CHAPTER III

EARLY ENGLISH DIALS

"Theodore arrived at his church the second year after his consecration (A.D. 669). Soon after, he visited all the island, wherever the tribes of the Angles inhabited, for he was willingly entertained and heard by all persons; and everywhere attended and assisted by Hadrian, he taught the right rule of life and the canonical custom of celebrating Easter. This was the first archbishop whom all the English church obeyed. And forasmuch as both of them were well read both in sacred and secular literature, they gathered a crowd of disciples, and there daily flowed from them rivers of knowledge to water the hearts of their hearers; and, together with the books of holy writ, they also taught them the arts of ecclesiastical poetry, astronomy, and arithmetic." — BEDE, Eccles. Hist., bk. iv., ch. 2.

IN the churchyard of Bewcastle in Cumberland, not far from the Scottish border, there stands a monolith 14 ½ feet high, the shaft of a fine cross. The head of the cross, which added another 2 ½ feet to the height, is lost, having been blown down some three centuries ago, when, instead of being replaced, it was sent to Lord William Howard, the warden of the Marches, who was a collector of antiquities, and it cannot now be traced. The sides of the shaft are covered with sculpture, both figures and ornamental designs, in high relief, and of great beauty and excellence. The base and angles are covered with runes, and on the south side, between panels of foliage and interlaced bands, there is a sun-dial. The date of this noble cross shaft is A.D. 670. Its history is told by the inscriptions, which have been deciphered and thus interpreted by the present Bishop of Bristol:

+ THIS SIGBEEN THUN SETTON HWAETRED WOTHGAR OLWFWOLTHU AFT ALCHFRITHU EAN KÜNING EAC OSWIUNG + GEBID HEO SINNA SOWHULA.

[This thin sign of victory Hwaetred Wothgar Olwfwolthu set up after (in memory of) Alchfrith once king and son of Oswy. Pray for the high sin of his soul.]

On the south side is the date:

[Full Image]

BEWCASTLE CROSS.

FRUMAN GEAR — KÜNINGES — RICES THAEES — ECGFRITHU. [First year of the king of this realm Ecgfrith.]

On the north side the names:

KÜNNBURUG, KÜNESWITHA, MÜRCNA KÜNG WULFHERE. [Cyniburga, Cyneswitha, King of Mercians Wulfhere.]

Above are three crosses, and the sacred name Gessus = Jesus.

Thus, as Bishop Browne tells us, we have here the earliest English sepulchral inscription, the earliest piece of English literature, and, we may add, the earliest English sun-dial.

With regard to Alchfrith, it is enough to remember that he was king of Deira under his father Oswy, and at one time a strong supporter of the Iona missionaries, who, from their settlement at Lindisfarne, had converted the pagan Angles of Northumbria and Mercia to Christianity. Afterwards, through the persuasions of the king of Wessex, Alchfrith was drawn to the Roman party, and Wilfrith became his friend. What special "high sin" it was that was laid on his soul we shall never know. The other names on the cross are those of the princes who chiefly served the cause of English Christianity in the seventh century. Wulfhere was an actively Christian ruler; Cyneberga and Cyneswitha were his sisters; the former was the widow of Alchfrith, and both were benefactresses to the Church. The name of Cyneswitha was also borne by Wulfhere's

mother, who was probably still living at that time. Oswy is called by Bede "the wise king and worshipper of God," and Alchfrith was his fellow-labourer in the same cause. The beautiful ornamental sculpture on the sides of the shaft stands in close relation with Byzantine art, and suggests the presence of a foreign designer, whose teaching the artistic Angles were quick to assimilate. 1

This indication of Greek influence is of special interest. It will be noticed that the dial on the Bewcastle Cross is drawn in the same semicircular form as those at Borcovicium, Orchomenes, and Herculaneum; and possibly the connection may be traced through the lessons in astronomy given to the Angles by the archbishop. Theodore, who was himself a Greek, was accompanied by Hadrian, a monk whose life had been passed in that part of Italy which was peopled by the descendants of Greeks, saturated with Greek ideas, and at that time the special refuge of cultivated Greeks who had been driven out of their own country. Or if no foreign artist had accompanied the archbishop, there was no man more likely to have invited one to England than the eager Wilfrith, in memory of whose friend and patron this monument was reared, and who was at that time Bishop of Northumbria and in favour with Wulfhere of Mercia.

