I desired to see, it was necessary for me to make a stay of three days. In that city I saw many martyr-memorials, also the holy monks who lived there – some at the martyr-memorials, others having cells in retired places at a distance from the city. And the holy bishop of the city, a truly devout man, a monk and confessor,77 receiving me kindly, said to me: 'As I see, daughter, that for the sake of religion you imposed this great toil on yourself to come from distant lands to these places, if you like we will show you whatever places here are pleasing for Christians to see.' Thereupon, first giving thanks to God, I besought him much that he would deign to do as he said. Accordingly he brought me first to the palace of King Abgar, and showed me there a great statue of him, very like (as they said), of marble, which shone as if it were of pearl. From the face of Abgar, it would appear that he was a wise and honourable man. Then said the holy bishop to me: 'See King Abgar, who, before he saw the Lord, believed that He was the Son of God.' And near was another statue made of like marble, which, he said, was that of his son Maanu; it also had something gracious in its look. Then we went into the inner part of the palace, and there were fountains full of fish such as I never saw before: of such size were they, so brilliant, and of such a good flavour. The city has no other water inside it but that which comes from the palace, which is like a great silver stream.

[The story of Abgar.] And then the holy bishop told me about that water, saying: 'Once on a time, after that King Abgar had written to the Lord, and the Lord had sent a reply to Abgar by Ananias the courier (as it is written in the letter itself), when some time had elapsed, the Persians came down and surrounded the city. But Abgar, bearing the letter of the Lord to the gate, prayed publicly with all his army. And he said78: "Lord Jesus, Thou hast promised us that none of our enemies shall enter this city, and, lo! now the Persians attack us." And when the king had said this, holding up the open letter with uplifted hands, suddenly there was a great darkness outside the city before the eyes of the Persians, as they were approaching the city about three miles off; and they were so confounded by the darkness that with difficulty they pitched their camp and surrounded the whole city at the distance of three miles. So confounded were the Persians, that they could never see afterwards in that direction to attack the city; but they guarded the city, shut in as it was all round by foes at the distance of three miles, and thus did they guard it for some months. But after a time, when they saw that in no way could they enter the city, they desired to slay the inhabitants by thirst. Now, at that time, daughter, the little hill which you see above the city supplied the city with water, and the Persians, perceiving this, turned aside the water from the city, and diverted its course by the place where they had pitched their own camp. But on the day and hour on which the Persians diverted the water, the fountains which you see in this place, at the command of God, burst forth all at once, and from that day to this they continue by the grace of God; but the water which the Persians diverted was dried up in that hour, so that the besiegers had nothing to drink, not even for one day, as, indeed, is still apparent, for never after to the present day has any moisture been visible there. And so, at the command of God, who had promised that it should be so, they had forthwith to return to Persia, their own country; for as often as the foe desired to come and take the city by storm, the letter was produced and read in the gate, and straightway they were all driven back by the will of God.' The holy bishop also said: 'The place where these fountains burst forth was formerly a level space inside the city lying under the palace of King Abgar, which palace of Abgar was, as you see it still is, on somewhat higher ground. For it was a custom at that time that palaces should always be built in elevated positions; but after the fountains had burst forth in that place, Abgar built this palace for his son Maanu (that is the one whose statue you saw near his father's), so that the fountains should be enclosed in the palace.' After the holy bishop related all these things, he said to me: 'Let us now go to the gate by which Ananias the courier entered with that letter which I spoke of.'

So when we had come to the gate, the bishop, standing, offered a prayer, and read us the letters, and finally, blessing us, another prayer was offered up. Also the holy man told us, saying: 'From the day that the courier Ananias entered the gate with the letter of the Lord to the present, care is taken that no unclean person nor mourner pass through, neither may a corpse be brought out through this gate.' The holy bishop showed us also the grave of Abgar and of his whole family, very beautiful, but made after the antique manner. He led us also to that higher palace which King Abgar had at the first, and if there were any other places he showed them to us. It also gave me great pleasure to receive from the holy man himself the letters of Abgar to the Lord and of the Lord to Abgar, which the holy bishop read to us there; for although I had copies of them in my own country, yet it seemed to me very pleasing to receive them from him, lest perhaps something less might have reached us at home, for, indeed, the account which I received here is more full.79 So if Jesus our God shall command it, when I come home you also shall read them, ladies, my dear souls.

