THE BUILDING AND ITS DECORATION.

THE great work of the world is carried on by those inseparable yoke-mates man and woman, but there are certain feminine touches in the spiritual architecture which each generation raises as a temple to its own genius, and it is as a record of this essentially feminine side of human effort that the Woman's Building is dedicated.

In the dread art of war the male element of the race asserts itself alone. In its antithesis, the art of peace, woman is paramount. We are yoke-fellows, equal and indivisible, tugging and straining at the load of humanity which we must drag a few paces onward ere our work is done. On the outskirts of the throng of tireless workers there are a few men and women who, when the heat and stress of the day are over, climb to the hill-tops, and looking into the mute heavens read the promise of the coming day. A generation ago the seers of our race foretold two great things: a material growth and prosperity, the like of which the world has never seen; a mastery of electricity, that most potent of man's friendly genii, and a great city through which the traffic of the world should roll, one of the strongholds of the earth—all this the voice of the male seer foretold from his tower, and much more.

A clearer, sweeter prophecy went forth from the tower where the wise women watched the signs of the times: "Woman the acknowledged equal of man; his true helpmate, honored and beloved, honoring and loving as never before since Adam cried, 'The woman tempted me and I did eat.'"

We have eaten of the fruit of the tree of knowledge and the Eden of idleness is hateful to us. We claim our inheritance and are become workers, not cumberers of the earth.

Twenty years ago to be called strong-minded was a reproach which brought the blood to the cheek of many a woman. To-day there are few of our sisters who do not prefer to be classed among strong-minded rather than among weak-minded women. The battle has been fought out, and the veterans who have been wounded and scarred with that cruelest weapon of ridicule, smile

DECORATION OF NORTH TYMPANUM—"PRIMITIVE WOMAN." MARY FAIRCHILD MACMONNIES. UNITED STATES.

to see how easily we assume the position which they gave the glory of their youth to win for us. We honor these women and have written their names in golden letters for all the world to see and salute in our Hall of Honor.

To see the work of woman at the World's Fair we must go through every department of human ingenuity, for there is scarcely one of these where woman's hand has not done a share of the work. The work of man and woman, like their interests, is one and indivisible.

In welcoming the visitor to our building, we would say: "Enter here for a space; sit in our library and rest your eyes with its soft colors; pace through our Hall of Honor and understand the spirit in which it is raised; leave criticism upon the threshold as you enter. Our salutation is, 'Peace be with you.' May your answer be, 'And with you be peace.'"

When I first wandered through the courts of this miraculous city, which has arisen as if by magic out of the desolate borderland between the prairie and the lake, I was moved, as rarely ever before, by the work of man's hand. I have stood upon the edge of the Egyptian desert and gazed with questioning eyes upon the mighty sphinx. I have seen the glories of the Acropolis and knelt at the shrine of the Greek, but neither of these superlative legacies of the past impressed me more than did this prophecy of the future. For the first time in the history of our nation, the spirit of art has asserted itself, and

DECORATION OF SOUTH TYMPANUM — "MODERN WOMAN." MARY CASSATT. UNITED STATES.

triumphs over its handmaidens, commerce and manufacture. The beauties of the Athens of Pericles, the Rome of Augustus, are indeed recalled by what we see, but a new art is foretold, whose ruins will one day be honored as we honor the classic fragments of Greece and Rome to-day. Comparison is nowhere more odious than where all is excellent; in my own thought our building stands on its own merits, and yet it bears comparison with all the rest, and loses nothing by it. There may be others which have qualities which it lacks. It borrows beauty from its August neighbors and from its mirrored reflection in the lagoon, but it lends as much as it receives, and the winged temple is joyfully restful to eyes wearied with much gazing. A work of art is precious in so far as it expresses the personality of its creator. Architecture is one of the arts most subservient to use, and a building should not only express the genius of the architect but the purpose to which it is dedicated. How well the architects of the great Gothic churches understood this law. No other form of religious architecture expresses so exalted a spirituality as theirs. The aspiring lines, the upspringing arches of the great Gothic cathedrals lead the eyes upward to the sky; the mind to reflection and aspiration. Our building is essentially feminine in character; it has the qualities of reserve, delicacy, and refinement. Its strength is veiled in grace; its beauty is gently impressive; it does not take away the breath

DECORATIVE PANEL—"THE WOMEN OF PLYMOUTH."

LUCIA FAIRCHILD.

UNITED STATES.

with a sudden passion of admiration, like some of its neighbors, but it grows upon us day after day, like a beloved face whose beauty, often forgotten because the face is loved for itself, now and again breaks upon us with all the charm of novelty. I came upon our building suddenly one early morning, when the mist-curtain was rolling away under a crisp breeze and an ardent sun. My heart leaped to a more generous measure. I drew my breath

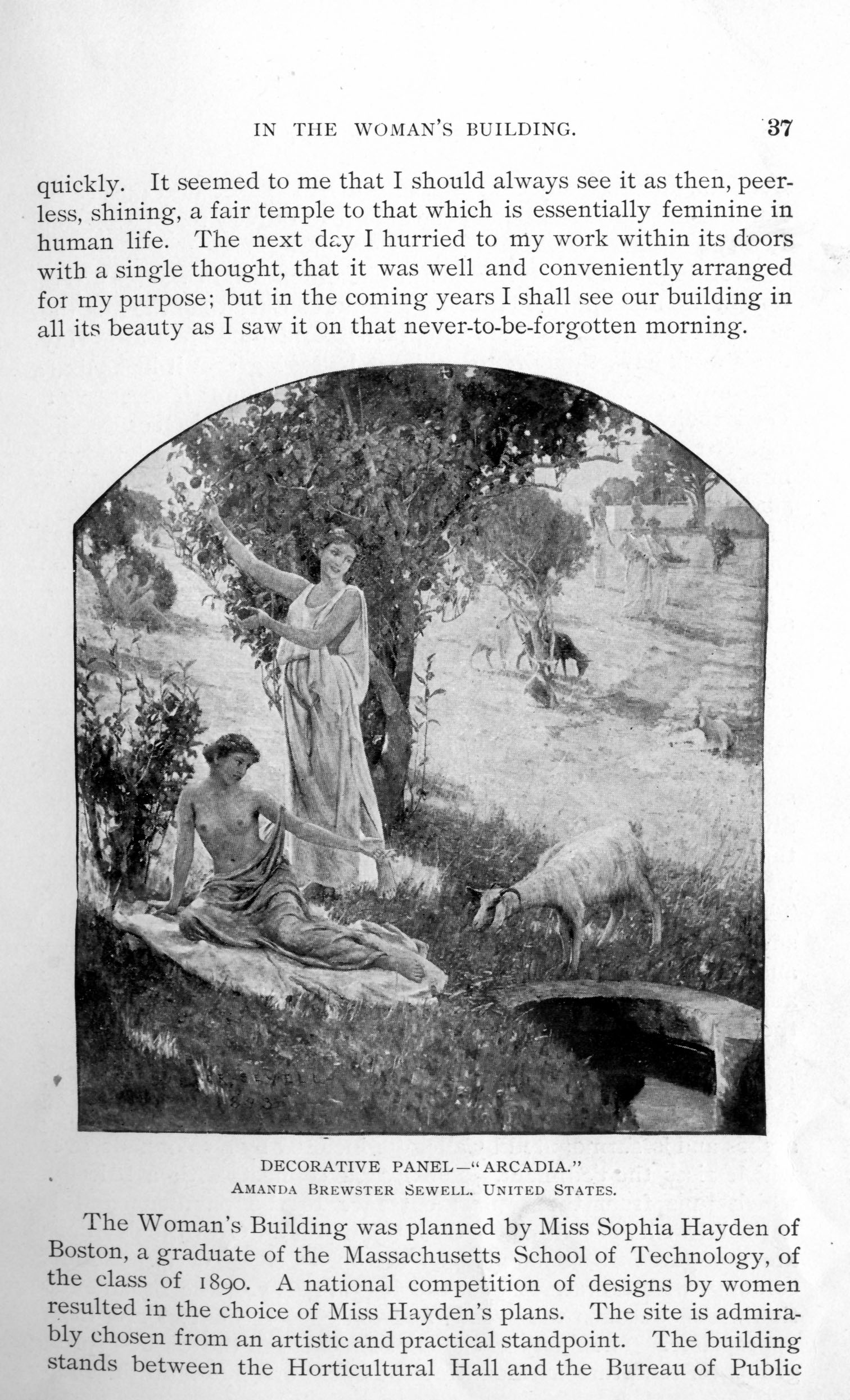

DECORATIVE PANEL—"ARCADIA." AMANDA BREWSTER SEWELL. UNITED STATES.

quickly. It seemed to me that I should always see it as then, peerless, shining, a fair temple to that which is essentially feminine in human life. The next day I hurried to my work within its doors with a single thought, that it was well and conveniently arranged for my purpose; but in the coming years I shall see our building in all its beauty as I saw it on that never-to-be-forgotten morning.

The Woman's Building was planned by Miss Sophia Hayden of Boston, a graduate of the Massachusetts School of Technology, of the class of 1890. A national competition of designs by women resulted in the choice of Miss Hayden's plans. The site is admirably chosen from an artistic and practical standpoint. The building stands between the Horticultural Hall and the Bureau of Public

Comfort, directly adjacent to the Sixtieth Street entrance of the Fair. The nearest station of the suburban railway may be reached in a two minutes' walk.

Nothing is more significant of the difference in woman's position in the first and the latter half of our century than the fact that none of the eminent writers who have commented upon Miss Hayden's work have thought to praise it by saying that it looks like a man's work. Marian Evans and Aurore Dupin found it necessary to cloak their womanhood under the noms de plume of George Eliot and George Sand. Rosa Bonheur found it convenient to wear man's attire while visiting the Parisian stock-yards in order to study the animals for her great pictures. At that time the highest praise that could be given to any woman's work was the criticism that it was so good that it might be easily mistaken for a man's. To-day we recognize that the more womanly a woman's work is the stronger it is. In Mr. Henry Van Brunt's appreciative account of Miss Hayden's work, the writer points out that it is essentially feminine in quality, as it should be. If sweetness and light were ever expressed in architecture, we find them in Miss Hayden's building. Every line expresses elegance, grace, harmony.

The building is in the style of the villas of the Italian Renaissance. It is 388 feet long, 199 feet wide, and 70 feet high. It is divided into two stories, which are clearly indicated by the lines of the exterior. The most important feature required of the architect was the Hall of Honor, which forms the middle of the structure. This is a noble apartment, rising to the full height of the building, surrounded by a lower two-story structure forming the four facades, and containing the minor halls and offices required for committee and exhibition rooms. At the second story a corridor surrounds the hall, treated in the way of a cloister, with graceful arches springing from well-proportioned columns. Looking at the building from the water side, we have a central entrance and a pavilion at each end connected by an arcade. The main entrance has three arches and is surmounted by a loggia inclosed by a colonnade, over which rises the pediment. The loggia connects with a balcony, which runs from the central entrance to the pavilions and is enriched with pilasters of the Corinthian order. Over the pavilions are roof-gardens, surrounded by an open screen of light Ionic columns, with caryatides over the loggia below. The ornamentation which outlines the arches and enriches the exterior is most appropriate. The finely modeled pediment and the eight typical groups of sculpture surmounting the open screen around the roof-

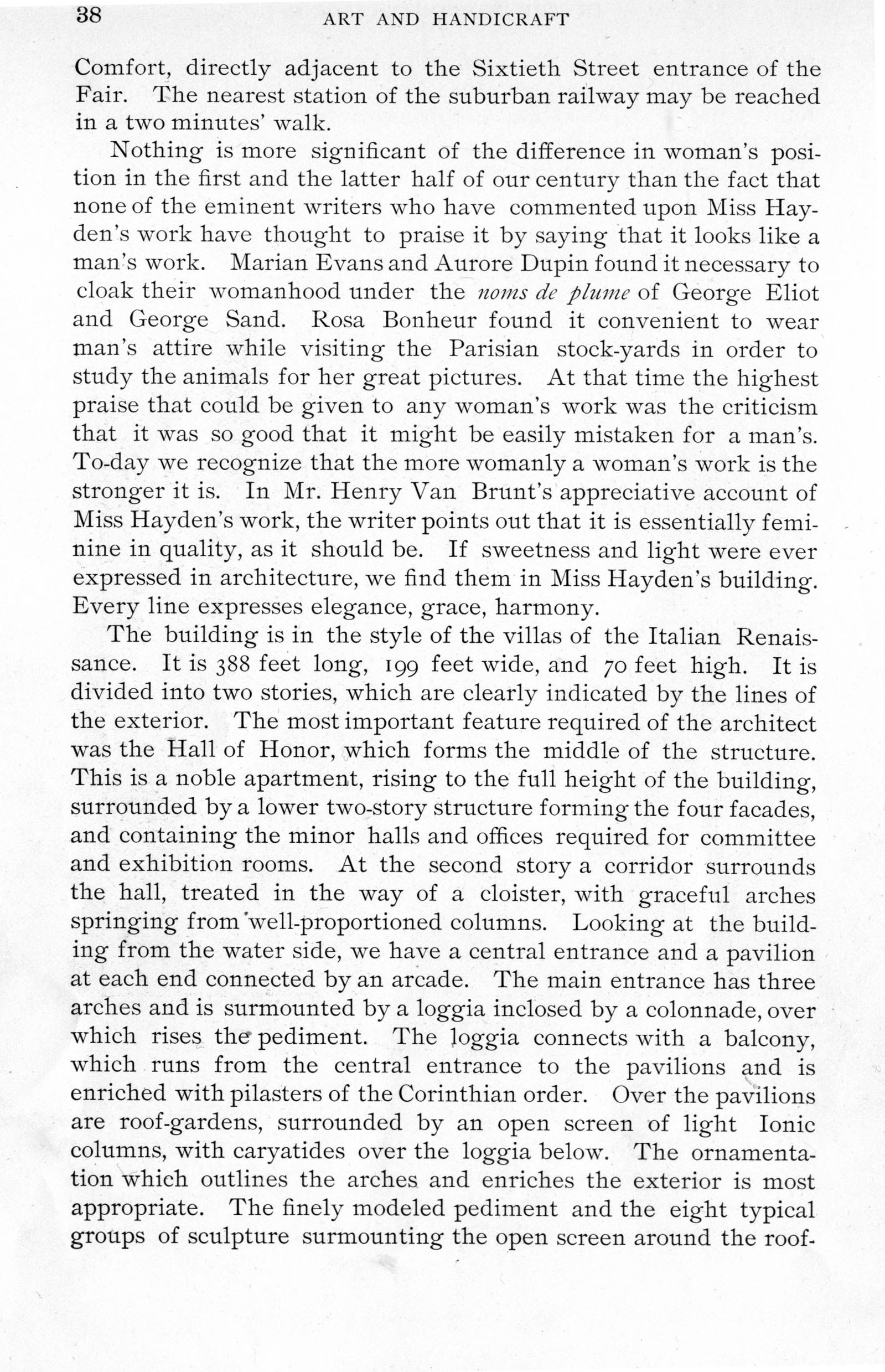

DECORATIVE PANEL—"THE REPUBLIC'S WELCOME TO HER DAUGHTERS."

ROSINA EMMET SHERWOOD. UNITED STATES. (Copyrighted.)

garden are in harmony with the purity, simplicity, and dignity of the building, proving that Miss Rideout, the young Californian sculptor of these charming groups, worked in perfect sympathy with the architect.

The group represented in the pediment typifies woman's work in the various walks of life. The central figure is full of spirit and charm. In one hand she holds a myrtle wreath; in the other, the scales of justice. On her right, we find Woman the Benefactor; and on her left, the Woman, the Artist and Littérateur. The figures are modeled in very high relief, and the whole work has an

infinitely joyous and hopeful quality. This is equally true of the winged groups, which are in delightful contrast to the familiar and hackneyed types that serve to represent Virtue, Sacrifice, Charity, and the other qualities which sculptors have personified, time out of mind, by large, heavy, dull-looking stone women. The sculpture throughout the Fair is of a character that deserves a more lasting form than it now possesses. A large proportion of the plaster figures of men, women, and animals which enrich the White City deserve to be preserved in bronze or marble infinitely more than most of the sculpture which is shown in the art gallery.

Hereafter the old charge that there is no art atmosphere in our country will, I think, prove a futile and groundless one. A single visit to the World's Fair must convince the most indifferent European-American that, whatever may have been the case at an earlier period, the country which has produced this great, harmonious, artistic whole is not entirely lacking in art atmosphere.

One of the pleasantest features of this building is the hospitality suggested throughout; the cool and quiet arcades where the visitor may sit and look out upon the varied scenes hourly enacted in that corner of the World's Fair; the roof-gardens, from which a fine view may be had of the distant buildings, with the shimmering lake beyond. Here one may dine comfortably and well, or enjoy "a dish of tea and talk," at the end of the long day of work and pleasure. Our building's highest mission perhaps will be to soothe, to rest, to refresh the great army of sight-seers who march daily through the Fair.

I have heard from these birds of passage various interesting comments on our building. One of these I remember as particularly expressive of its influence, coming as it did from a tired woman, who had labored generously and ceaselessly for many months at her little part of the great work. "I call it the flying building," she said; "it seems to lift the weight off my feet when I look at those big angels."