The dial, which is at some height from the ground, is divided by five principal lines into four spaces, according to the octaval system of the Angles. Two of these lines, viz., those for 9 a.m. and midday, are crossed at the point. The four spaces are subdivided so as to give the twelve-day hours of the Roman and ecclesiastical use. On one side of the dial there is a vertical line which touches the semicircular border at the second afternoon hour. This may be an accident, but the same kind of line is found on the dial in the crypt of Bamburgh church, where it marks a later hour of the day.

There are a great many early dials on churches, especially in the north of England, but only a few of these can be confidently assigned to a pre-Conquest date. The number of spaces into which they are divided varies unaccountably. The late Dr. Haigh found an explanation, as we have seen, in the different time systems which prevailed amongst the various tribes by whom England was conquered — Jute, Saxon, Angle, Norse, Danish. Other archæologists have considered that the main divisions, and probably the crossed lines, marked the five canonical hours of the day, viz.: Prime, 6 a.m.; Tierce, 9 a.m.; Sext, noon; Nones, 3 p.m.; Vespers, 6 p.m.; the intermediate lines

1 "The Conversion of the Heptarchy," by the Right Rev. G. F. Browne.

[Full Image]

ESCOMBE.

PITTINGTON.

having probably been added for secular uses. The unequal or temporary hours were still in use when these dials were made. Bede states that "the hours were shorter or longer according to the season," and this method of reckoning lasted for several centuries. As the gnomon seems to have been placed horizontally, the dials could not have told the time with accuracy except at the equinox, but the hour of noon would always be shown, and possibly most country people would, from their own observation of the sun's position, be able to guess to a certain extent at the amount of error in the shadow.

The early dials are almost always semicircular; and circular dials, especially when they are completely rayed, may generally be considered mediæval. In conjecturing the probable date of a dial the quality of the stone as well as the style of architecture of the building must be taken into consideration. Unless the stone were hard it could not endure exposure to the sun on the south wall of a church, nor the effects of frost, for more than a few centuries. Nor is the probable date of a building conclusive evidence. Many dials have been cut on church walls long after the church itself was built. Others have been added during a reconstruction a hundred years or so after the original foundation. A few specimens of early date have been built into later walls, as is shown by the position in which they have ignorantly been placed. When we see a dial stone remaining where it was placed at the first building of the church it is an object of special interest. One of these few is on the pre-Conquest church of Escombe, near Bishop Auckland. It is on the south wall, at some height from the ground, and sheltered by a dripstone. The lines appear to divide the day into four parts, and the gnomon hole remains. There is a semi-circular dial also at Hart Church in the same county. This is divided into eight spaces. Another is built into the chancel wall at Middleton St. George, a

[Full Image]

ST. CUTHBERT'S, DARLINGTON.

fourth on the Norman church of Pittington. Here the dial shows six divisions of the day, with the midday line crossed. At Hamsterley Church there is a circle with a central hole, but no hour lines; and at Staindrop the broken half of a semicircular dial which seems to have shown four day-divisions. In the choir of St. Cuthbert's, Darlington, a dial stone is built into the wall. This is circular, and divided into eight spaces, with four outer and two inner rings, and a curious kind of cross mark in one of the spaces. There are some remains of a dial on an interior wall of St. Andrew's Church at Dalton-le-dale; only the numerals I to VII are to be seen now, and these are raised in relief upon the plaster, and are said to conceal an older set of figures. The hours would be shown when the sun shone through the south window. A set of numerals, much defaced by age, were also round the head of the tower door at Easington Church.

From these examples of early church dials which have been noticed in the county of Durham, we pass to Yorkshire, where there are several remarkable specimens; the inscribed stones of the Saxon period being especially valuable.

Perhaps the earliest of these is over the south door of the church of Weaverthorpe, in the East Riding. It is semicircular, and divided into twelve spaces, every alternate line being crossed. The inscription is:

+ IN HONORE : SCE : ANDREAE APOSTOLI : HEREBERTVS WINTONIE : HOC MONASTERIVM FECIT : IN TEMPORE REGN . . . [In honour of St. Andrew. Apostle, Herebert of Winchester made this monastery, in the time of Regn . . .]

The incomplete name is thought to be that of Regnald II., a Danish king of Northumbria, to whom King Eadmund of England stood godfather at his confirmation in 943. "The next year," says the Chronicle, "Eadmund subdued all Northumbria and expelled two kings, Anlaf son of Sihtric and Regnald son of Guthforth." From this one would conclude that the dial was set up before 944, but

[Full Image]

WEAVERTHORPE.