[Haran.] Having stayed there for three days, it was necessary for me (still advancing) to go on as far as Charræ, as it is now called. In the Holy Scriptures it is called Charran, where holy Abram tarried, as it is written in Genesis, the Lord saying to Abram: 'Get thee out of thy country, and from thy father's house, and go into Charran,' etc.80 When I arrived at Charræ, straightway I went to the church, which is inside the city, and presently I saw the bishop of the place – truly a holy man and a man of God, both monk and confessor – who deigned to show us all the places there which we desired. He conducted us forthwith to the church, which is outside the city, in the place where was the house of holy Abram, i.e., on the same foundations and made of the same stone, as the holy bishop said. So when we had come to this church, prayer was offered, and the passage read from Genesis, one psalm said, and another prayer, and then, the bishop blessing us, we went out. He also deigned to conduct us to that well where holy Rebecca used to draw water, and the holy bishop said to us: 'Behold the well where holy Rebecca gave drink to the camels of holy Abram's servant, Eliezer;'81 and so he deigned to show us each thing. For at the church, which I said is outside the city, ladies, venerable sisters, where at the first Abram's house was, there is now placed the martyr-memorial of a holy monk, by name Elpidius. It happened very pleasantly for us that we arrived there the day before the memorial day of S. Elpidius – i.e., April 23.82 On this day all the monks from all the borders of Mesopotamia had to descend to Charræ, and likewise those elders who live in solitude, whom they call ascetics. On this day also there is a large attendance, on account of the memory of holy Abram, whose house was where the church now is, in which is laid the body of the holy martyr. And so, beyond our expectations, it fell out very pleasantly that we saw there the holy monks of Mesopotamia – truly men of God – and also those whose fame and manner of life were widely spoken of, whom I did not count upon possibly seeing. Not that it was impossible for God, who had vouchsafed to grant me all things, to grant this also, but because I had heard that, except at Easter and on this day, they do not descend from their dwellings (for they are men who perform many acts of virtue), and I did not know in what month the day of the memorial festival was, as I have said; but, at the command of God, it so fell out that I came there on a day which I had not hoped for.

We stayed there two days, on account of the memorial day and to see these holy men, who deigned freely to admit me to salutation and to speak to me, which I did not deserve. After the memorial day they were not seen any more, but presently in the night they sought the desert and each one his own cell where he lived; and in the city, beyond a few clergy and holy monks (if any such delayed there), I saw no Christian, but they were all heathen; 83 for as we observe with great reverence that place where formerly was holy Abram's house, so these heathen with great reverence observe a place about a thousand paces from the city, where are the graves of Nahor and Bethuel. And as the bishop of that place was well instructed in the Scriptures, I asked him, saying: 'I beg of you, sir, to tell me what I desire to hear.' And he said: 'Tell me, daughter, what you wish, and I will tell you if I know it.' Then I said: 'I know from the Scriptures that holy Abram, with Terah his father, and Sarah his wife, and Lot his brother's son, came to this place; but I have not read when Nahor or Bethuel came here, save that I know that afterwards Abram's servant came to Charræ to seek Rebecca, the daughter of Bethuel, the son of Nahor, for Isaac, the son of Abram, his master.' Then the holy bishop said to me: 'Truly, daughter, as you say, it is written in Genesis that holy Abram migrated here with his family, and canonical Scripture84 does not say at what time Nahor or Bethuel migrated with their families; but they manifestly did migrate here afterwards, for their graves are about a thousand paces from the city. But the Scripture testifies that holy Abram's servant came hither to receive holy Rebecca; and again, holy Jacob came here when he received the daughters of Laban the Syrian.'

Then I asked where that well was where holy Jacob had given water to the flocks which Rachel, the daughter of Laban the Syrian, was feeding. And the bishop said to me: 'At the sixth milestone from here there is a place near the village where was the farm of Laban the Syrian; but when you wish to go there we will go with you and show it to you. There are many right holy monks and ascetics, and a holy church is there.' I also asked the holy bishop where was that place of the Chaldees where Terah dwelt at first with his family. Then the holy bishop said to me: 'That place, daughter, which you seek is at the tenth station inland to Persia, for from this to Nisibis there are five stations, and from thence to Hur, which was a city of the Chaldees, there are five more stations; but there is now no access for Romans, as the Persians hold the whole country.85 This district is especially called Eastern which is on the confines of the Romans and the Persians, or the district of the Chaldees.' And many other things he deigned to relate, as also did the other holy bishops and holy monks, all their accounts, however, being either from the Scriptures of God or else of deeds done by holy men – that is, monks – the wonderful things done by those who had departed, or at the present day by those who are yet in the body – those, at least, who are ascetics. For I would not have you think in your pious zeal that the monks ever related any stories except those from the Scriptures of God, or else those of the deeds of the greater monks.