The interior decoration is as appropriate and simple as the exterior. Touches of gold, here and there, relieve the purity of the whitest building in all the White City. The Hall of Honor is unbroken by pillars or supports, and rises grandly to its seventy feet of height. It is 67 ½ feet wide and 200 feet long. Statistics, however, avail us but little in looking at this noble hall, and it is best to remember only that it is as high as our hopes for it have been. Honored names are here written in letters of gold—the names of women great in art, in song, in thought, in science, in statecraft, and in liter-

Engraved by Rand, McNally & Co.

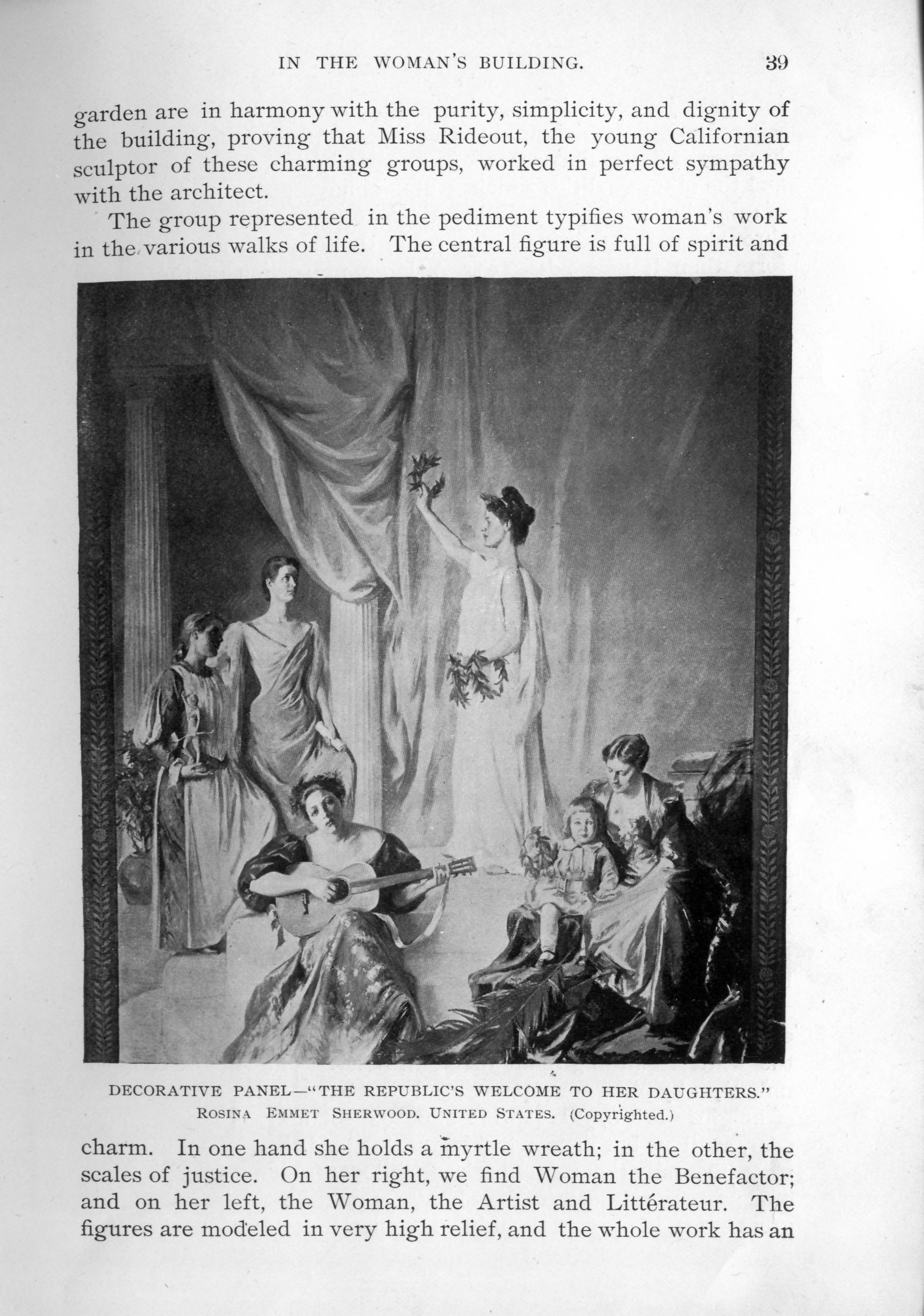

THE COLUMBIAN FOUNTAIN.

DESIGNED BY FREDERICK MACMONNIES.

COLUMBIA, ENTHRONED, IS PROPELLED BY THE ARTS AND SCIENCES AND STEERED BY FATHER TIME.

Engraved by Rand, McNally & Co.

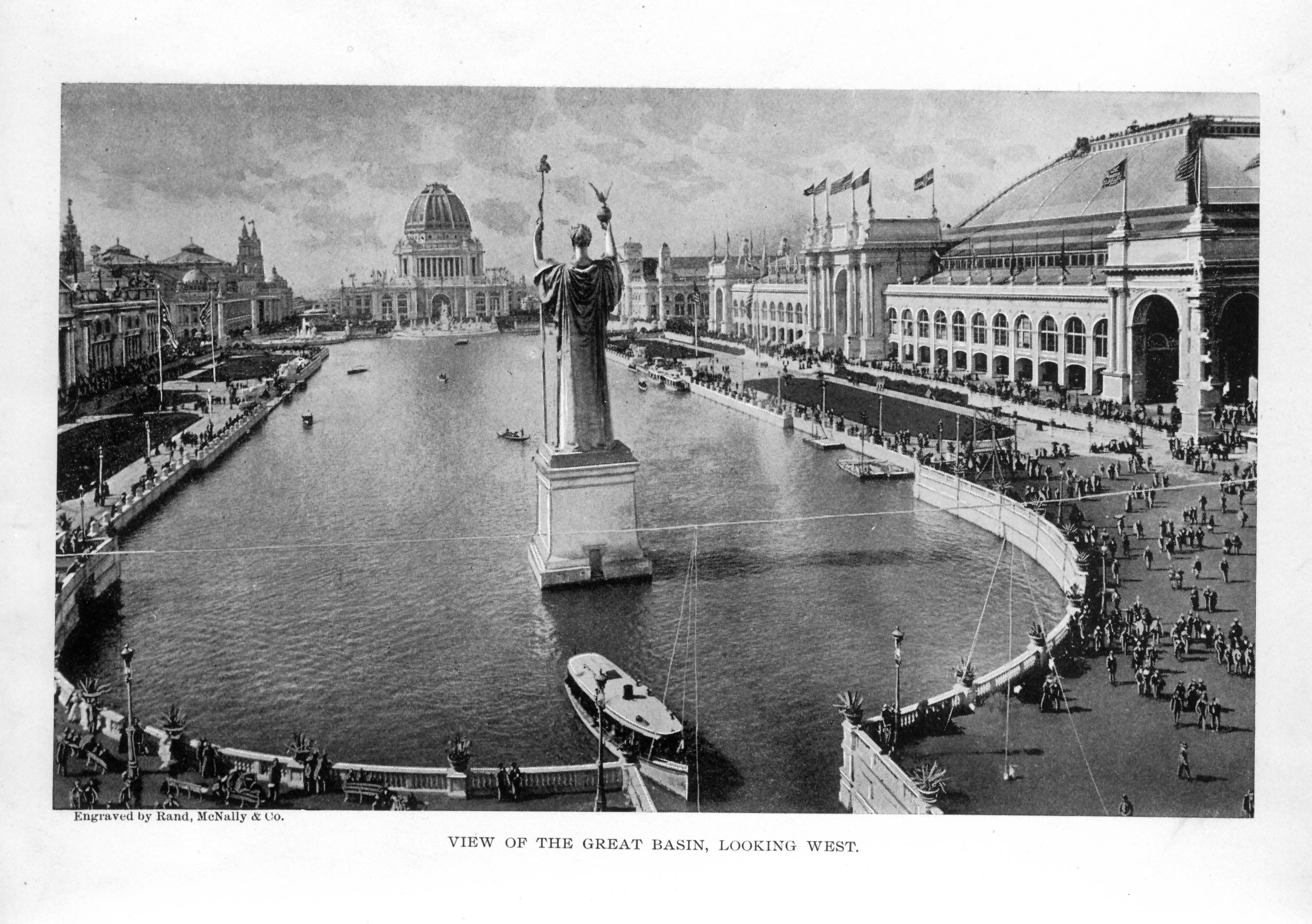

VIEW OF THE GREAT BASIN, LOOKING WEST.

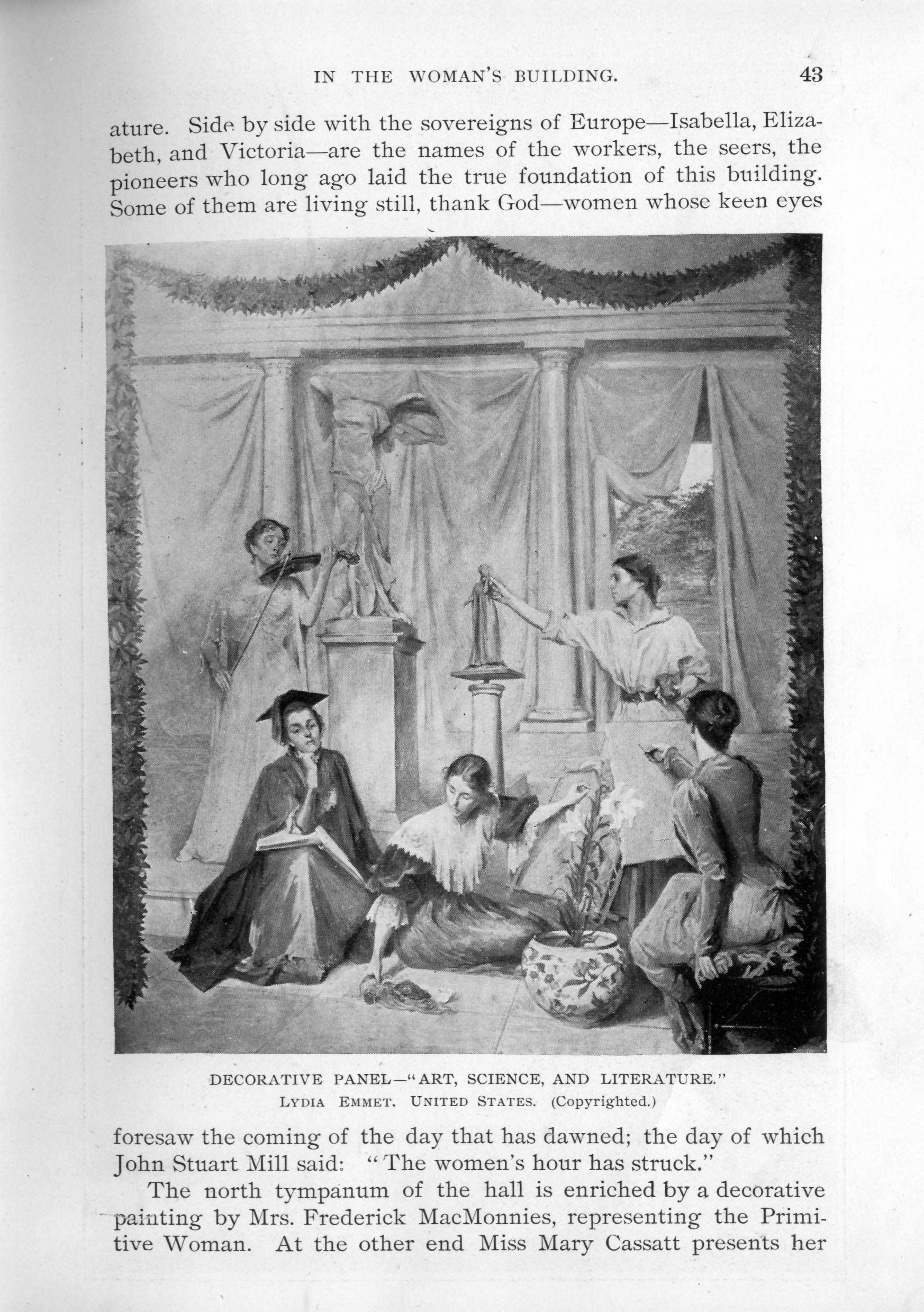

DECORATIVE PANEL—"ART, SCIENCE, AND LITERATURE."

LYDIA EMMET. UNITED STATES. (Copyrighted.)

ature. Side by side with the sovereigns of Europe—Isabella, Elizabeth, and Victoria—are the names of the workers, the seers, the pioneers who long ago laid the true foundation of this building. Some of them are living still, thank God—women whose keen eyes foresaw the coming of the day that has dawned; the day of which John Stuart Mill said: "The women's hour has struck."