Dr. Haigh, who read the broken half line above the inscription as "OSCESTULI ARCHEPISCOPI," inferred that Regnald might have returned to his kingdom as Anlaf did, and if so, the date of the dial would be some fifteen or twenty years later. Oscestul, or Oskytul, became Archbishop of York in 956, and was a great restorer and reformer of monasteries. Herebert of Winchester was no doubt the abbot of the restored community, but what buildings he erected were in their turn destroyed by the Normans, for Doomsday Book records Weaverthorpe as "waste."

The dial at Kirkdale, in the North Riding, has been frequently noticed, but its completeness and importance deserve a special description. A great part of the church is of pre-Conquest times, and the dial must have been placed in its present position over the south door when the church was rebuilt in the eleventh century. The whole stone is 7 feet long by nearly 2 feet high, the dial being in the centre; the five greater lines which mark the central points of each tide are crossed, and the spaces between them halved by smaller lines, the whole being enclosed in a half circle, thus dividing the day into eight portions. The index line for the first tide of day, 7 ½ a.m., is marked by a × .

The inscription is given as interpreted by the Rev. D. H. Haigh, and the contractions supplied in smaller letters.

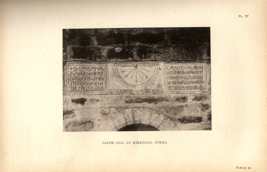

[Full Image]

SAXON DIAL AT KIRKDALE, YORKS.

+ ORM GAMALSVNA BOHTE Sanctus GREGORIVS MINSTER ÐONNE HIT WES ÆL TOBROCAN AND TOFALAN AND HE HIT LET MACAN NEWAN FROM GRVNDE CHristE AND Sanctus GREGORIVS IN EADWARD DAGVM CyniNG AND iN TOSTI DAGVM EORL.

+ THIS IS DAGES SOLMERCA ÆT ILCVM TIDE.

AND HAWARÐ ME WROHTE AND BRAND PRæpositus.[Orm Gamalson bought St. Gregory's minster when it was all utterly broken and fallen, and he it let make anew from ground to Christ and St. Gregory in Eadward (his) days King and in Tosti (his) days Earl.

This is (the) day's sun marker at every tide.

And Hawarth me wrought and Brand Provost.](Or as others read, Presbyter.)

The date of the rebuilding of this monastery may be fixed between 1063, the year in which Orm's father, Gamal Ormson, was treacherously murdered by Earl Tosti, and 1065, when the latter was deposed and banished. It is possible that this Provost (or Prior) Brand is the same who was elected Abbot of Peterborough in 1096, and Hawarth may have been his superior, and abbot of the newly-restored monastery of Kirkdale. The name of Brand may also have belonged to the district, as there is a dale called Bransdale not many miles away to the north. Tosti, the unworthy brother of King Harold, was made Earl of Northumberland on the death of Siward in 1056, and was slain at the battle of Stamford Bridge in 1066. Orm, the founder of the "minster," is named in Doomsday Book as holding the manor of "Chirchebi," Kirkby, under Hugh Fitzbaldric; this is no doubt Kirkby Moorside in the same neighbourhood, and the manors which included Kirkdale, were also in his tenure.

The dial is in good preservation. It is fortunately protected from the weather by a modern porch, on the face of which another sundial is placed, a simple slab of wood, without a motto.

Orm's younger brother Gamal is mentioned in Doomsday as the holder of Michel-Edstun, or Great Edstone, two miles from Kirkby Moorside, and on this church there is also a Saxon dial. The arrangement of the hour lines is the same as at Kirkdale, and the stone measures 3 feet 11 inches by 1 foot 7 ½ inches. Over the semicircular plane are the remains of the words "OROLOGIVM VIATORIVM," or "wayfarers' time-teller," an inscription which is also found on the drawing of a sun-dial in the Irish MS. Liber St. Isidori, in the library at Bâle.1

1 "Monumental History of the British Church," J. Romilly Allen, S.P.C.K., 1889.

[Full Image]

GREAT EDSTONE.

OLD BYLAND.

On one side of the dial at Great Edstone there is a half-finished inscription:

LOTHAN ME WROHTE A — [Lothan made me.]

Not many miles away, but farther to the north, amongst the Hambleton hills, in the little church of Old Byland, a dial stone was found built upside down into the church porch, with an inscription which for a long time perplexed the antiquaries. At Old Byland a band of Cistercian monks settled themselves in the twelfth century, and when after a few years they removed into the more fertile plains, and built the beautiful abbey which is now in ruins, they called its name Byland, in remembrance of the home they had left. But the dial must have marked time long before the first Cistercian set foot in Ryedale. It is semicircular and divided into ten spaces. Six of the lines are crossed at the end, viz., the fourth, third, and fifth morning hours, and the first and third of the afternoon. The inscription:

+ SVMARLEÐAN HVSCARL ME FECIT. [Sumarlethi's huscarl made me.]