After I had been there two days the bishop conducted us to that well where holy Jacob had watered the flocks of holy Rachel; it is at the sixth milestone from Charræ. In honour of this well is built hard by a holy church, very great and beautiful. When we came to the well prayer was offered by the bishop, the passage from Genesis was read, one psalm appropriate to the place was said, and, after a final prayer, the bishop gave us his blessing. And we saw there lying near the well the enormous stone that Jacob moved from the well, which is shown to this day. Round the well no one lives save the clergy of the church there and the monks who have their cells near, whose truly unheard-of manner of life the holy bishop described to us. Then, prayer having been offered in the church, I made my way with the bishop into the cells of the holy monks, giving thanks to God and to them who deigned to receive me with willing mind into their cells wherever I entered, and to address me with such words as were worthy to come from their lips. And they deigned to give gifts of blessing to me and to all who were with me, as it is the habit of monks to do – at least, to those whom they voluntarily entertain in their cells. [Padan-Aram.] And as the place is in a great plain, I was shown opposite by the holy bishop a very large village, perhaps five hundred paces from the well, through which village we directed our course. This village, as the bishop said, was once the farm of Laban the Syrian; it is called Fadana.86 There I was shown the memorial of Laban the Syrian, Jacob's father-in-law; and I was also shown the place where Rachel stole her father's idols.87 And so, in the name of God, having seen all things, bidding farewell to the holy bishop and the holy monks, who had deigned to conduct us back to that place, we returned by the route and the stations by which we had come from Antioch.

[Antioch.] When I returned to Antioch I stayed there for about a week, until the necessaries for my journey should be prepared. [Tarsus.] And then starting from Antioch, and journeying through several stations, I came to the province called Cilicia, which has Tarsus for its chief city, at which Tarsus I had been already on my way to Jerusalem. But as the martyr-memorial of S. Thecla is at the third station from Tarsus, that is, in Hisauria, it pleased me to go thither, more especially as it was so very near.

Starting from Tarsus, I arrived at a certain city above the sea, but still in Cilicia, called Pompeiopolis. Thence I entered the borders of Hisauria, and halted in a city called Coricus. [Seleucia.] On the third day I arrived at the city called Seleucia in Hisauria. When I arrived there I was at the bishop's, a right holy man, formerly a monk. In the same city I saw a very beautiful church. And since the distance was about 1,500 paces from thence to S. Thecla (which place is outside the city on an elevated tableland), I preferred to go out to it and there make the halt which I purposed. In addition to the holy church nothing else is there save innumerable monasteries, both for men and women. I found there one woman, a very dear friend of mine, to whose life all in the East bore testimony, a holy deaconess, by name Marthana,88 whom I had known at Jerusalem, whither she had gone up for the sake of prayer; she ruled the monasteries of Renuntiants89 and Virgins. When she saw me what joy for both of us! How can I describe it?

But to return. There are very many monasteries on the hill, and in the midst a great wall enclosing the church in which is the martyr-memorial, a very fine thing. And, further, the wall was built to guard the church on account of the Hisauri, who are very mischievous and constantly engage in brigandage, lest by chance they should make an attempt on the monastery which is there appointed. So when I had come in God's name, having offered prayer at the memorial and all the Acts of S. Thecla having been read, I gave countless thanks to Christ our God, who vouchsafed to satisfy in all things the desires of me, unworthy and undeserving. Having stayed there two days, and having seen all the holy monks and renuntiants, men and women, who were there, and having offered prayer and communicated, I returned to my route at Tarsus. Here I stayed three days, and thence, in God's name, set out on my way. Arriving the same day at a station called Mansocrenæ90 wich is under Mount Taurus, I there stopped.