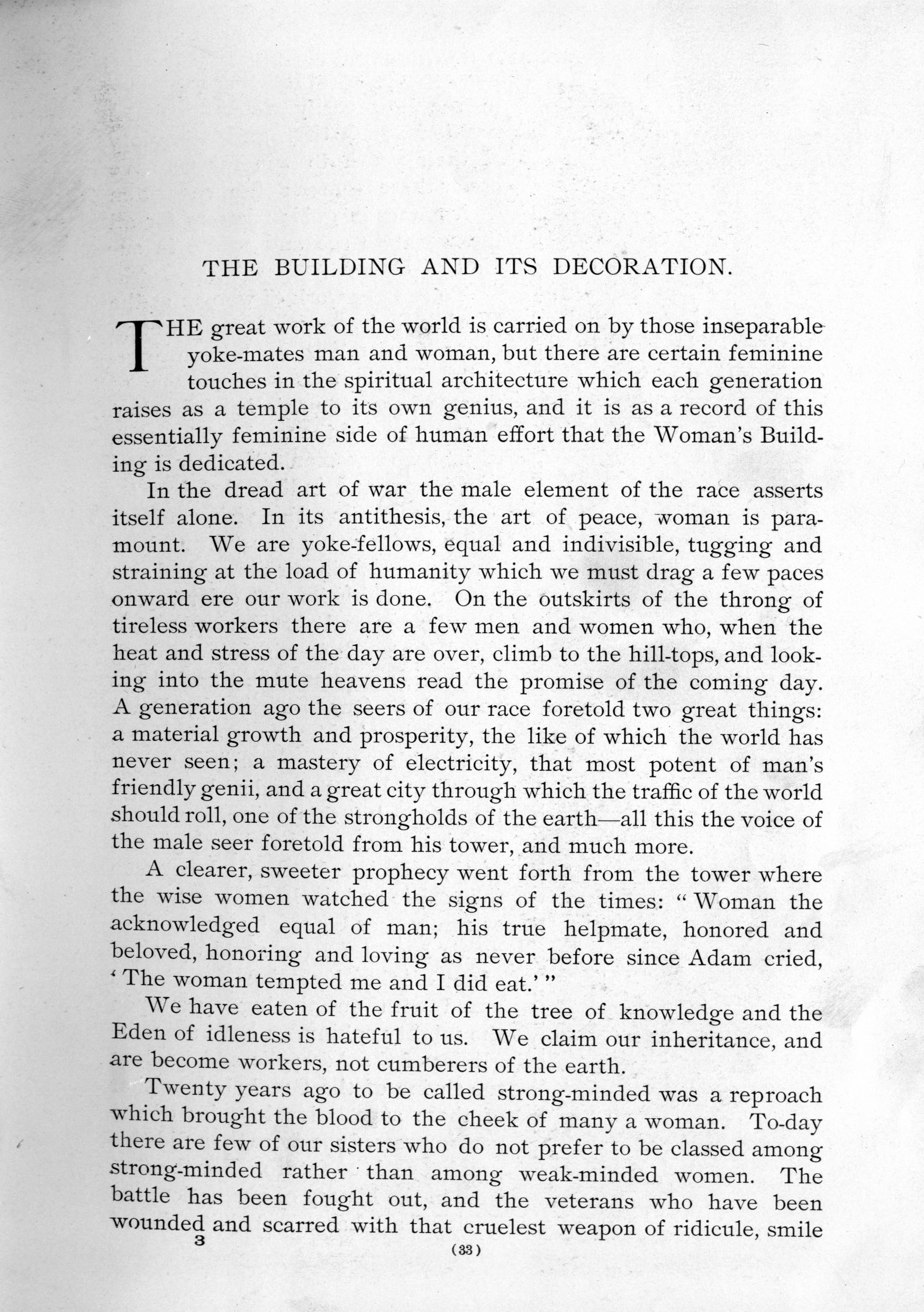

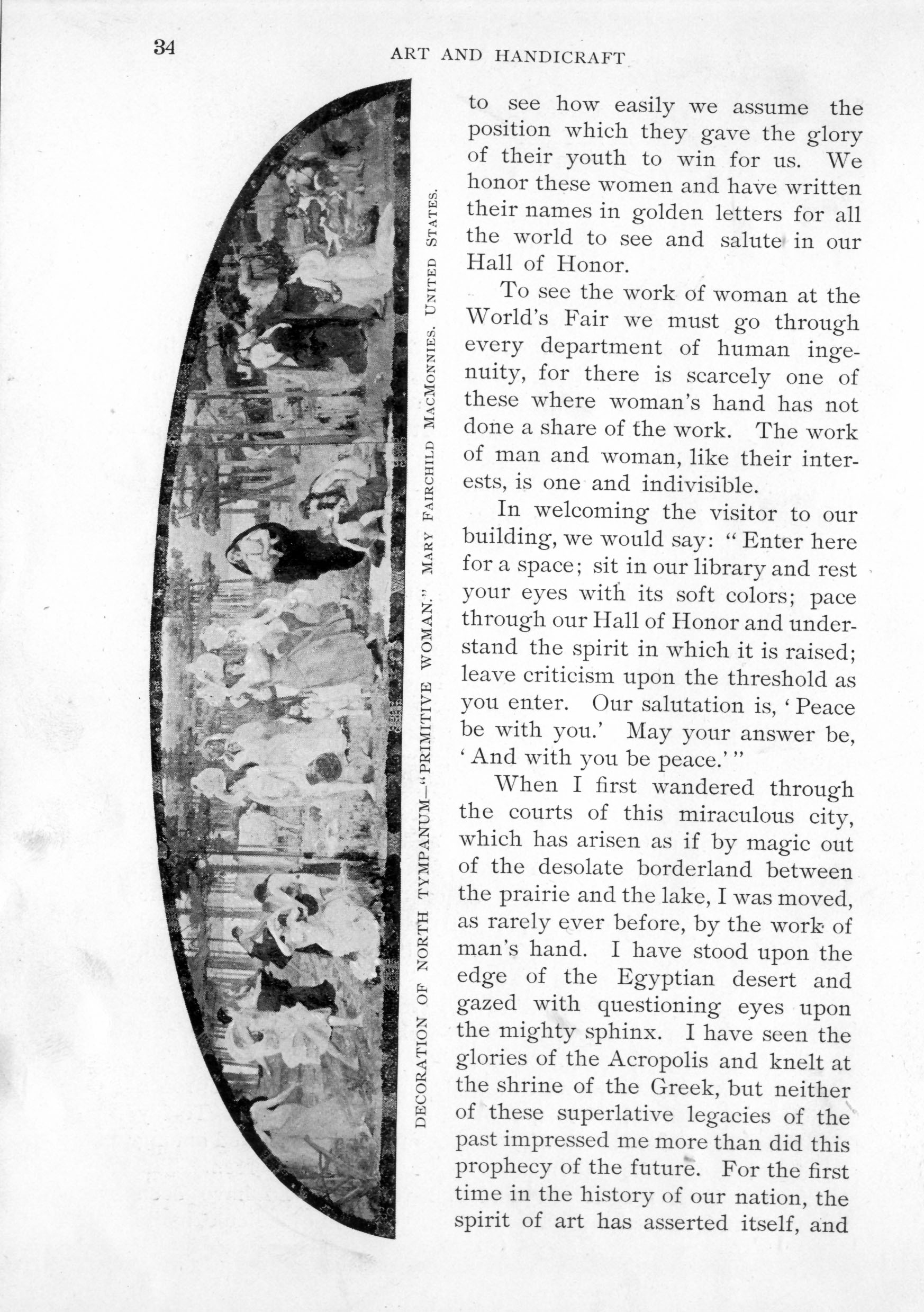

The north tympanum of the hall is enriched by a decorative painting by Mrs. Frederick MacMonnies, representing the Primitive Woman. At the other end Miss Mary Cassatt presents her

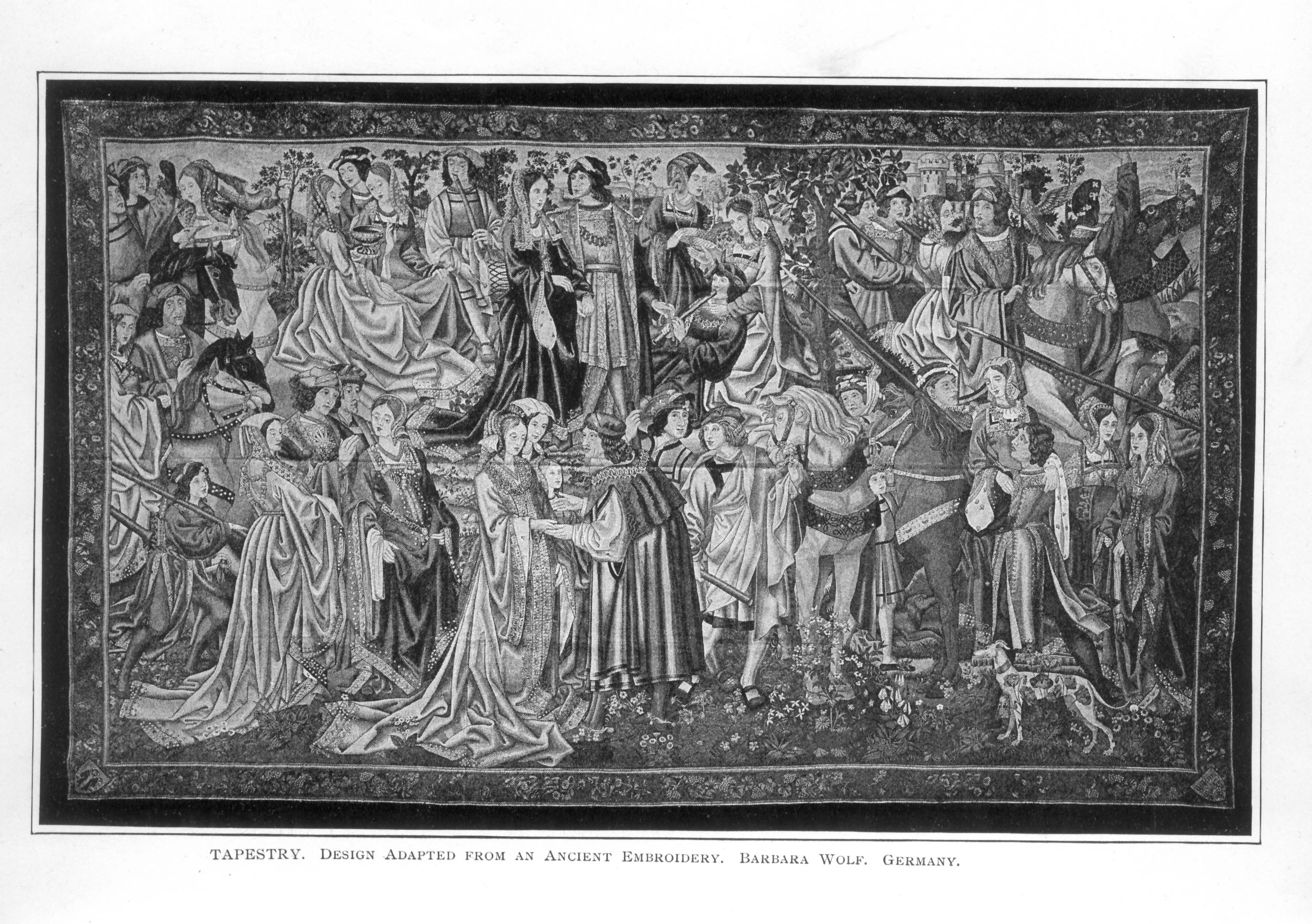

TAPESTRY.

DESIGN ADAPTED FROM AN ANCIENT EMBROIDERY. BARBARA WOLF. GERMANY.

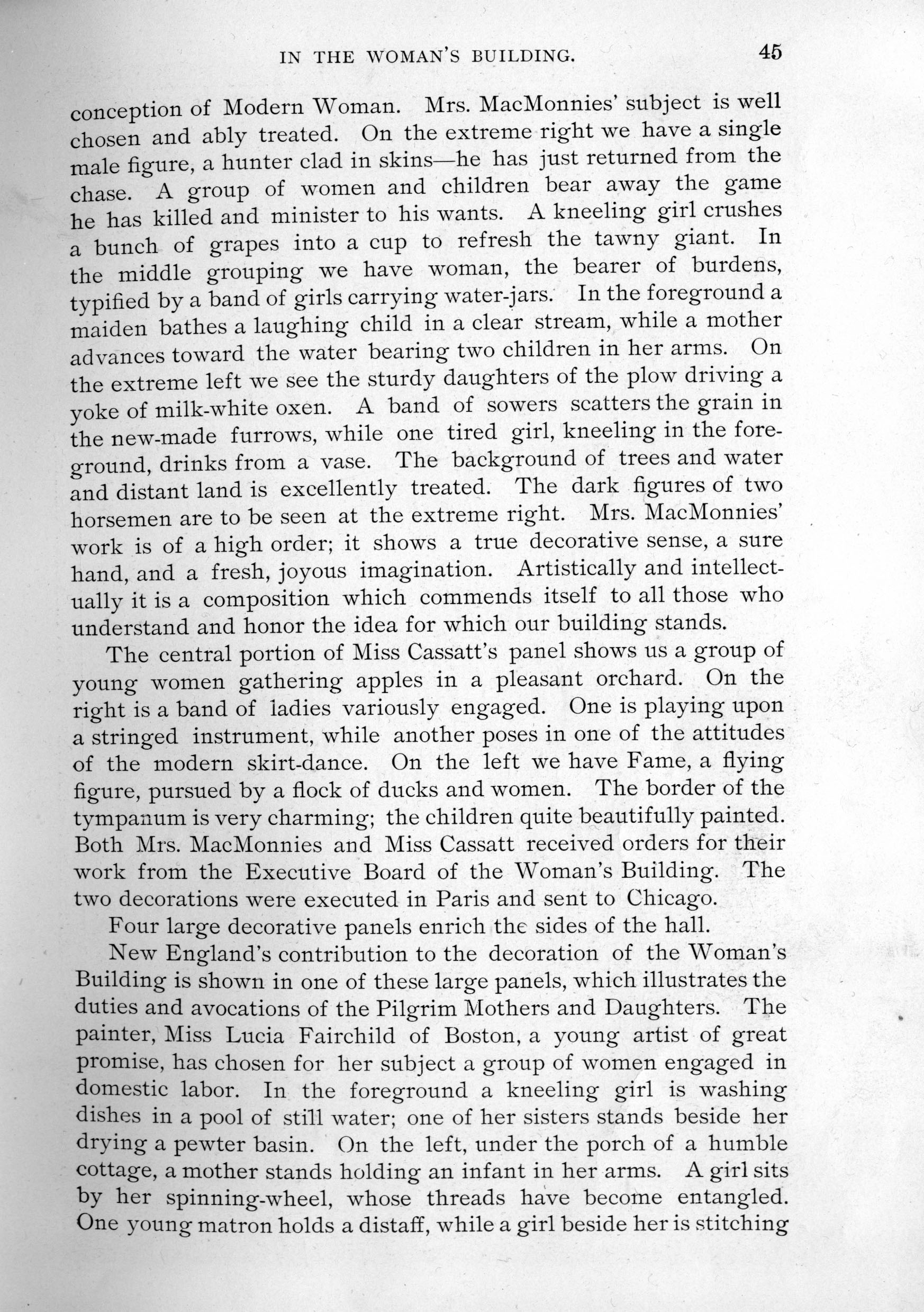

conception of Modern Woman. Mrs. MacMonnies' subject is well chosen and ably treated. On the extreme right we have a single male figure, a hunter clad in skins—he has just returned from the chase. A group of women and children bear away the game he has killed and minister to his wants. A kneeling girl crushes a bunch of grapes into a cup to refresh the tawny giant. In the middle grouping we have woman, the bearer of burdens, typified by a band of girls carrying water-jars. In the foreground a maiden bathes a laughing child in a clear stream, while a mother advances toward the water bearing two children in her arms. On the extreme left we see the sturdy daughters of the plow driving a yoke of milk-white oxen. A band of sowers scatters the grain in the new-made furrows, while one tired girl, kneeling in the foreground, drinks from a vase. The background of trees and water and distant land is excellently treated. The dark figures of two horsemen are to be seen at the extreme right. Mrs. MacMonnies' work is of a high order; it shows a true decorative sense, a sure hand, and a fresh, joyous imagination. Artistically and intellectually it is a composition which commends itself to all those who understand and honor the idea for which our building stands.

The central portion of Miss Cassatt's panel shows us a group of young women gathering apples in a pleasant orchard. On the right is a band of ladies variously engaged. One is playing upon a stringed instrument, while another poses in one of the attitudes of the modern skirt-dance. On the left we have Fame, a flying figure, pursued by a flock of ducks and women. The border of the tympanum is very charming; the children quite beautifully painted. Both Mrs. MacMonnies and Miss Cassatt received orders for their work from the Executive Board of the Woman's Building. The two decorations were executed in Paris and sent to Chicago.

Four large decorative panels enrich the sides of the hall.

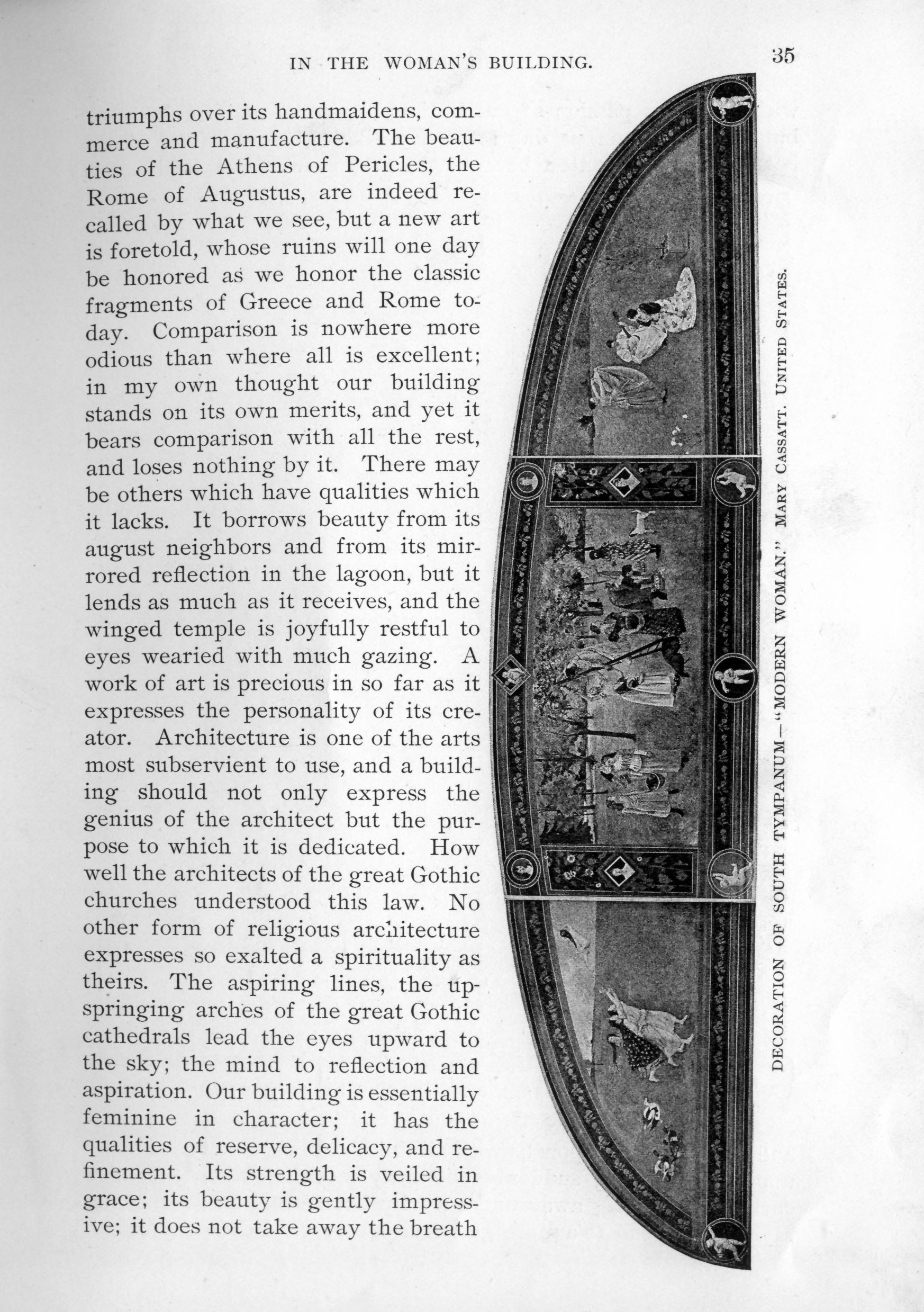

New England's contribution to the decoration of the Woman's Building is shown in one of these large panels, which illustrates the duties and avocations of the Pilgrim Mothers and Daughters. The painter, Miss Lucia Fairchild of Boston, a young artist of great promise, has chosen for her subject a group of women engaged in domestic labor. In the foreground a kneeling girl is washing dishes in a pool of still water; one of her sisters stands beside her drying a pewter basin. On the left, under the porch of a humble cottage, a mother stands holding an infant in her arms. A girl sits by her spinning-wheel, whose threads have become entangled. One young matron holds a distaff, while a girl beside her is stitching