Dr. Haigh considered to be the work of a Dane, and suggested that the decimal time division of the Jutes might have lingered on in Denmark and been brought to Northumbria by the Danish invaders. The name Sumarlethi is an uncommon one, and the title of huscarl (retainer) is not found in English annals before the reign of Cnut. 1

The dial in the south wall of the nave of Aldbrough Church in

1 "Yorks. Arch. Journal," v. ("Yorkshire Dials"), Rev. D. H. Haigh.

[Full Image]

ALDBROUGH.

Holderness is of a different order. It is circular, about 15 ½ inches in diameter, and divided into eight equal parts, with a central hole for the style. In one of the spaces there is a rather elaborate fylfot. The inscription is on the outer circle, and runs thus:

+ VLF HET ÆRIERAN CYRICE FOR HANVM AND FOR GVNWARA SAVLA. [Ulf bade a rear church for poor (or "for himself,") and for Gunwara (her) soul.]

It is not unlikely that this was the Ulf Thoraldsen who gave lands to the minster at York, and whose horn is still preserved amongst its treasures. The inscription is a curious example of a mixed dialect, old English and Scandinavian. Aldbrough Church is chiefly built of pebble, and the arches are pointed, but near the foundations the material is hewn stone, and there are Saxon remains in the chancel.

Dr. Haigh considers that the dial must once have been horizontal, but as it is not the only instance of an early dial inside a church, it is possible that it was so placed originally, and was only intended to catch the rays of the sun at a certain hour on a certain day, perhaps the day of the saint to whom the church was dedicated, or that of Gunwara's death. There is another point worth noting. Anglo-Saxon dials are usually semicircular, this one is completely circular, and exactly resembles those sun-wheels which have been found on stones and relics of the bronze age in Denmark, Ireland, and other parts of Europe, and which are considered to be sun symbols of great antiquity. On the same dial stone we find the fylfot, an Aryan emblem, representing, says Count Goblet d'Alviella, "the sun in its apparent course, the branches being rays in motion." We shall see as we go on that these little wheel dials are frequently found on churches of much later date than Aldbrough. The equal division of the circle into eight parts, though it should indicate the eight tides of the Norsemen, is a useless one for a sun-dial, where the night hours are not needed. Of course a central hole of any depth is conclusive as to the use of part of the stone as a dial, but it does not seem unlikely that the eight-rayed circle may have been a form suggested by the old sun symbol. The fylfot also appears to have been used as a propitiatory symbol with regard to sun and weather. It is often found on church bells which were sounded in times of storm and darkness, as they are still rung during thunder-

[Full Image]

SCHEME OF THE DIAL AT SKELTON, CLEVELAND, WHEN WHOLE.

storms in Italy. In the days of Ulf Thoraldsen sun worship was still a living form of heathenism. The laws of Cnut, who reigned at the beginning of the eleventh century, forbade such heathen worship as that of the sun and moon, springs of water, storms, etc., and without attributing these pagan practices to the founder of Aldbrough Church, the remains of customs and symbols connected with the nature worship which Christianity absorbed and regenerated, are too numerous for us to wonder at the association of the sun-wheel with a Christian church, either in the time of Harold or for many centuries later.1

A few years ago a fragment of another inscribed stone dial was found in the churchyard of Skelton in Cleveland, by Mr. T. M. Fallow. 2 Part of the semicircle remains, and four hour lines, two of which, viz., midday and 2 p.m., are crossed. Apparently the dial had been divided into twelve hour spaces. Below these lines there are portions of four lines of an inscription in Old Norse or Danish, viz.:

|

S . LET NA . GRERA OC . HWA A . COMA. |

with part of a line of runes down the side. "The runes," writes Bishop Browne, "I read as DIEBEL OK, which Mr. Magnusson says is good Danish — of latish date — for 'devil and.' He tells me that

1 "Strange Survivals," S. Baring Gould; "Household Tales," S. O. Addy; "La migration des Symboles," Count Goblet d'Alviella.

2 "The Reliquary," vi. 2, N.S., and "Yorks. Arch. Journal," xlix.

GRERA is part of the word 'to grow,' and COMA is 'to come' or 'they come.' The words 'devil and' may well be a pious curse on creatures of that kind; perhaps a proverbial saying that when the sun is up evil spirits are down."