On the next day going along under Mount Taurus, and making my now familiar way through the several provinces I had passed through on my outward journey, viz., Cappadocia, Galatia, and Bithynia, I arrived at Chalcedon, where I stopped on account of the famous martyr-memorial of S. Eufimia91 already well known to me from a former visit. [Constantinople.] On the next day, crossing the sea, I arrived at Constantinople, giving thanks to Christ our God because He had vouchsafed to bestow such grace upon me unworthy and undeserving; for He vouchsafed to grant me not only the wish to go, but the power to walk over the places I desired, and finally to return to Constantinople. When I had got there I went through the several churches – the Church of the Apostles,92 the martyr-memorials, which are there in great numbers; and did not cease to give thanks to Jesus our God, who had vouchsafed to bestow His mercy upon me. From which place, ladies, my loved ones, whilst I prepare this account for your pious zeal, it is already my purpose to go to Asia – to Ephesus – on account of the martyr-memorial of the holy and blessed Apostle John, for the sake of prayer. But if after this I am still in the body, and am able to visit any more places, I shall either tell it to your pious longing in person (if God vouchsafes to grant this), or in any case, if I determine otherwise, I shall acquaint you with it by letter. Only do you, ladies, my loved ones, deign to remember me whether I am 'in the body or out of the body.'93

[Daily service at Jerusalem.] But that your affection may know what services are now held daily in the holy places, I must give you information, for I know that you would gladly learn.

Every day before cockcrow all the doors of the Anastasis94 are opened, and all the monks and virgins (monazontes and parthenæ, as they call them here) descend, and not only these, but also the laity, both men and women, who desire to have an early vigil. From that hour to daybreak hymns are sung, and psalms and antiphons sung in response. And after each hymn prayer is offered. For two or three priests at a time, and likewise the deacons, have their turns every day along with the monks, to say prayers after each hymn or antiphon. When day begins to break then they begin to sing the matin hymns. Then the bishop arrives with the clergy and forthwith enters the cave, and from within the rails he first says a prayer for all; then he commemorates the names of those whom he wishes, and blesses the catechumens. Then he says another prayer and blesses the faithful; and next, as the bishop comes out from within the rails, they all approach [to kiss] his hands, and blessing them one by one, he departs, and so the dismissal is given with the dawn. At the sixth hour they all go down again to the Anastasis, and psalms and antiphons are sung until the bishop is summoned, when he again descends and does not sit down, but enters immediately within the rails inside the Anastasis, that is, inside tho cave, where he was in the early morning; in like manner, he first offers prayer, then blesses the faithful, and then, as he comes out from the rails, they approach [to kiss] his hands as before. And so is it done at the ninth hour as at the sixth.

At the tenth hour – which they call here λυχΝικόΝ, as we say the service of lights – in like manner the crowd collects at the Anastasis; all the candles and wax-tapers are lit, and a great light is made. But the light is not brought from outside; it is fetched from the inner cave, where a lamp burns night and day, i.e., from inside the rails; the vesper psalms are sung, and the antiphons for a good while. But lo! the bishop is summoned, and he comes down and sits on high; also the priests sit in their places; hymns and antiphons are sung. And when they have been recited according to custom, the bishop gets up and stands before the chancel, i.e., before the cave, and one of the deacons makes a commemoration of individuals,95 as is the custom. And while the deacon recites the names of the individuals, many boys stand responding Kyrie eleison, as we say, Lord, have mercy upon us,96 whose voices are innumerable. And when the deacon has recited all that he has to say, first the bishop says a prayer and prays for all; and then they all pray, the faithful and the catechumens together. And then the deacon calls out for each catechumen to bow his head where he stands; and so the bishop, standing, pronounces a benediction over the catechumens. Again prayer is offered, and again the deacon lifts his voice and warns the faithful, standing, to bow their heads. And then the bishop blesses the faithful, and so the dismissal is given from the Anastasis. And they begin severally to approach [to kiss] the hands of the bishop. Afterwards the bishop is escorted from the Anastasis to the Cross with hymns, and all the people go with him. When they have arrived he first offers a prayer, then he blesses the catechumens; then another prayer is offered, then he blesses the faithful. And after that the bishop and the whole crowd go behind the Cross, and there are there again similar ceremonies to those in front of the Cross. In like manner as at the Anastasis, they approach [to kiss] the bishop's hands; as in front of the Cross, so behind the Cross. Everywhere hang numbers of great bright candles and wax-tapers before the Anastasis, and also in front of and behind the Cross. All these ceremonies are finished in the dark. This service is held every weekday at the Cross and at the Anastasis.