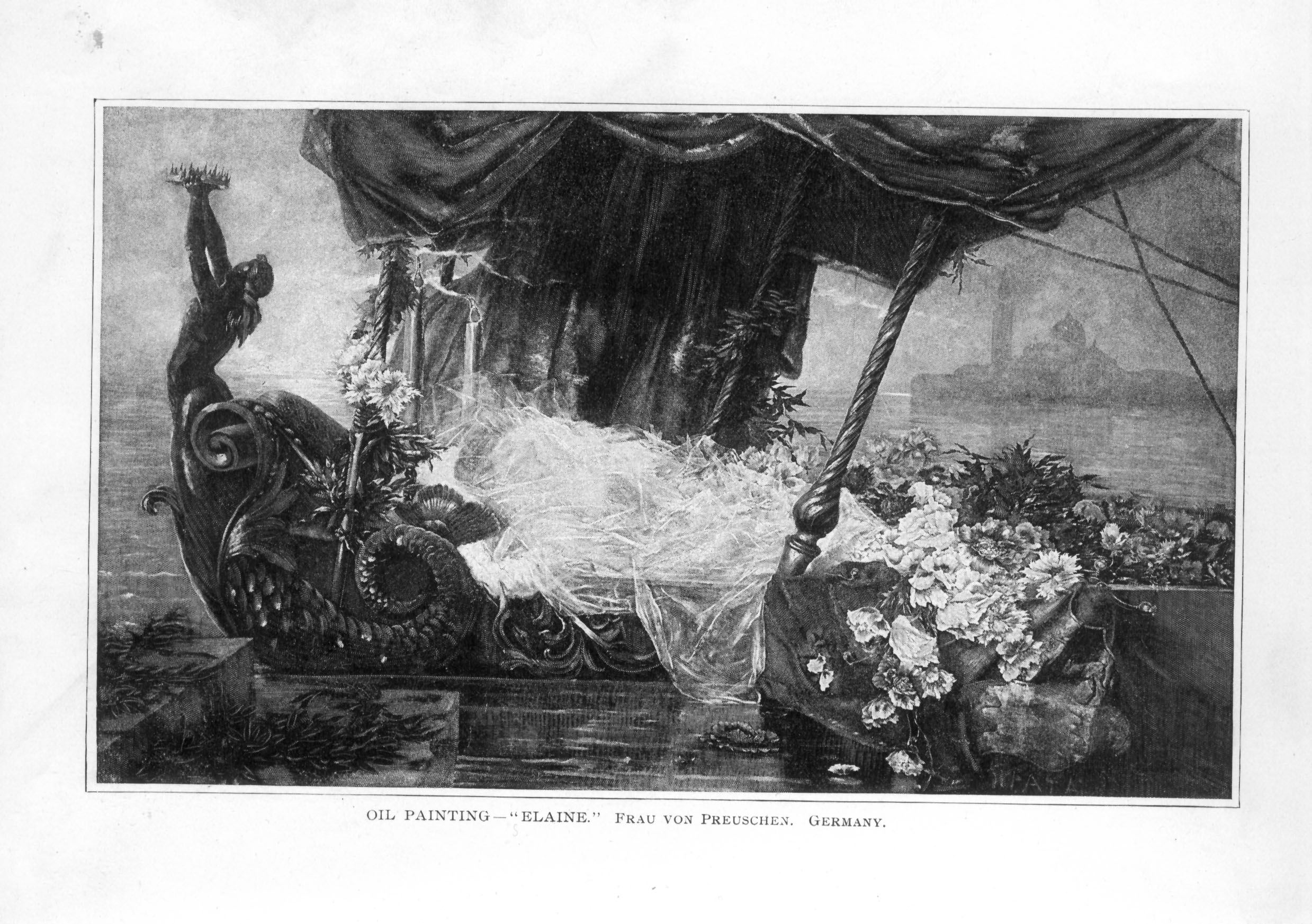

OIL PAINTING — "ELAINE."

FRAU VON PREUSCHEN. GERMANY.

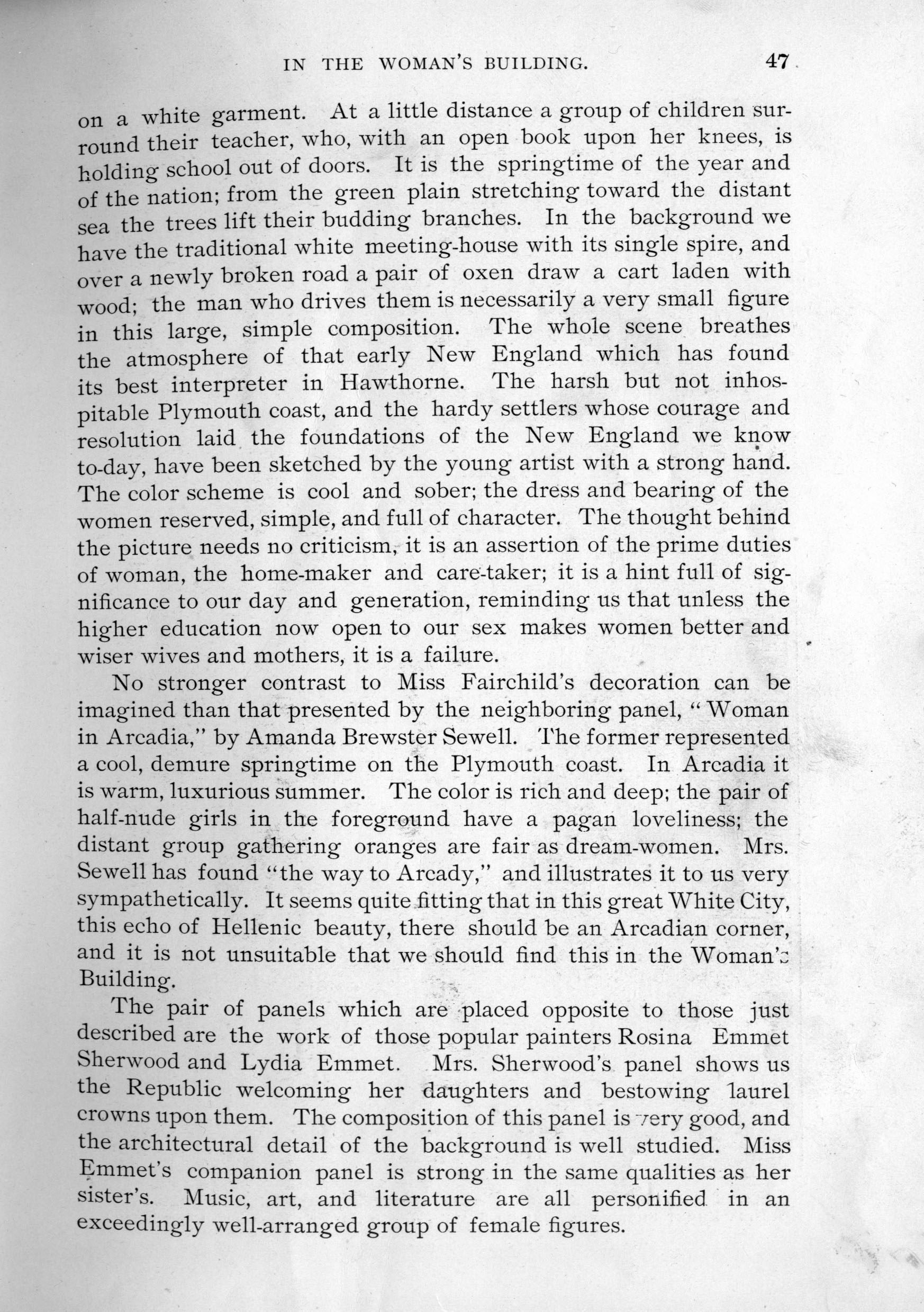

on a white garment. At a little distance a group of children surround their teacher, who, with an open book upon her knees, is holding school out of doors. It is the springtime of the year and of the nation; from the green plain stretching toward the distant sea the trees lift their budding branches. In the background we have the traditional white meeting-house with its single spire, and over a newly broken road a pair of oxen draw a cart laden with wood; the man who drives them is necessarily a very small figure in this large, simple composition. The whole scene breathes the atmosphere of that early New England which has found its best interpreter in Hawthorne. The harsh but not inhospitable Plymouth coast, and the hardy settlers whose courage and resolution laid the foundations of the New England we know to-day, have been sketched by the young artist with a strong hand. The color scheme is cool and sober; the dress and bearing of the women reserved, simple, and full of character. The thought behind the picture needs no criticism, it is an assertion of the prime duties of woman, the home-maker and care-taker; it is a hint full of significance to our day and generation, reminding us that unless the higher education now open to our sex makes women better and wiser wives and mothers, it is a failure.

No stronger contrast to Miss Fairchild's decoration can be imagined than that presented by the neighboring panel, "Woman in Arcadia," by Amanda Brewster Sewell. The former represented a cool, demure springtime on the Plymouth coast. In Arcadia it is warm, luxurious summer. The color is rich and deep; the pair of half-nude girls in the foreground have a pagan loveliness; the distant group gathering oranges are fair as dream-women. Mrs. Sewell has found "the way to Arcady," and illustrates it to us very sympathetically. It seems quite fitting that in this great White City, this echo of Hellenic beauty, there should be an Arcadian corner, and it is not unsuitable that we should find this in the Woman's Building.