The thought of the "powers of darkness" is a familiar one to later ages. So too is the prayer:

"And if the night

Have gathered aught of evil, or concealed,

Disperse it, as now light dispels the dark."

From the style of the inscription this stone appears to belong to the early part of the twelfth century.

A small dial built into the wall of the church at Sinnington, in the same Danish district of the North Riding, has but two words left of its inscription: MERGEN, ÆFERN ("morning, evening"). It is divided into eight, and subdivided into sixteen spaces. The like division occurs on a dial at Lockton near Pickering, in the same neighbourhood, cut on the rounded end of a rough block of stone, and now built into the wall of a cottage.

Of three curious little engraved stones at Kirkburn, one, which was merely a ring cross, has apparently been lost during a "restoration." The two which are left are both circular, with half the circle divided, one into ten and the other into twelve spaces.

At Swillington, in the West Riding, a specimen of the decimal division of time was found on a dial built into a fourteenth-century church. It was circular, and, if used as a horizontal dial, had, writes Dr. Haigh, "been designed to show seven equal tenths of day-night, with the spaces below the equinoctial line equally trithed, and to be used in a latitude where the sun rises at 3.36 a.m., which is almost exactly the case at Swillington." Another circular dial (or sun-wheel), about 10 inches in diameter, and with eight divisions, was discovered on a gatepost at Mouse House on Elmley Moor. 1

Besides these there may be mentioned a fragment of an early dial beside one of the windows of the church at Kirkby Moorside, which has suffered much from having been chiselled all over at the restoration of the church, and this shows the division of the day into ten portions. At Marton-cum-Grafton a roughly executed dial, probably old, has been now built into the vestry wall. East Harlsey Church has some rudely-cut lines on the west side of the south door, and Kirkby Grindalyth an irregularly divided dial, and also a curious

1 "Yorks. Arch. Journal," v. ("Yorkshire Dials"), Rev. D. H. Haigh.

double circle, marked by two diagonal lines and with a cross where one of these touches the outer circle. There are also three specimens of dials of different dates on Leake Church, and one at Over Silton near Thirsk; another with eleven hour lines on the church porch at Amotherby, one at Hilton near Stokesley, three on the church at Driffield (one of these is circular, with some very irregular rays), two at Little Driffield, and one at Croft. Dials, probably mediæval, have also been found on the churches of Bulmer and Lastingham. There is a circular one, with lines showing the hours from 5 a.m. to 7 p.m., on the church porch at Kirkby Malzeard. The remains of twenty-four rays can be traced on an old dial in the south wall of Carnaby Church near Bridlington, and on Speeton Church there is also a rude stone which may possibly have once been a dial.

Canon Fowler, in a contribution to the "Yorkshire Archæological Journal," states that he found a great many specimens in Holderness, and also notices the following: "The church of Monk Fryston, near South Milford, has a dial on a stone worked in as a corner stone of the south aisle, and the circle of which is only about 4 1/4 inches in diameter. Burton Agnes Church has two, one somewhat irregularly divided, and the other extending over three stones, telling the hours from 9 a.m. to 7 p.m., and marked by Roman numerals, some of which have disappeared." At Skipsea there is "a very distinctly-marked dial, the radius about a span, the lower half of the circle divided by thirteen radii into twelve spaces, the fourth and seventh line prolonged and with cross bars, apparently to mark 9 a.m. and noon; the 11 a.m. line lengthened, but without a cross bar. At the same church I saw another similarly divided, not so large nor so deeply cut; another smaller still, unequally divided into twelve portions below the horizontal line, and seven above, and there were traces of three others. At Armthorpe near Doncaster there are two dials close together on the face of an ashlar block, one somewhat larger than the other, and the two circles in contact. Each has a central hole for a gnomon, and radiating lines ending in little holes, disposed somewhat irregularly, but apparently meant to indicate twelve or thirteen day hours. These circular dials may be of any date, but are probably mediæval." 1

Another instance of small holes marking the hours is on a dial on the south buttress of the little church at Bolton Castle in Wensleydale. They have evidently been drilled to correct the irregularity of the hour lines. On the fine fourteenth-century church at Kirklington near

1 "Yorks. Arch. Journal," vol. ix.

Bedale there is a nearly obliterated dial on a south buttress, and another is near the priest's door at Burneston Church in the same neighbourhood. This one being cut in a soft sandstone is probably not destined to a long existence. A large dial carved on the church wall at Appleton-le-Wiske, and marked with Roman numerals, may not be more than a couple of centuries old, if so much; and at Harpham Church an east dial cut in the stone shows the hours from 4 to 9 a.m.