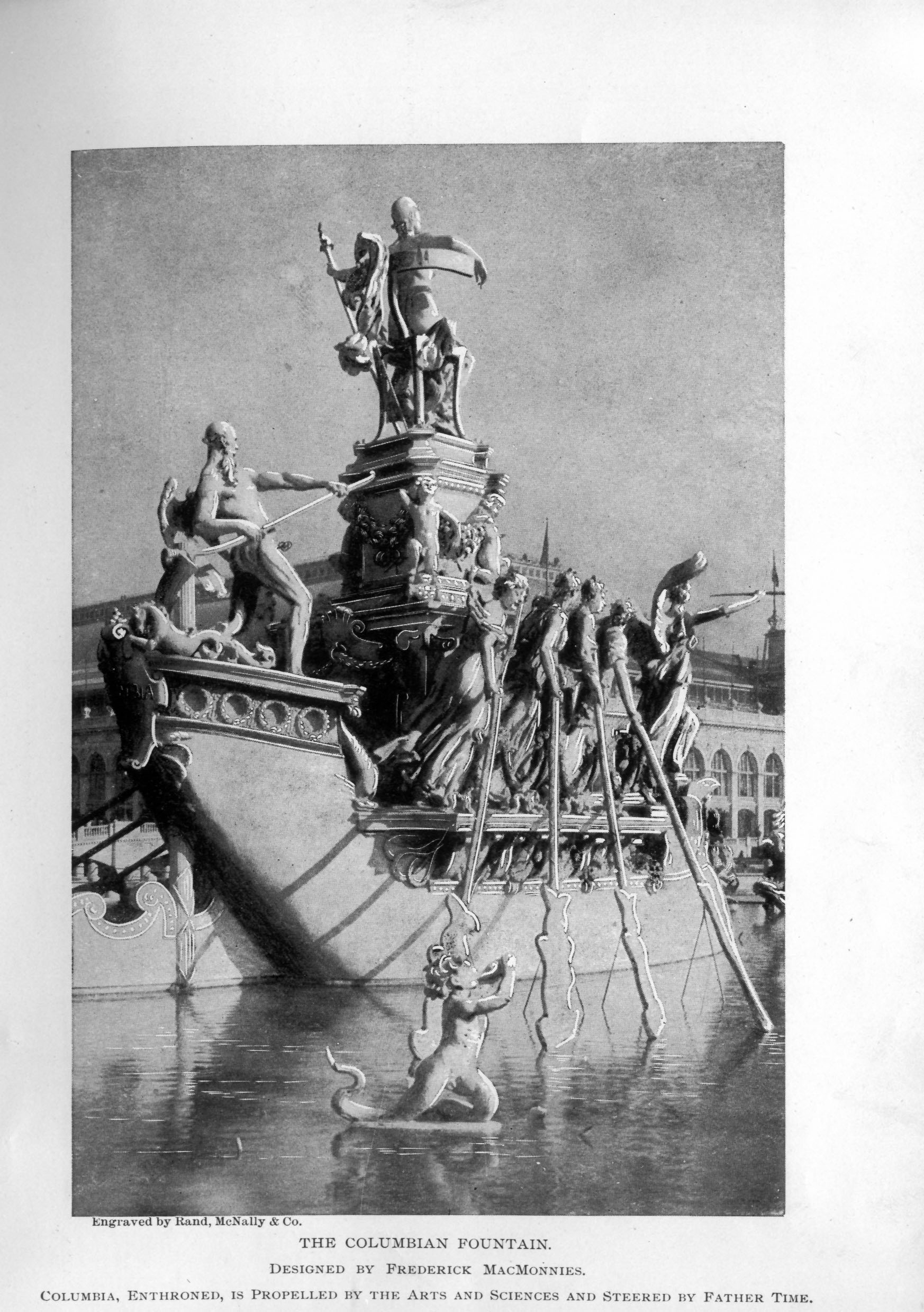

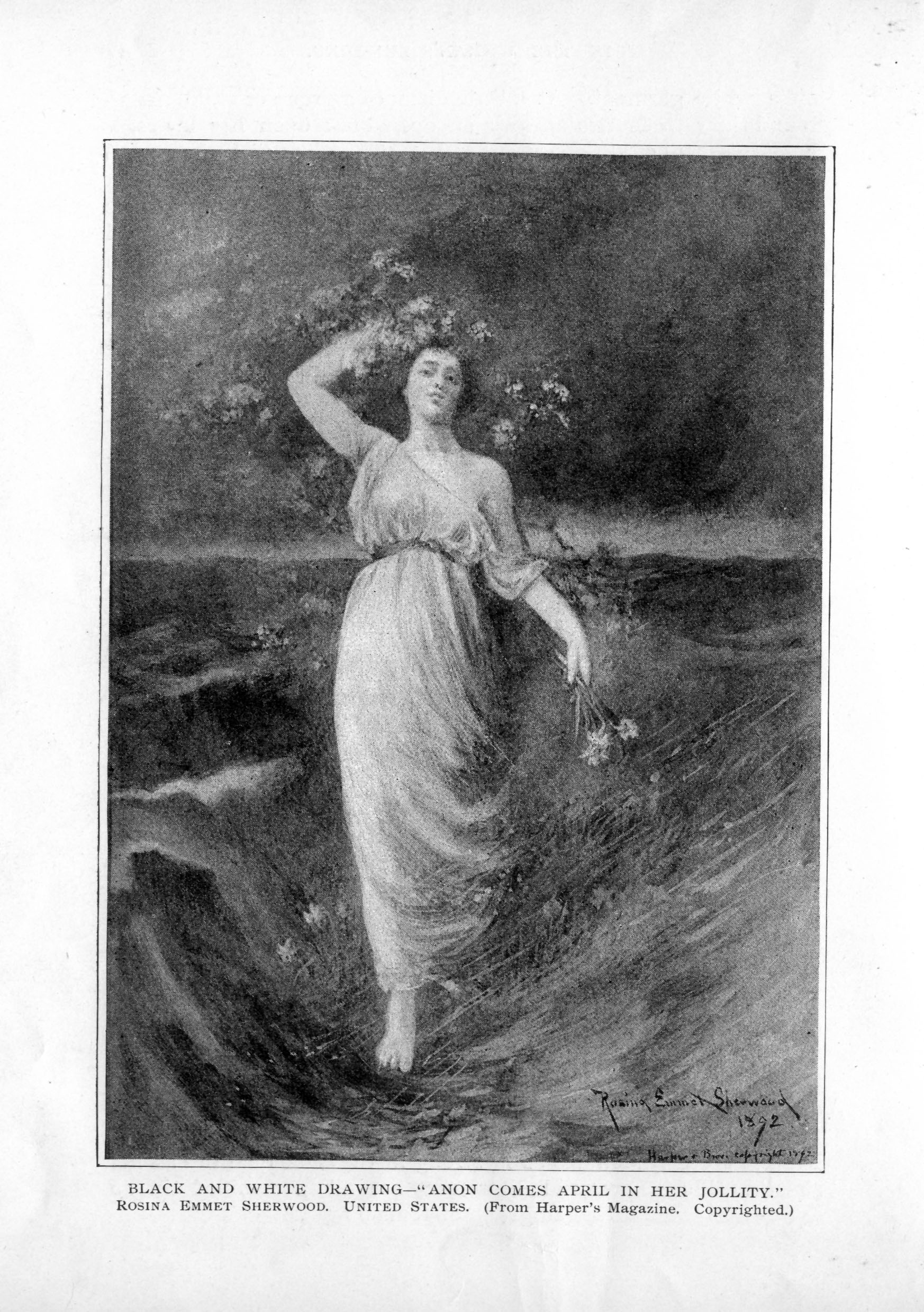

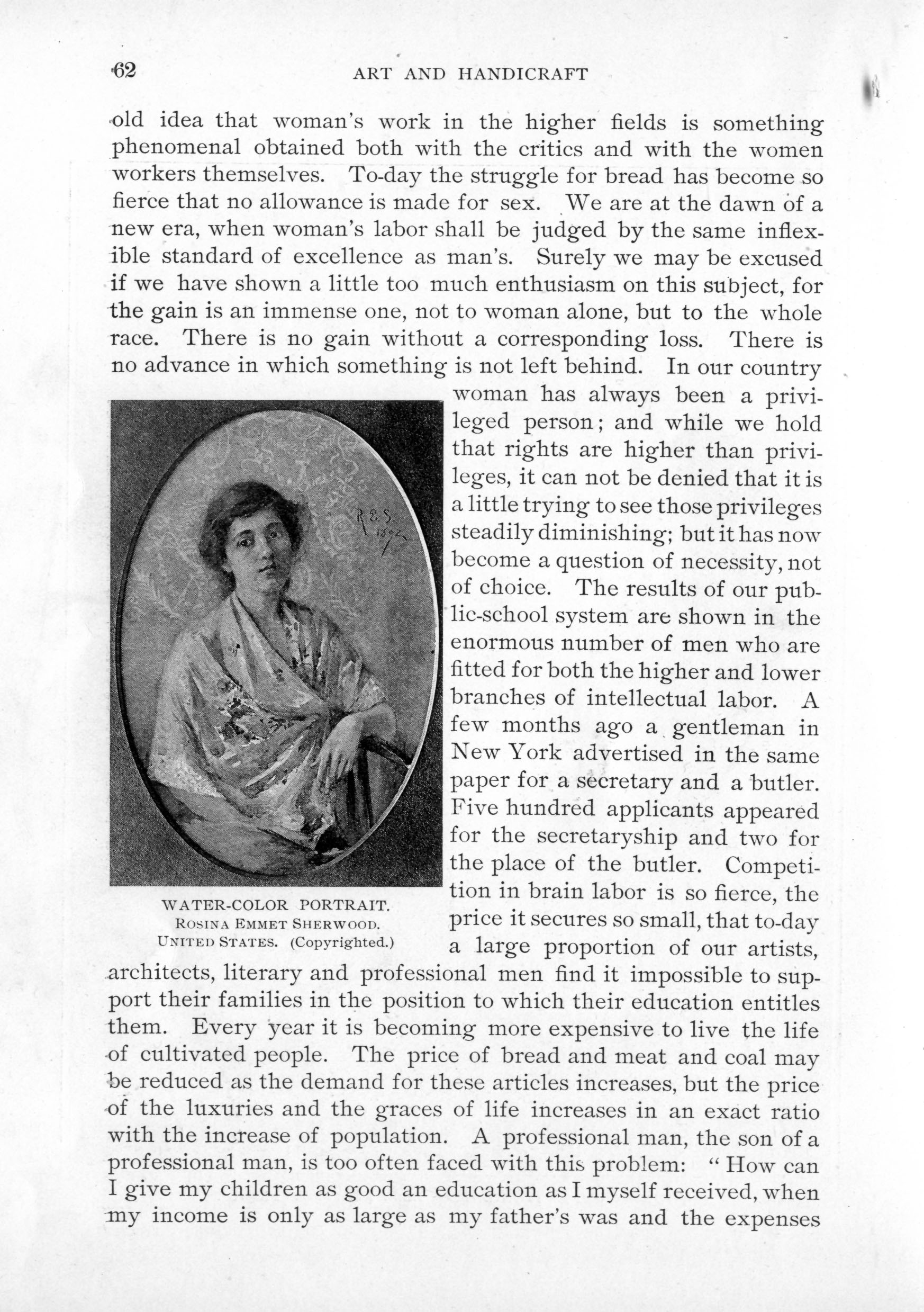

The pair of panels which are placed opposite to those just described are the work of those popular painters Rosina Emmet Sherwood and Lydia Emmet. Mrs. Sherwood's panel shows us the Republic welcoming her daughters and bestowing laurel crowns upon them. The composition of this panel is very good, and the architectural detail of the background is well studied. Miss Emmet's companion panel is strong in the same qualities as her sister's. Music, art, and literature are all personified in an exceedingly well-arranged group of female figures.

BLACK AND WHITE DRAWING—"ANON COMES APRIL IN HER JOLLITY."

ROSINA EMMET SHERWOOD. UNITED STATES.

(From Harper's Magazine. Copyrighted.)

I shall now invite the reader to take a short stroll with me through the principal departments of our building. We will enter at the northern door, pass through the loggia, and find ourselves in the midst of the American exhibit of applied arts. Here all is so excellent that we can afford to lose nothing; every case deserves examination. As it is impossible to speak of all the beautiful work exhibited by associations and individuals, let us notice that of the "Associated Artists," the parent society from which so many schools of embroidery and design have sprung. The two directions in which this school expresses itself are in the weaving of textiles and tapestries. The textiles are among the most beautiful fabrics that have ever been woven; they are rich in color and exquisite in texture. Certain effects can be produced by the weaving of silk which no pigment can ever give, for the silk itself has a reflective quality which is found in no other medium. The tapestry from Raphael's cartoon of "The Miraculous Draught of Fishes" is a very remarkable work of art, and one which stands alone in modern needlework. The design was photographed from the painter's cartoon upon the linen, and the spirit of the original is very perfectly preserved.

The pottery comes next in interest to the textiles and embroideries. Nowhere is woman doing better work than in the manufacture and decoration of our native clays. We find original and beautiful vessels of use and ornament exhibited by many of the States. It is due to the Western States to say that in this branch of applied arts they surpass the Eastern.

However long we linger in this section of the building, we leave it with regret. The impression which we carry away from it is that we are no longer pensioners of Europe in the matter of designs. To-day we have an American School of Design, with a distinct national character of its own, and our women are to the fore in every one of its branches.

Passing through the corridor we enter the main hall, where there is much to admire in exhibitions of art and handicraft. The laces, in themselves, are a gallery of exquisite design and workmanship. There is no danger that the visitor will slight the Hall of Honor, so we will not linger here, but pass on to the southern pavilion. We have crossed the seas, Spain is before us; India, Germany, Austria, Belgium are upon our left; Sweden, Mexico, Italy, France upon the right. Two rooms of a Japanese house have been cunningly reproduced with the nicety and finish which characterize all the work of this artistic people. The low-ceiled boudoir is

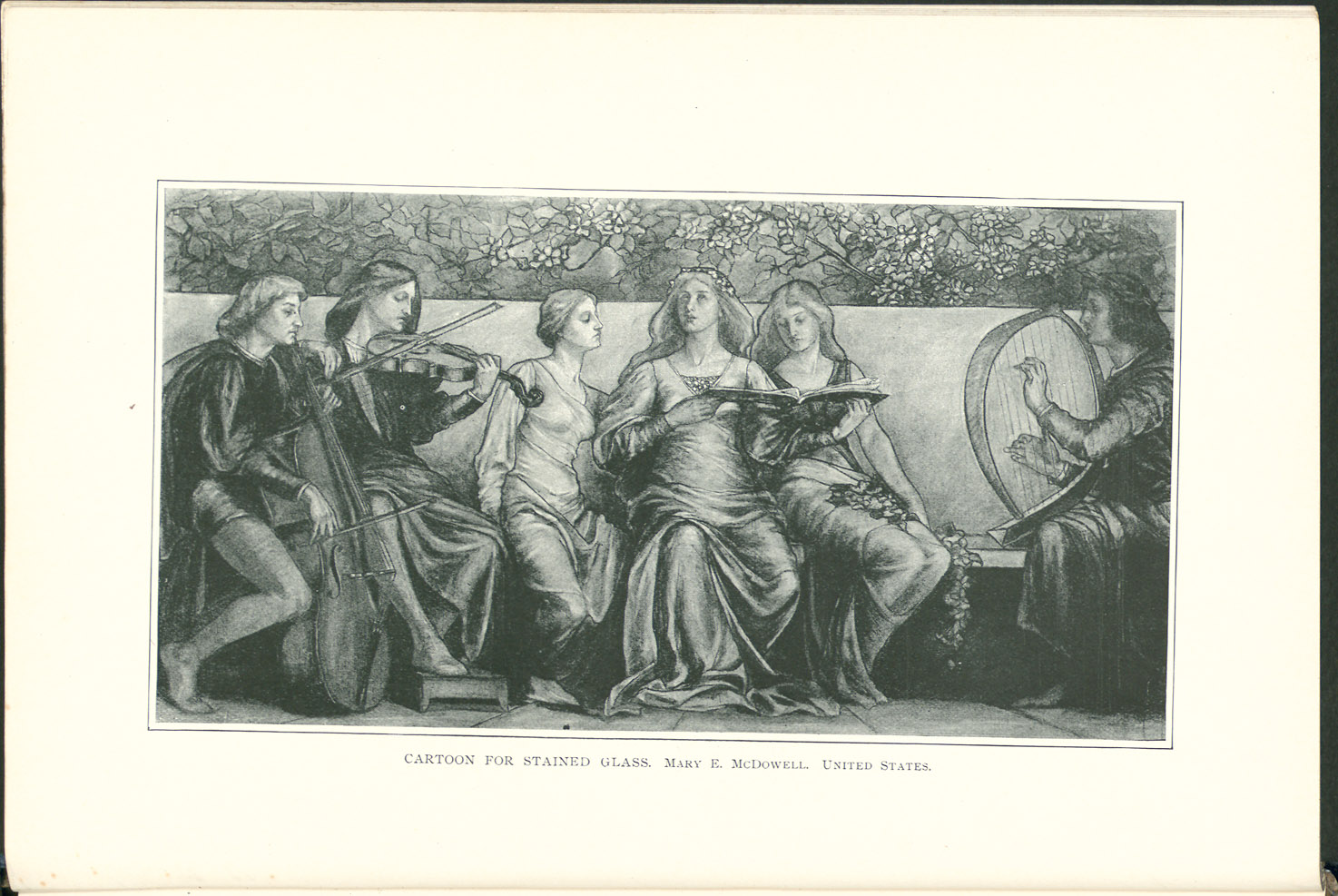

CARTOON FOR STAINED GLASS.

MARY E. MCDOWELL.

UNITED STATES.

carpeted with matting and hung with delicately tinted paper. In an outer room—a guest-chamber—is a raised cushion of state, on which the honored stranger is invited to sit (or squat). A few paintings hang upon the wall; a single piece of bronze, a finely modeled bird, rests on a lacquered stand. The inner room is sacred to the toilet of the lady of the house. Over a screen hang rainbow-hued garments enriched with wonderful embroideries. Lacquered coffers of every size and shape, tied with silk cords of different colors, form a picturesque substitute for our commonplace chests of drawers. A polished steel mirror, upon a stand, shows where the mistress of this dainty boudoir should sit upon a cushion to perform the details of her toilet. A lacquered and bronze brazier stands near, and a rack over which are folded fine linen towels. A multitude of fine inlaid boxes stand upon the ground near the mirror. Let us not pry into their secrets. The real secret of the peculiar charm which the Japanese women have always possessed for men of their own and the European nations lies in the fact that they are taught to be agreeable. With the Japanese, good manners rise to the dignity of a high art. Courtesy, gentleness, sympathy are cultivated with the same care and skill that this joyous, painstaking people put into everything that they do.

We must not fail to see the Japanese parlor in the second story, where the Japanese Commissioner has gathered together a very fine collection of painted and embroidered screens and hangings. A painting upon silk, framed in a little shrine in the end of this room, shows us Sei Shonagun, a learned Japanese woman who served the Empress Sada Ko in the tenth century of the Christian era. She wrote a book which is still famous, an extract from which we may read, in translation, together with a full description of the picture. Nothing brings home the real significance of the work collected in our building more than the statement made by the Japanese Woman's Commission of its organization. The report says: "Her Majesty the Empress of Japan, with her usual habits of helping any good work, especially for her own sex, most graciously pleased with the movement, generously bestowed a large gift to carry on the work of the commission. Princess Mori assumed the duty of chairman, and asked the members, who are mostly ladies of high rank, to act as committees. On the 13th of May, 1892, the first meeting of the commission was held at Shiba-Hama-Rikyn, a pleasure palace in Tokio. Since then, twice a month they have held regular meetings to consider the affairs of the commission."

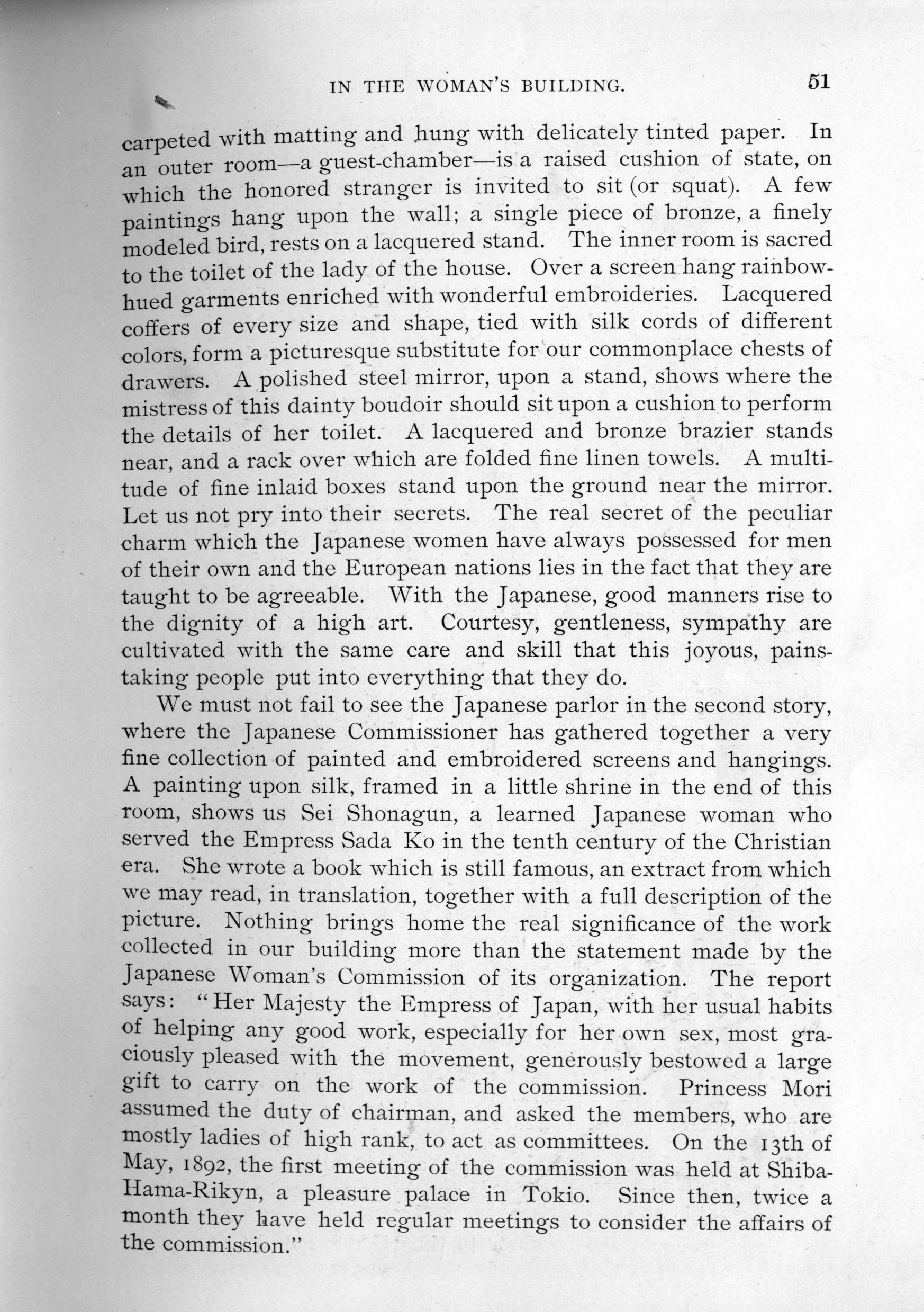

WATER-COLOR PORTRAIT.

ROSINA EMMET SHERWOOD.

UNITED STATES.

The most important feature of the second story is the Assembly Hall, a large room lying on the north side of the building. It has a wide platform and is admirably adapted for meetings, lectures, and concerts. The three stained-glass windows which light the stage are all the work and two of them the gifts, of Massachusetts women. The furniture, presented by the ladies' committee of Mobile, is simple and appropriate in design. A stained-glass window opposite the platform is the work and the gift of Pennsylvania women. It was in this room that the meeting was held on the 30th of April, when the commissioners from many of our own States and from some distant countries presented to Mrs. Palmer the gifts offered to the Woman's Building. Tokens and tidings of good-will from the four corners of the earth were generously offered and graciously accepted. The value of the gifts, the nationality of the givers, was forgotten in the deep significance of that meeting. Woman at last is rousing from her long sleep. We of the New World have called out for help, for sympathy. From the far Orient comes back an answer to our cry. The slave woman of the harem murmurs, "I hear!"

The Assembly Hall and the Model Kitchen fill the whole of the northern end of the building. The space between the inner corridor and the outer arcade has been divided into eight admirably-shaped and well-lighted rooms. The Model American Kitchen gives an object lesson to housekeepers from all parts of the world.

Passing down the corridor to the right we find Connecticut's

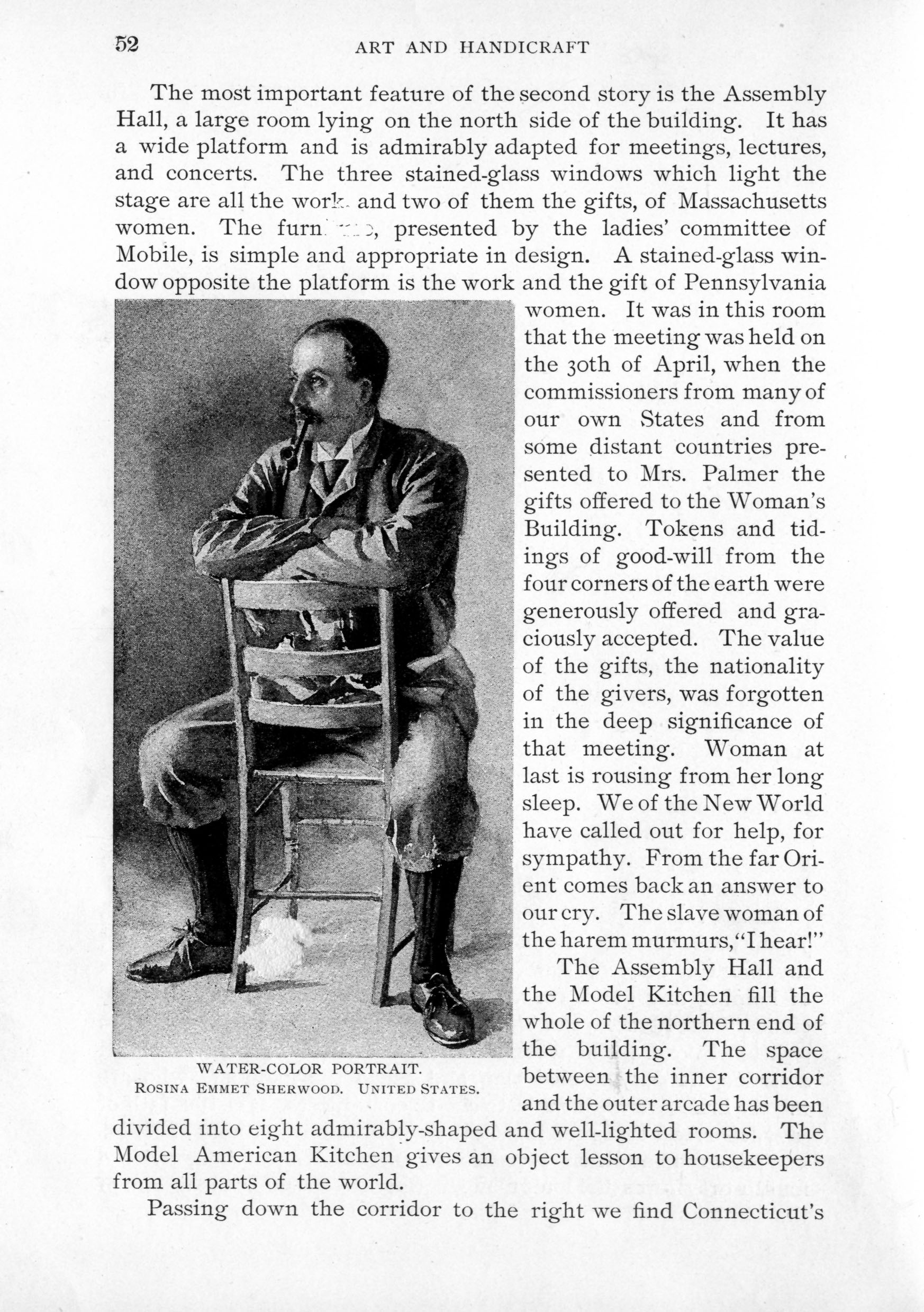

SKETCH FOR GLASS WINDOW.

MRS. PARRISH.

UNITED STATES.

room, a bright, cheerful apartment, whose simple and appropriate decoration we owe to Miss Sheldon of Hartford.

We come next to the first of the two Record rooms, which on either side connect with the library. Here are kept the statistics of woman's work in many countries, which have been collected with such patient research. A frieze formed of panels of native wood, designed and carved by women from our different States, is an interesting feature of this room.

From a purely artistic standpoint the library is the most important feature of the building, after the Hall of Honor. Its decoration has been intrusted to Mrs. Wheeler. As the heavy doors swing to, we find ourselves in a well-proportioned room, whose chief and most valued quality is that of harmony. The eyes, tired with the great demand which has been made upon them, rest gratefully upon the green and gold of the walls. The visitor sinks into a chair, and for a long time thinks of nothing but the pleasant coolness of the place. The room has a character and individuality that we rarely find save in the house of some esthetic lover of books. The beautiful dark carved-oak book-cases are filled to overflowing with books by women of all nations. Every room has its own climate—we know whether we are visiting in the arctic, the temperate, or the torrid zone five minutes after entering a strange house. Our library is in the temperate zone—the best climate for the scholar and the dilettante. To such a visitor there is no single apartment in the whole Fair where he will find himself so pleasantly at home. The chief decoration of this room is the ceiling—the work of Dora Wheeler Keith. In undertaking this arduous labor Mrs. Keith attacked the most difficult branch of decoration, and the artist is to be congratulated that she has painted what is perhaps the rarest thing in the whole range of art, a successful ceiling.

The ornamentation is rich and original. A wide border of scroll-work forms the outer edge. Inside of this we have a very beautifully painted piece of drapery, enriched here and there with

CARTOON FOR MEMORIAL WINDOW.

HELEN MAITLAND ARMSTRONG.

UNITED STATES.

bunches of lilies, which weaves itself into a sort of garland between the four medallions, each of which contains a symbolical figure. The oval wreath of lilies which encircles the central portion is a very beautiful and original feature of the decoration. The central group contains three figures. Science, a male figure, sits enthroned with Literature beside him, personified by a graceful woman; between the two stands Imagination, reconciling and binding Science and Literature to each other. The color scheme is cool, refreshing, and harmonious. In speaking of this admirable work, Mrs. Wheeler was heard to say: "I think it is a worthy composition." I have heard many more extravagant phrases applied to this decoration by connoisseurs and critics, but none has pleased me so much. It is indeed worthy of the honored name both mother and daughter bear—a name that is identified with such a potent influence for high taste, serious work, and honest endeavor. Among the founders of the new American school of design which has done so much for the education of our people, there is no figure more striking than that of Candace Wheeler.

Continuing our tour, we find ourselves in the room devoted to the exhibit of the English Training-School for Nurses. There is much that is valuable and interesting to study here; a wonderful basket trunk with compartments for caps and bandages, splints, bonnets, aprons, and all the other requisites for the personal comfort and professional duties of a soldier in the noble army of nurses. The room is graced with portraits of women whose names never fail to arouse an emotion when they are pronounced—Florence Nightingale, Sister Dora, and a score of other less famous sisters of humanity.

The Organization Room lies at the south end of the corridor. Here we may see the exhibit of over fifty associations of women. Opposite the library we have a suite of three rooms. The first of these, the Kentucky Parlor, is a very pleasant and cheerful room, with a flavor of the "old colonial" in its decoration and appointments.

We next pass into the Manager's Drawing-room, furnished, decorated, and maintained by the women of Cincinnati. It is a pleasant place to linger, and has many treasures of pottery and faience.

Beyond is the California Room, famous for its redwood. The ceiling, doors, and wainscoting are all made of this rich, mellow wood, the grain of which makes delicate lines and touches of light and color, which the high polish brings out finely.

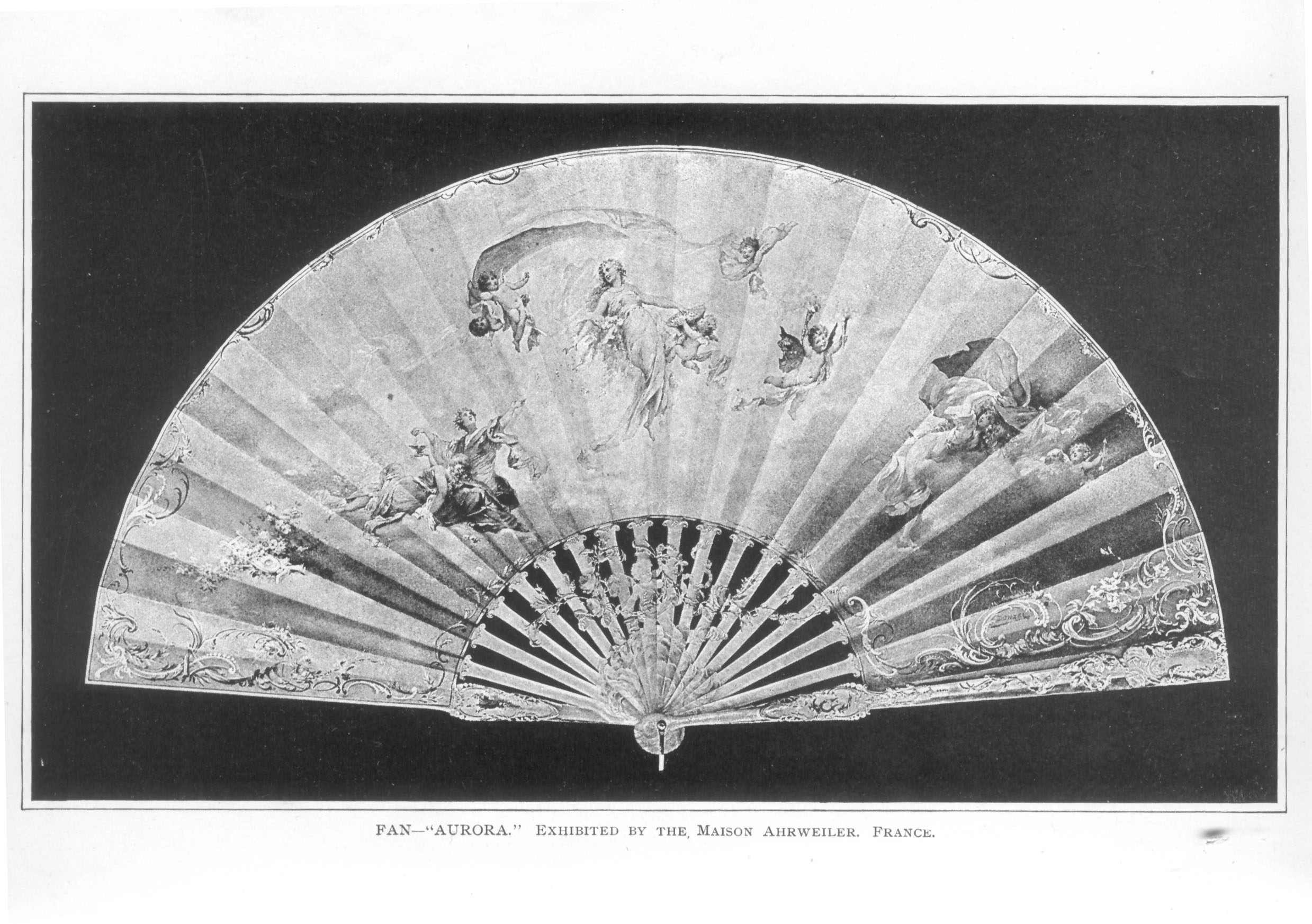

SKETCH FOR WINDOW.

MARY TILLINGHAST.

UNITED STATES.

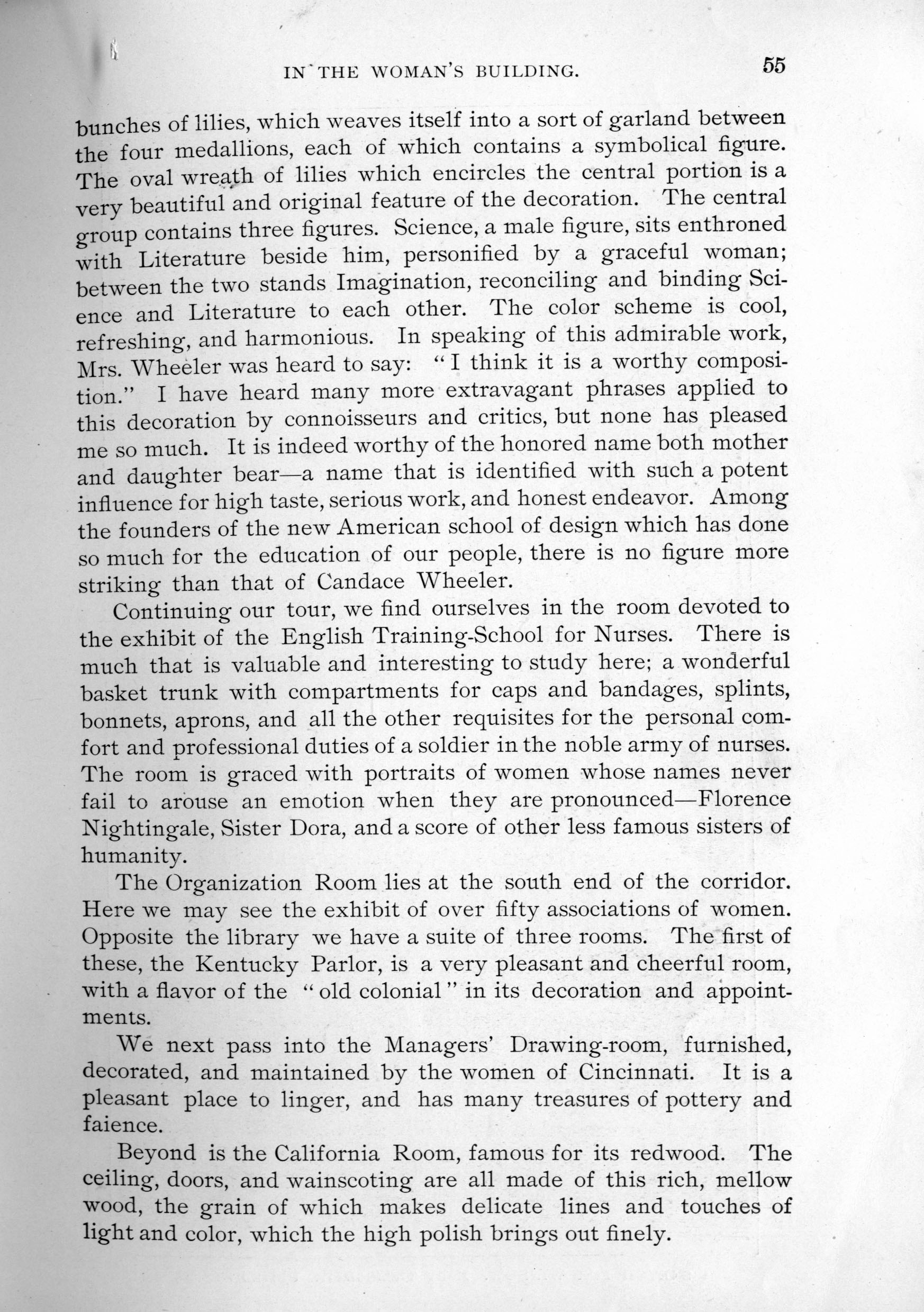

PAINTED SCREEN.

FRANCE.

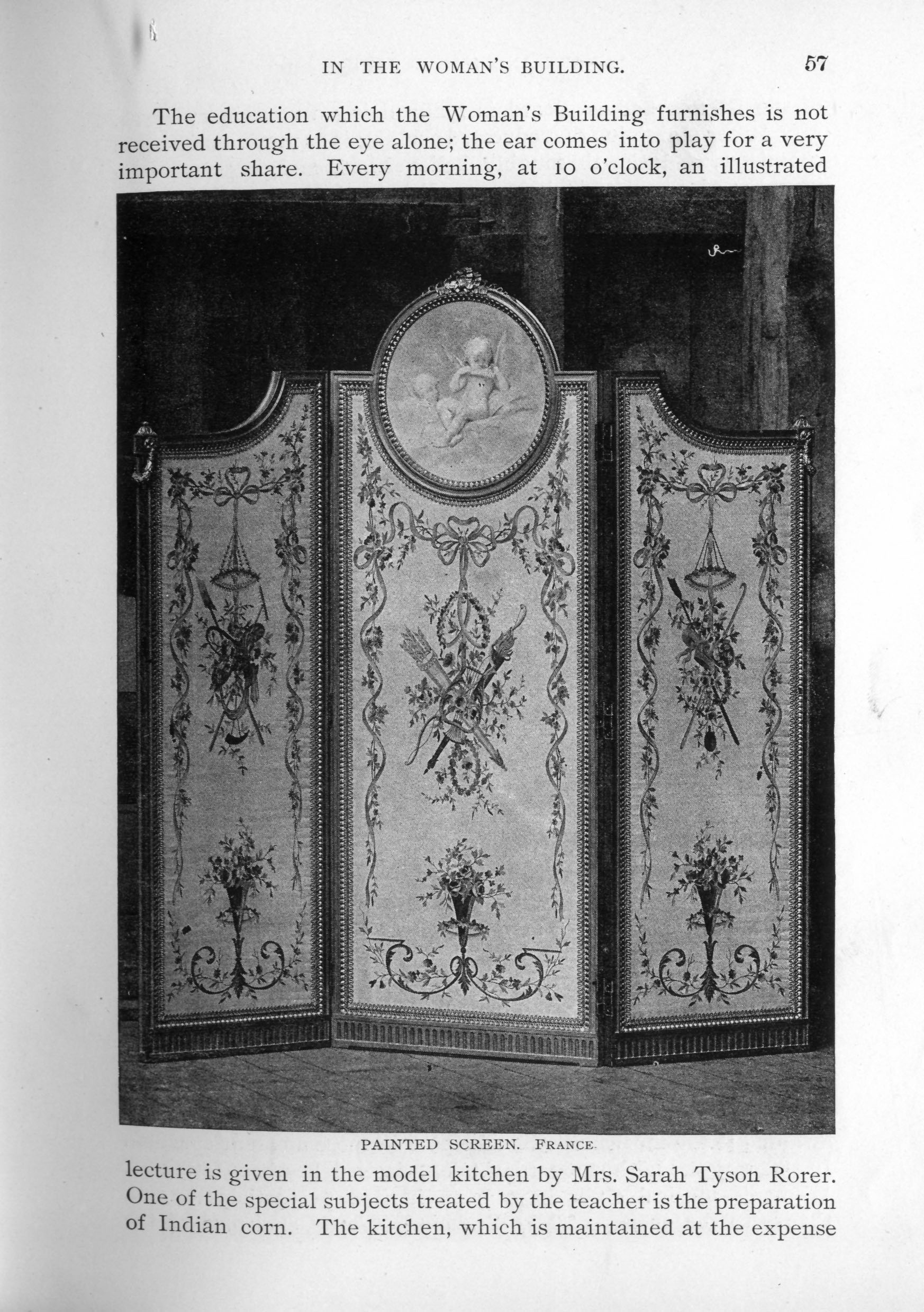

The education which the Woman's Building furnishes is not received through the eye alone; the ear comes into play for a very important share. Every morning, at 10 o'clock, an illustrated lecture is given in the model kitchen by Mrs. Sarah Tyson Rorer. One of the special subjects treated by the teacher is the preparation of Indian corn. The kitchen, which is maintained at the expense

of the Illinois Ladies' Board, is really doing a missionary work. Mrs. Rorer maintains that educated cooking is as much a science as chemistry, and she thoroughly believes in the saying that "the inventor of a new and wholesome dish is of greater value to his fellow-creatures than the discoverer of a new planet." Of all the pleasant features of our building, I have found nothing more interesting than these sessions with Mrs. Rorer. To hear the mysteries of baking, roasting, and boiling intelligently explained, and to watch at the same time the skillful preparation of a dainty dish, is a pleasant and instructive occupation. The infinite variety of forms into which the Indian corn can be transmuted by an intelligent cook was a revelation to most of Mrs. Rorer's hearers.

Another pleasant educational exhibit of a similar nature is to be found in the garden café, where Mrs. Riley, a graduate of the Boston Cooking School, provides home cooking of the most appetizing description for the hungry sight-seer, but opens her kitchen for public inspection every afternoon for an hour. The restaurant serves a double purpose—it feeds the hungry visitor and educates the inquiring mind of the housekeeper. The contrast between this well-ordered establishment, where the dishes are properly prepared and neatly served, and some of the other restaurants of the Fair is very striking. Nowhere is the tired man or woman so well treated and fed as in our model lunch-room.

The Committee of Congresses, of which Mrs. James P. Eagle is chairman, has prepared a feast of reason, in which the public is invited to participate. Either in the morning or the afternoon of each day the Assembly Room in the Woman's Building will furnish an amusement or lecture, which, like all the other matters connected with our building, is given to the public gratis. Music has an honored place in our temple. One afternoon of every week Mr. Theodore Thomas and his well-trained orchestra give a concert of popular classical music; it may be imagined that there is little room to spare in the Assembly Hall on these occasions. Once in every two weeks concerts are given by amateur musicians from different parts of the country. The method pursued in securing the performers is extremely good. The candidates first pass an examination in their own State, and then a second at Chicago before a jury of experts appointed by Mr. Thomas. A diploma will be awarded to the musicians who take part in these amateur concerts. In this way the high standard of talent desired has been attained. Women's musical clubs have been invited to participate, and thanks to the energy of Mrs. Francis B. Clarke, chairman of the

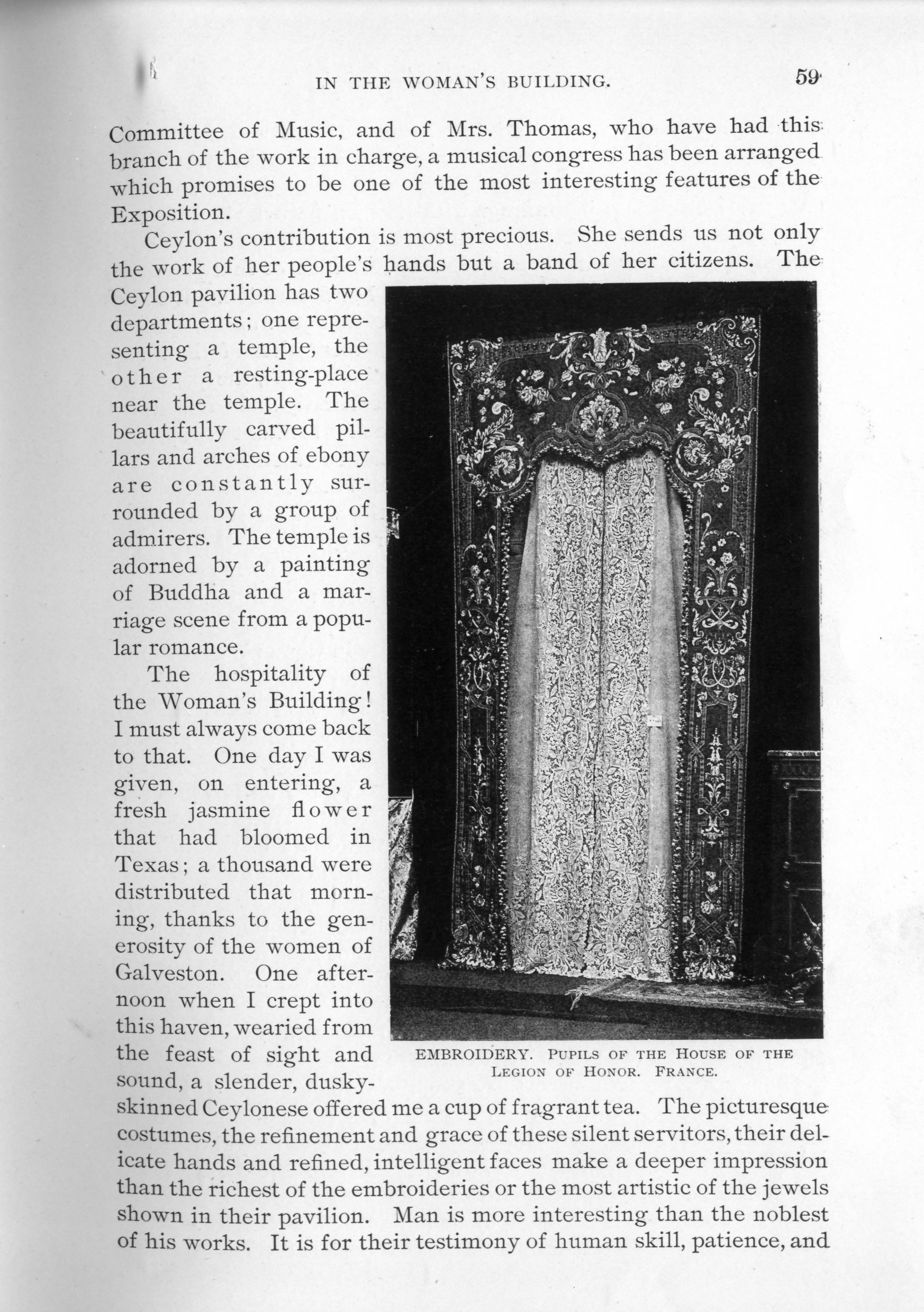

EMBROIDERY.

PUPILS OF THE HOUSE OF THE LEGION OF HONOR. FRANCE.

Committee of Music, and of Mrs. Thomas, who have had this branch of the work in charge, a musical congress has been arranged which promises to be one of the most interesting features of the Exposition.

Ceylon's contribution is most precious. She sends us not only the work of her people's hands but a band of her citizens. The Ceylon pavilion has two departments; one representing a temple, the other a resting-place near the temple. The beautifully carved pillars and arches of ebony are constantly surrounded by a group of admirers. The temple is adorned by a painting of Buddha and a marriage scene from a popular romance.

The hospitality of the Woman's Building! I must always come back to that. One day I was given, on entering, a fresh jasmine flower that had bloomed in Texas; a thousand were distributed that morning, thanks to the generosity of the women of Galveston. One afternoon when I crept into this haven, wearied from the feast of sight and sound, a slender, dusky-skinned Ceylonese offered me a cup of fragrant tea. The picturesque costumes, the refinement and grace of these silent servitors, their delicate hands and refined, intelligent faces make a deeper impression than the richest of the embroideries or the most artistic of the jewels shown in their pavilion. Man is more interesting than the noblest of his works. It is for their testimony of human skill, patience, and

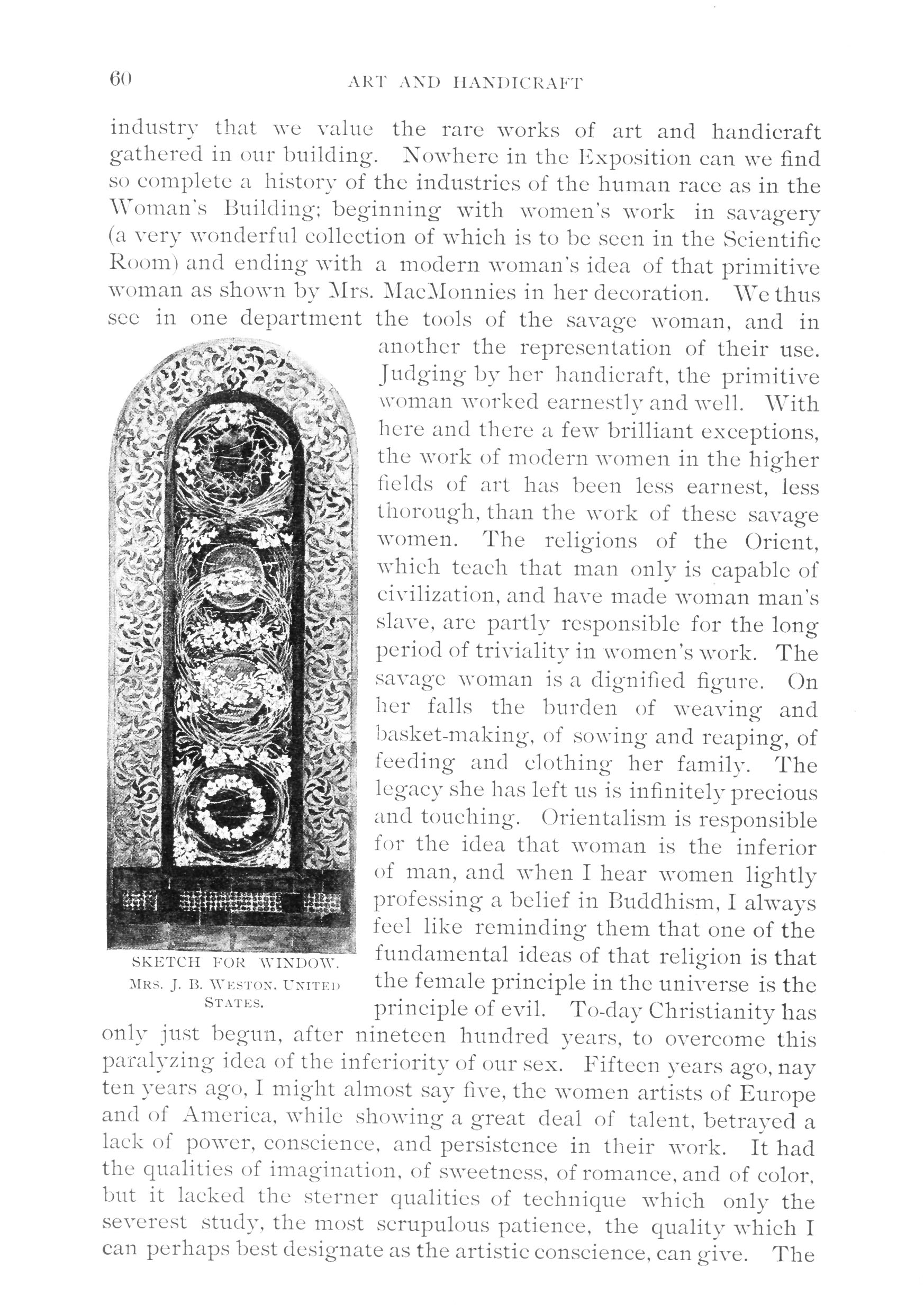

SKETCH FOR WINDOW.

MRS. J. B. WESTON.

UNITED STATES

industry that we value the rare works of art and handicraft gathered in our building. Nowhere in the Exposition can we find so complete a history of the industries of the human race as in the Woman's Building; beginning with women's work in savagery (a very wonderful collection of which is to be seen in the Scientific Room) and ending with a modern woman's idea of that primitive woman as shown by Mrs. MacMonnies in her decoration. We thus see in one department the tools of the savage woman, and in another the representation of their use. Judging by her handicraft, the primitive woman worked earnestly and well. With here and there a few brilliant exceptions, the work of modern women in the higher fields of art has been less earnest, less thorough, than the work of these savage women. The religions of the Orient, which teach that man only is capable of civilization, and have made woman man's slave, are partly responsible for the long period of triviality in women's work. The savage woman is a dignified figure. On her falls the burden of weaving and basket-making, of sowing and reaping, of feeding and clothing her family. The legacy she has left us is infinitely precious and touching. Orientalism is responsible for the idea that woman is the inferior of man, and when I hear women lightly professing a belief in Buddhism, I always feel like reminding them that one of the fundamental ideas of that religion is that the female principle in the universe is the principle of evil. To-day Christianity has only just begun, after nineteen hundred years, to overcome this paralyzing idea of the inferiority of our sex. Fifteen years ago, nay ten years ago, I might almost say five, the women artists of Europe and of America, while showing a great deal of talent, betrayed a lack of power, conscience, and persistence in their work. It had the qualities of imagination, of sweetness, of romance, and of color, but it lacked the sterner qualities of technique which only the severest study, the most scrupulous patience, the quality which I can perhaps best designate as the artistic conscience, can give. The

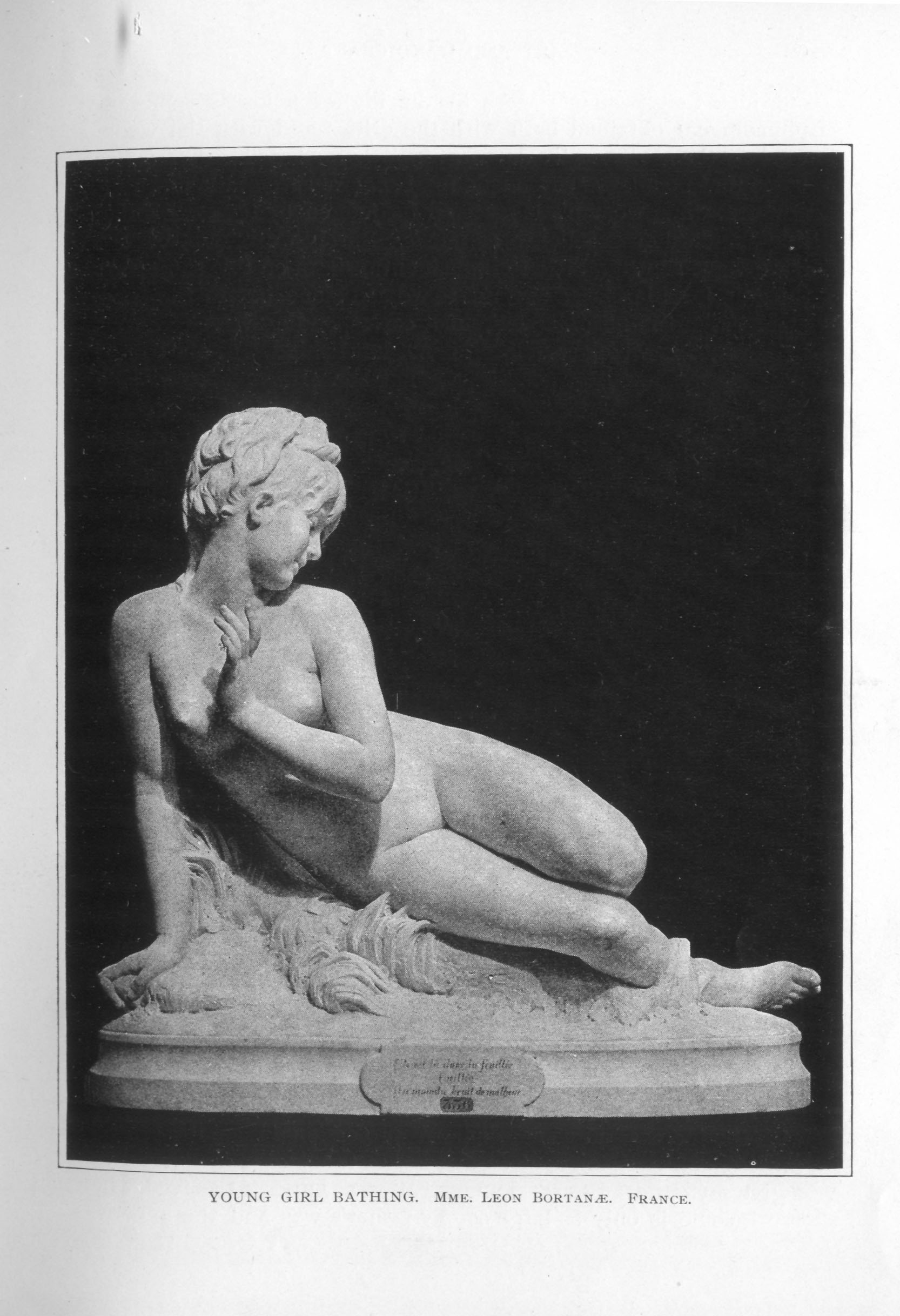

YOUNG GIRL BATHING.

MME. LEON BORTANÆ.

FRANCE.

WATER-COLOR PORTRAIT.

ROSINA EMMET SHERWOOD.

UNITED STATES. (Copyrighted.)

old idea that woman's work in the higher fields is something phenomenal obtained both with the critics and with the women workers themselves. To-day the struggle for bread has become so fierce that no allowance is made for sex. We are at the dawn of a new era, when woman's labor shall be judged by the same inflexible standard of excellence as man's. Surely we may be excused if we have shown a little too much enthusiasm on this subject, for the gain is an immense one, not to woman alone, but to the whole race. There is no gain without a corresponding loss. There is no advance in which something is not left behind. In our country woman has always been a privileged person; and while we hold that rights are higher than privileges, it can not be denied that it is a little trying to see those privileges steadily diminishing; but it has now become a question of necessity, not of choice. The results of our public-school system are shown in the enormous number of men who are fitted for both the higher and lower branches of intellectual labor. A few months ago a gentleman in New York advertised in the same paper for a secretary and a butler. Five hundred applicants appeared for the secretaryship and two for the place of the butler. Competition in brain labor is so fierce, the price it secures so small, that to-day a large proportion of our artists, architects, literary and professional men find it impossible to support their families in the position to which their education entitles them. Every year it is becoming more expensive to live the life of cultivated people. The price of bread and meat and coal may be reduced as the demand for these articles increases, but the price of the luxuries and the graces of life increases in an exact ratio with the increase of population. A professional man, the son of a professional man, is too often faced with this problem: "How can I give my children as good an education as I myself received, when my income is only as large as my father's was and the expenses

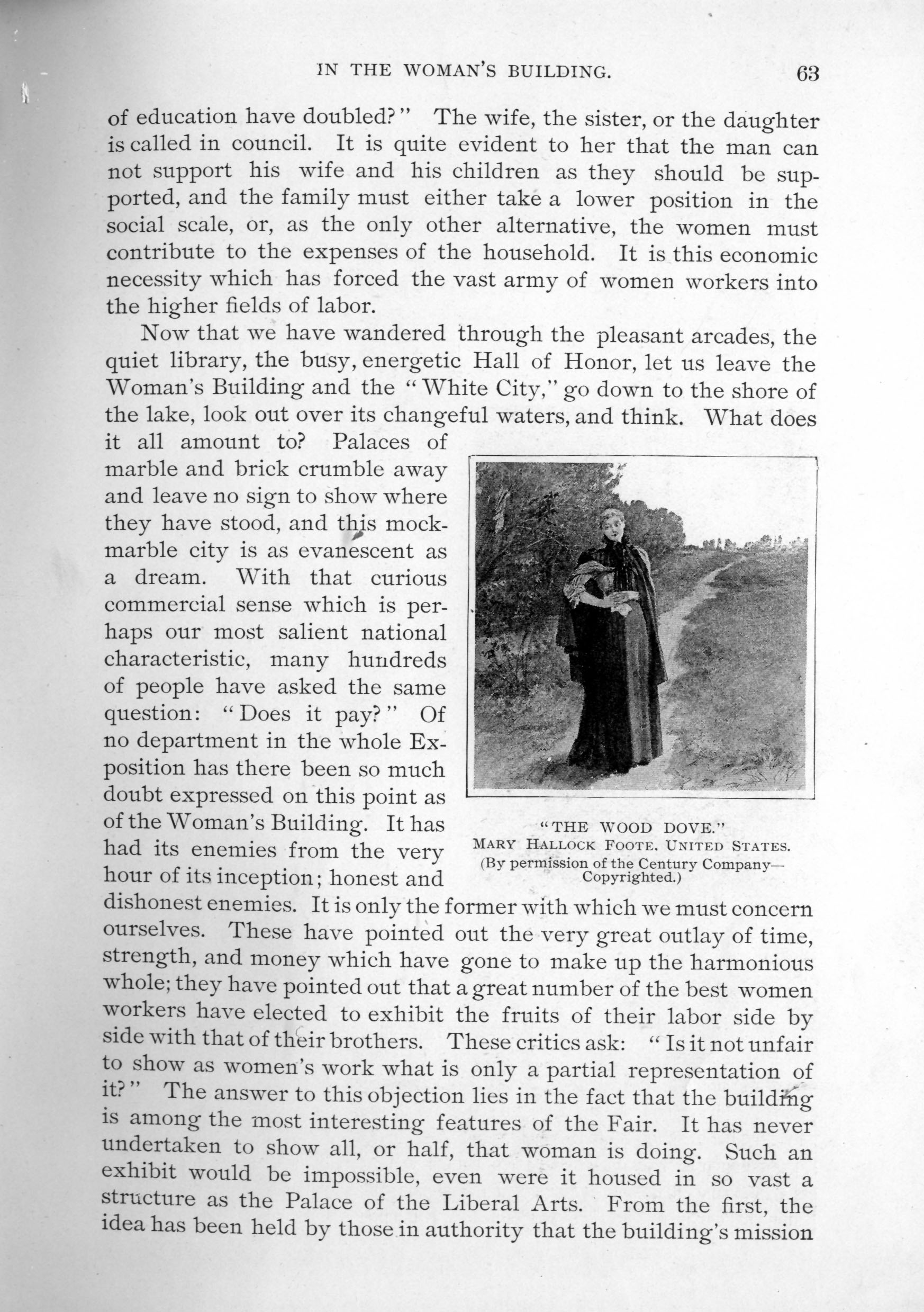

"THE WOOD DOVE."

MARY HALLOCK FOOTE.

UNITED STATES.

(By permission of the Century Company—Copyrighted.)

of education have doubled?" The wife, the sister, or the daughter is called in council. It is quite evident to her that the man can not support his wife and his children as they should be supported, and the family must either take a lower position in the social scale, or, as the only other alternative, the women must contribute to the expenses of the household. It is this economic necessity which has forced the vast army of women workers into the higher fields of labor.

Now that we have wandered through the pleasant arcades, the quiet library, the busy, energetic Hall of Honor, let us leave the Woman's Building and the "White City," go down to the shore of the lake, look out over its changeful waters, and think. What does it all amount to? Palaces of marble and brick crumble away and leave no sign to show where they have stood, and this mock-marble city is as evanescent as a dream. With that curious commercial sense which is perhaps our most salient national characteristic, many hundreds of people have asked the same question: "Does it pay?" Of no department in the whole Exposition has there been so much doubt expressed on this point as of the Woman's Building. It has had its enemies from the very hour of its inception; honest and dishonest enemies. It is only the former with which we must concern ourselves. These have pointed out the very great outlay of time, strength, and money which have gone to make up the harmonious whole; they have pointed out that a great number of the best women workers have elected to exhibit the fruits of their labor side by side with that of their brothers. These critics ask: "Is it not unfair to show as women's work what is only a partial representation of it?" The answer to this objection lies in the fact that the building is among the most interesting features of the Fair. It has never undertaken to show all, or half, that woman is doing. Such an exhibit would be impossible, even were it housed in so vast a structure as the Palace of the Liberal Arts. From the first, the idea has been held by those in authority that the building's mission

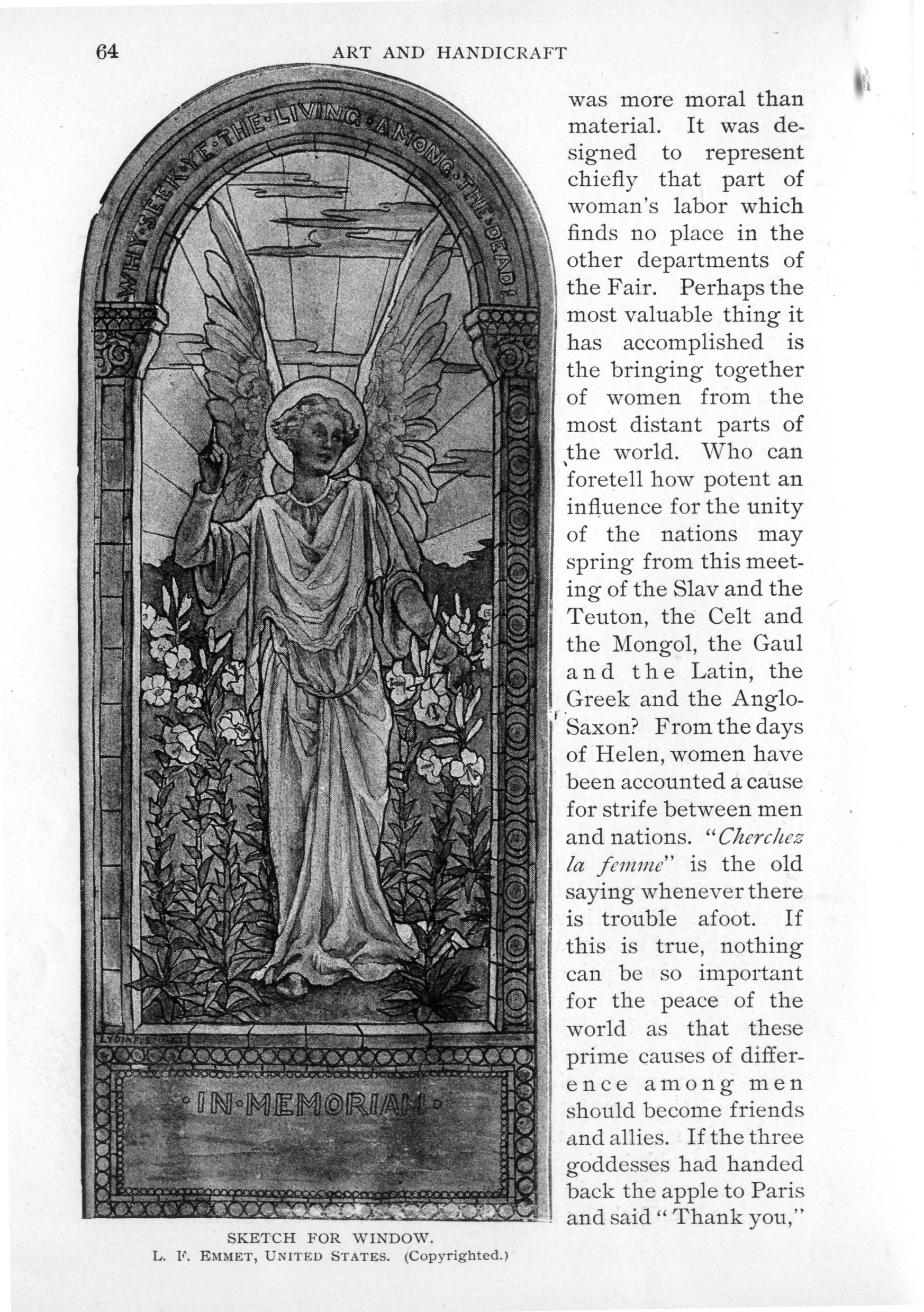

SKETCH FOR WINDOW.

L. F. EMMET, UNITED STATES. (Copyrighted.)

was more moral than material. It was designed to represent chiefly that part of woman's labor which finds no place in the other departments of the Fair. Perhaps the most valuable thing it has accomplished is the bringing together of women from the most distant parts of the world. Who can foretell how potent an influence for the unity of the nations may spring from this meeting of the Slav and the Teuton, the Celt and the Mongol, the Gaul and the Latin, the Greek and the Anglo-Saxon? From the days of Helen, women have been accounted a cause for strife between men and nations. "Cherchez la femme" is the old saying whenever there is trouble afoot. If this is true, nothing can be so important for the peace of the world as that these prime causes of difference among men should become friends and allies. If the three goddesses had handed back the apple to Paris and said "Thank you,"

a mighty pother of arms might have been saved and the greatest poem in the world lost. In our modern contest, each participant strives not to take from but to give to her sisters the palm. In many of the other departments of the Fair there has been an infinite amount of political friction. One country will not exhibit because our duties are unjust, another will put itself to very little trouble for us because it has so little commercial relation with our own. We find nothing of this in the Woman's Building. We find a singleness of purpose which is truly impressive. The queens of England, of Spain, and of Italy take part in our enterprise; the empresses of Japan and of Russia testify their interest; the wife of the president of the French Republic lends us her countenance, and the great ladies of Germany, Belgium, Sweden, Norway, Denmark, Russia, Austria, and all the other nations represented in our building have put their hands to our work.

The Queen of England, her daughters, and her granddaughters send us their handiwork. Not only have the great ladies lent us their countenance, but the work-women all over the world have helped to enrich our building. In the Spanish section we notice the neatly rolled cigarettes of the cigarette-makers and the nets of the fisher-wives lying near the rich embroideries of the nuns, the exquisite missals from the convent schools, the paintings and writings of royal amateurs. The insane women of a Pennsylvania almshouse make a contribution of neatly embroidered linen to our applied arts. The little children of the charity schools of Paris send us drawings and maps of so exquisite a workmanship that it is difficult to realize that the signatures, "Rachel, aged 13," and "Helene, aged 14," belong to their authors.

Many lessons may be learned at the World's Fair, and many in the Woman's Building; the most important of these is the unity of human interests. No man or woman who has truly entered into the life of the White City, which is not Chicago's, nor the United States', nor the Americas', but the world's city, can ever again be satisfied with mere city or State citizenship. In this miniature world we have tasted world's citizenship, we have learned that nothing that is not for the good of humanity at large can benefit us or our country.

MAUD HOWE ELLIOTT.

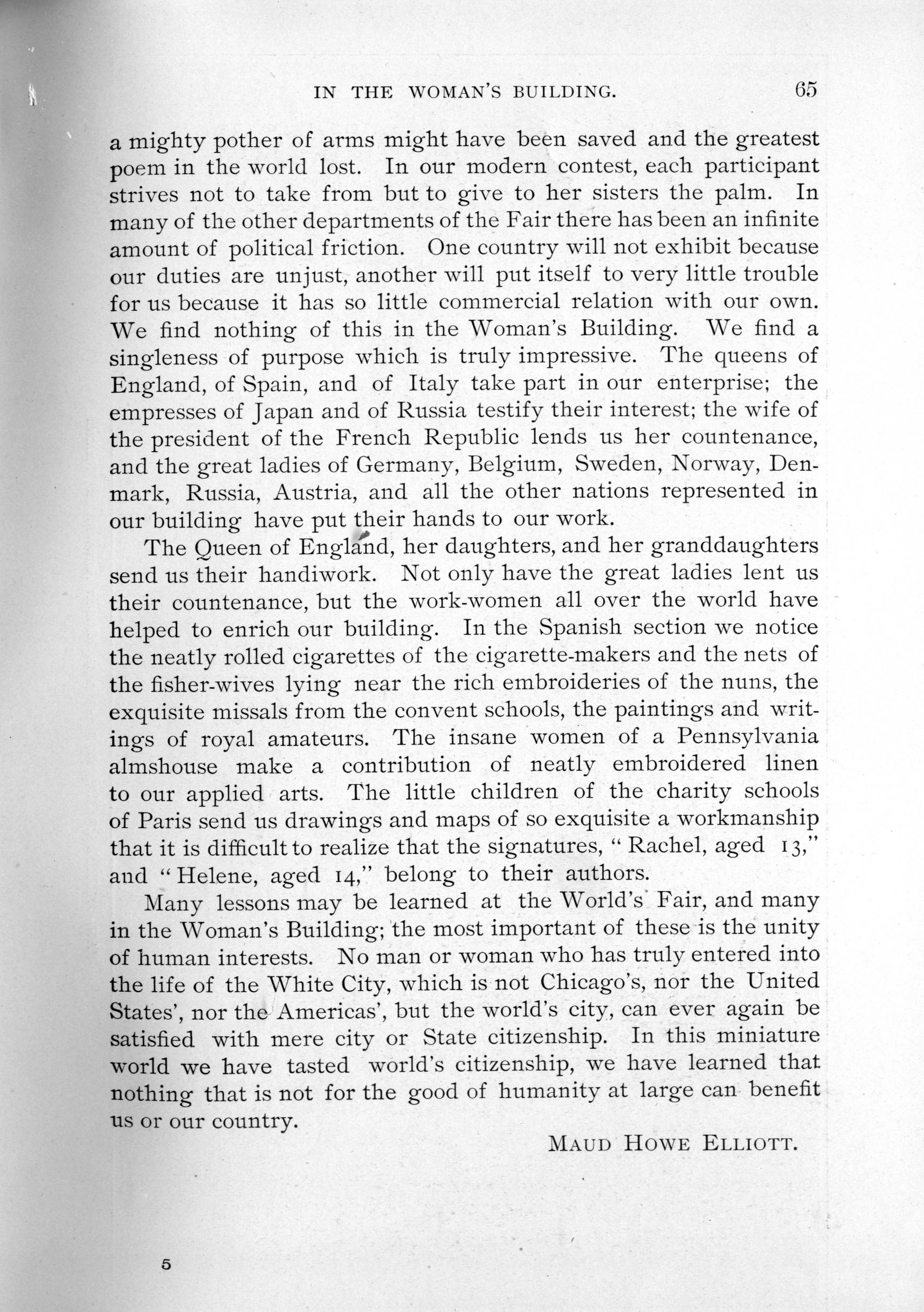

FAN—"AURORA."

EXHIBITED BY THE MAISON AHRWEILER. FRANCE.